# Exploring NIO

Beginning with version 1.4, Java has provided a second I/O system called NIO (which is short for New I/O). It supports a buffer-oriented, channel-based approach to I/O operations. With the release of JDK 7, the NIO system was greatly expanded, providing enhanced support for file-handling and file system features. In fact, so significant were the changes that the term NIO.2 is often used. Because of the capabilities supported by the NIO file classes, NIO has become an important approach to file handling. This chapter explores several of the key features of the NIO system.

# The NIO Classes

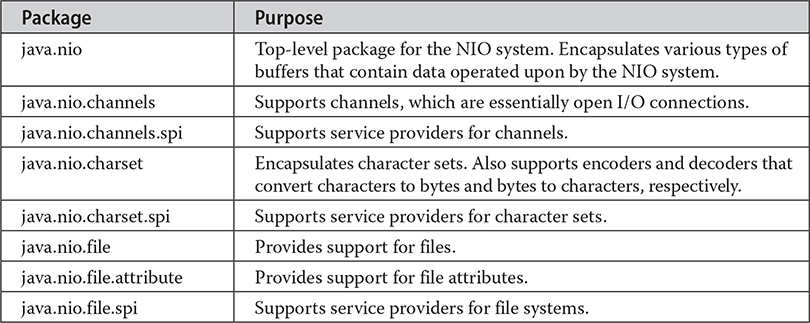

The NIO classes are contained in the packages shown here. Beginning with JDK 9, all are in the java.base module.

Before we begin, it is important to emphasize that the NIO subsystem does not replace the stream-based I/O classes found in java.io, which are discussed in Chapter 22, and good working knowledge of the stream-based I/O in java.io is helpful to understanding NIO.

NOTE This chapter assumes that you have read the overview of I/O given in Chapter 13 and the discussion of stream-based I/O supplied in Chapter 22.

# NIO Fundamentals

The NIO system is built on two foundational items: buffers and channels. A buffer holds data. A channel represents an open connection to an I/O device, such as a file or a socket. In general, to use the NIO system, you obtain a channel to an I/O device and a buffer to hold data. You then operate on the buffer, inputting or outputting data as needed. The following sections examine buffers and channels in more detail.

# Buffers

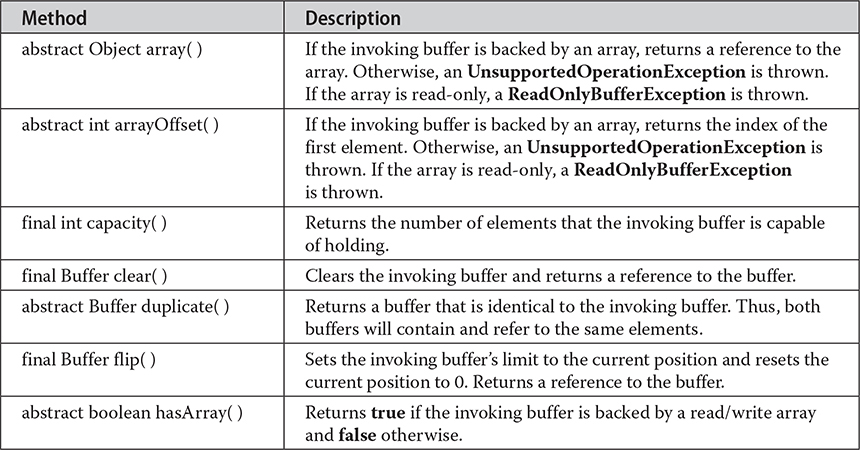

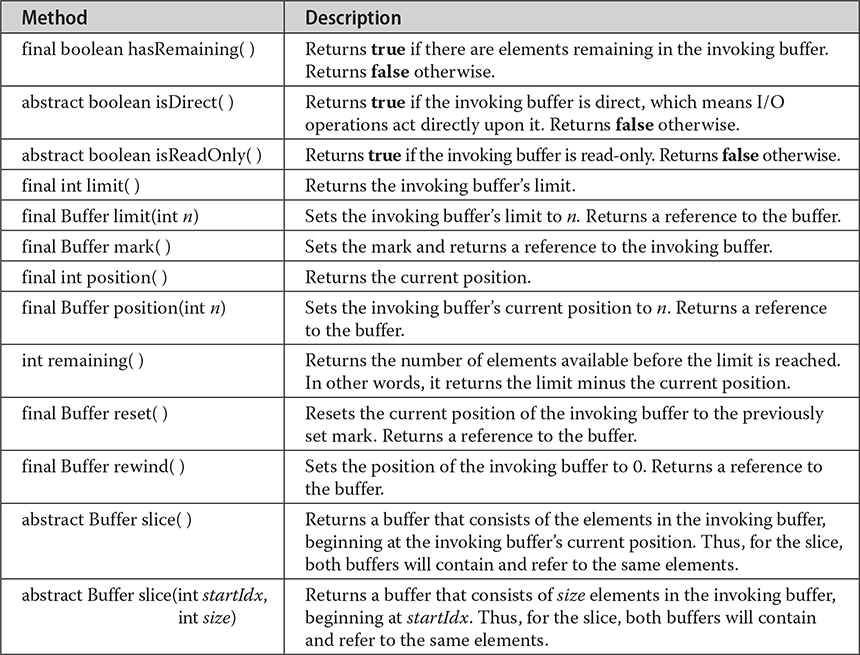

Buffers are defined in the java.nio package. All buffers are subclasses of the Buffer class, which defines the core functionality common to all buffers: current position, limit, and capacity. The current position is the index within the buffer at which the next read or write operation will take place. The current position is advanced by most read or write operations. The limit is the index value one past the last valid location in the buffer. The capacity is the number of elements that the buffer can hold. Often the limit equals the capacity of the buffer. Buffer also supports mark and reset. Buffer defines several methods, which are shown in Table 23-1.

Table 23-1 The Methods Defined by Buffer

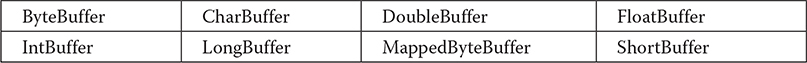

From Buffer, the following specific buffer classes are derived, which hold the type of data that their names imply:

MappedByteBuffer is a subclass of ByteBuffer and is used to map a file to a buffer.

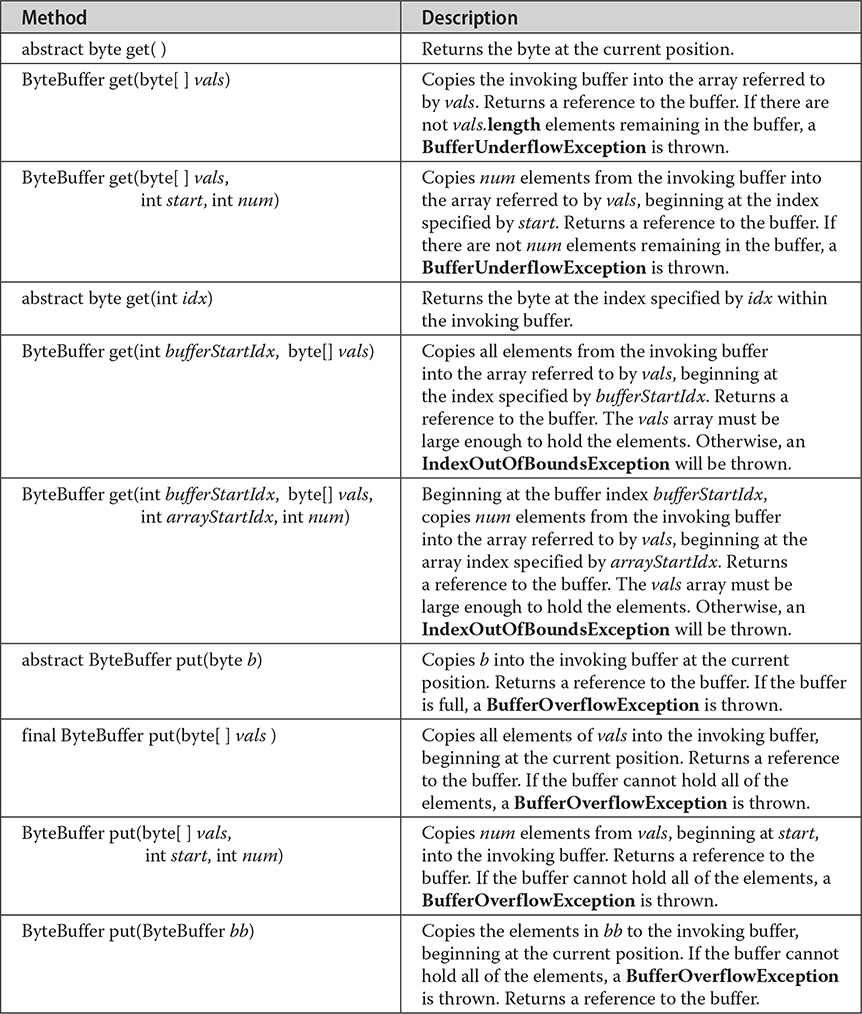

All of the aforementioned buffers provide various get( ) and put( ) methods, which allow you to get data from a buffer or put data into a buffer. (Of course, if a buffer is read-only, then put( ) operations are not available.) Table 23-2 shows the get( ) and put( ) methods defined by ByteBuffer. The other buffer classes have similar methods. All buffer classes also support methods that perform various buffer operations. For example, you can allocate a buffer manually using allocate( ). You can wrap an array inside a buffer using wrap( ). You can create a subsequence of a buffer using slice( ).

Table 23-2 The get( ) and put( ) Methods Defined for ByteBuffer

# Channels

Channels are defined in java.nio.channels. A channel represents an open connection to an I/O source or destination. Channels implement the Channel interface. It extends Closeable, and it extends AutoCloseable. By implementing AutoCloseable, channels can be managed with a try-with-resources statement. When used in a try-with-resources block, a channel is closed automatically when it is no longer needed. (See Chapter 13 for a discussion of try-with-resources.)

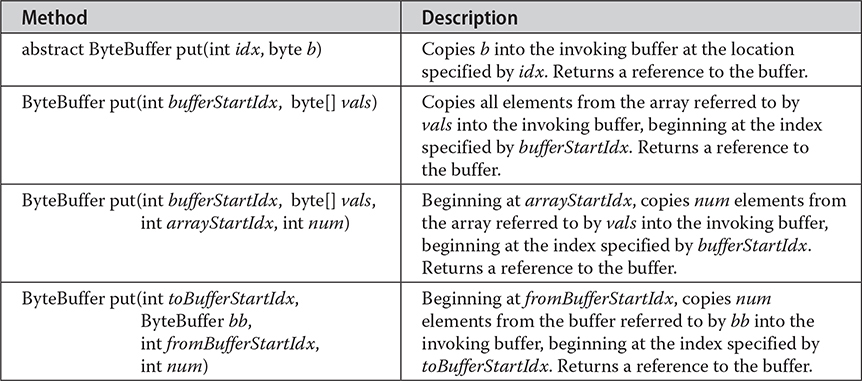

One way to obtain a channel is by calling getChannel( ) on an object that supports channels. For example, getChannel( ) is supported by the following I/O classes:

The specific type of channel returned depends upon the type of object getChannel( ) is called on. For example, when called on a FileInputStream, FileOutputStream, or RandomAccessFile, getChannel( ) returns a channel of type FileChannel. When called on a Socket, getChannel( ) returns a SocketChannel.

Another way to obtain a channel is to use one of the static methods defined by the Files class. For example, using Files, you can obtain a byte channel by calling newByteChannel( ). It returns a SeekableByteChannel, which is an interface implemented by FileChannel. (The Files class is examined in detail later in this chapter.)

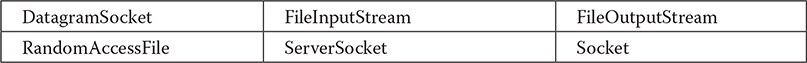

Channels such as FileChannel and SocketChannel support various read( ) and write( ) methods that enable you to perform I/O operations through the channel. For example, here are a few of the read( ) and write( ) methods defined for FileChannel:

All channels support additional methods that give you access to and control over the channel. For example, FileChannel supports methods to get or set the current position, transfer information between file channels, obtain the current size of the channel, and lock the channel, among others. FileChannel provides a static method called open( ), which opens a file and returns a channel to it. This provides another way to obtain a channel. FileChannel also provides the map( ) method, which lets you map a file to a buffer.

# Charsets and Selectors

Two other entities used by NIO are charsets and selectors. A charset defines the way that bytes are mapped to characters. You can encode a sequence of characters into bytes using an encoder. You can decode a sequence of bytes into characters using a decoder. Charsets, encoders, and decoders are supported by classes defined in the java.nio.charset package. Because default encoders and decoders are provided, you will not often need to work explicitly with charsets.

A selector supports key-based, non-blocking, multiplexed I/O. In other words, selectors enable you to perform I/O through multiple channels. Selectors are supported by classes defined in the java.nio.channels package. Selectors are most applicable to socket-backed channels.

We will not use charsets or selectors in this chapter, but you might find them useful in your own applications.

# Enhancements Added by NIO.2

Beginning with JDK 7, the NIO system was substantially expanded and enhanced. In addition to support for the try-with-resources statement (which provides automatic resource management), the improvements included three new packages (java.nio.file, java.nio.file.attribute, and java.nio.file.spi); several new classes, interfaces, and methods; and direct support for stream-based I/O. The additions have greatly expanded the ways in which NIO can be used, especially with files. Several of the key additions are described in the following sections.

# The Path Interface

Perhaps the single most important addition to the NIO system was the Path interface because it encapsulates a path to a file. As you will see, Path is the glue that binds together many of the NIO.2 file-based features. It describes a file’s location within the directory structure. Path is packaged in java.nio.file, and it inherits the following interfaces: Watchable, Iterable<Path>, and Comparable<Path>. Watchable describes an object that can be monitored for changes. The Iterable and Comparable interfaces were described earlier in this book.

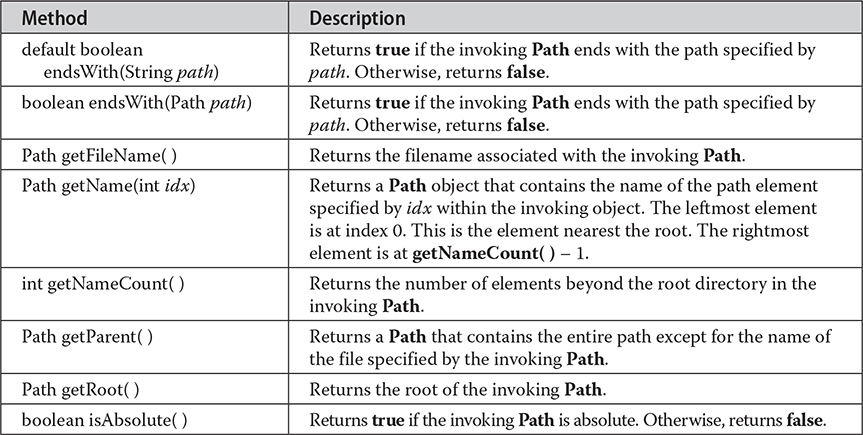

Path declares a number of methods that operate on the path. A sampling is shown in Table 23-3. Pay special attention to the getName( ) method. It is used to obtain an element in a path. It works using an index. At index zero is the part of the path nearest the root, which is the leftmost element in a path. Subsequent indexes specify elements to the right of the root. The number of elements in a path can be obtained by calling getNameCount( ). If you want to obtain a string representation of the entire path, simply call toString( ). Notice that you can resolve a relative path into an absolute path by using the resolve( ) method.

Table 23-3 A Sampling of Methods Specified by Path

Beginning with JDK 11, an important new static factory method called of( ) was added to Path. It returns a Path instance from either a path name or a URI. Thus, of( ) gives you a way to construct a new Path instance.

One other point: When updating legacy code that uses the File class defined by java.io, it is possible to convert a File instance into a Path instance by calling toPath( ) on the File object. Furthermore, it is possible to obtain a File instance by calling the toFile( ) method defined by Path.

# The Files Class

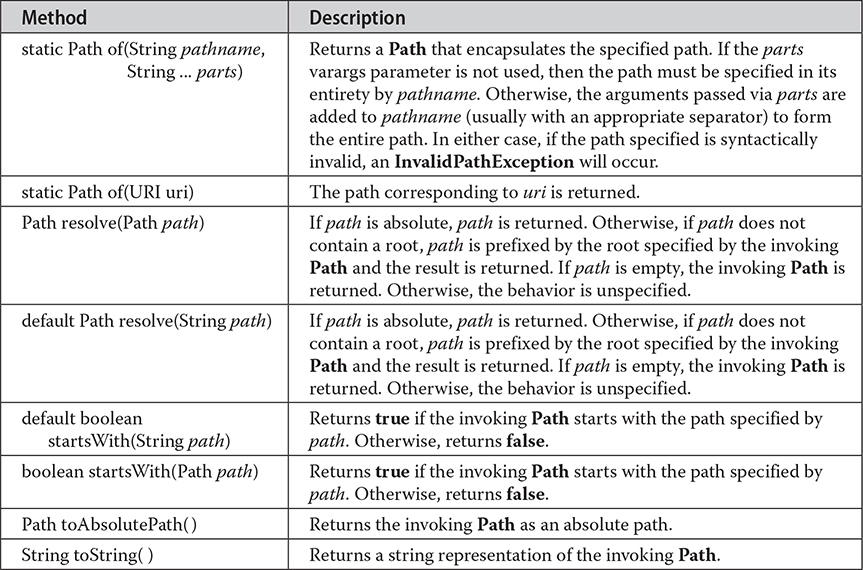

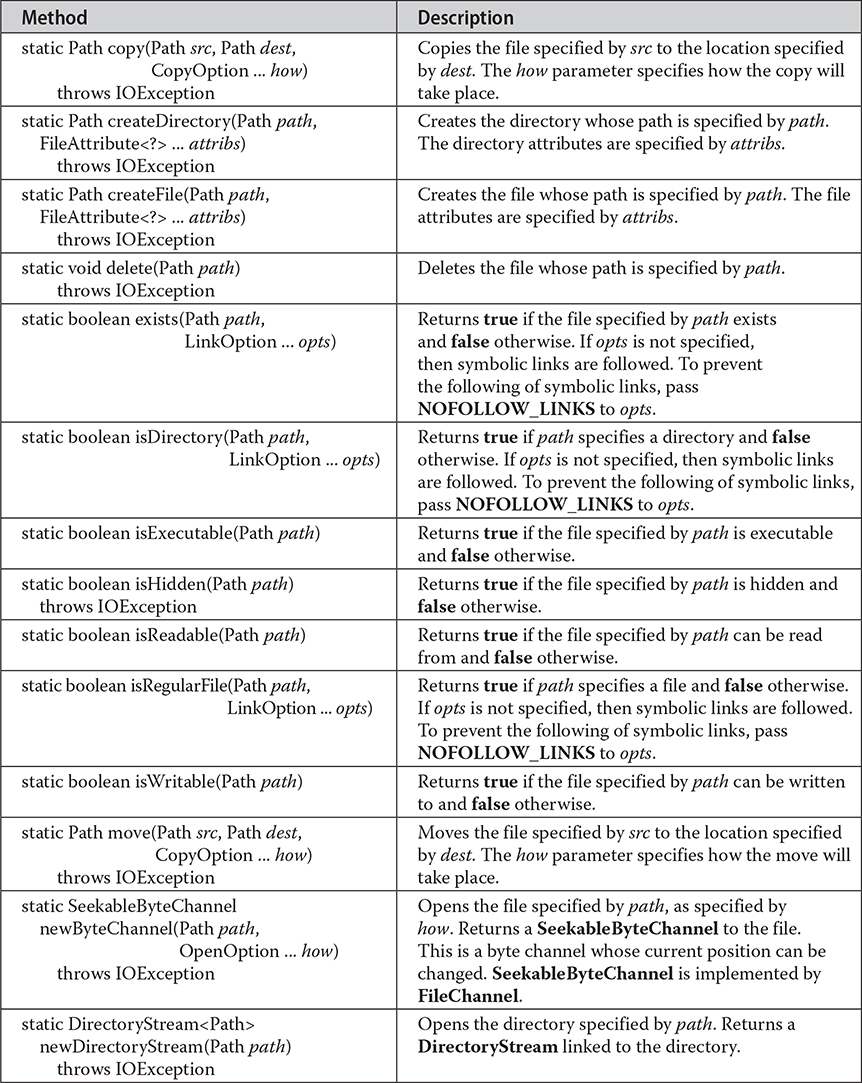

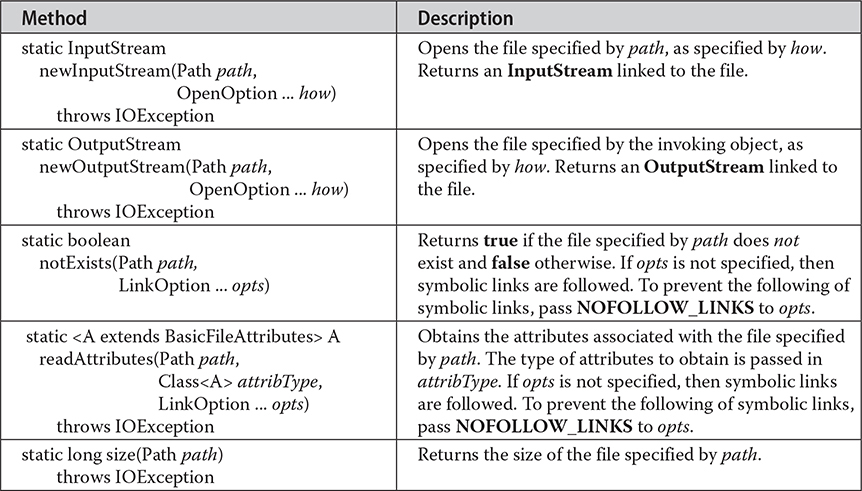

Many of the actions that you perform on a file are provided by static methods within the Files class. The file to be acted upon is specified by its Path. Thus, the Files methods use a Path to specify the file that is being operated upon. Files contains a wide array of functionality. For example, it has methods that let you open or create a file that has the specified path. You can obtain information about a Path, such as whether it is executable, hidden, or read-only. Files also supplies methods that let you copy or move files. A sampling is shown in Table 23-4. In addition to IOException, several other exceptions are possible. Files also includes these four methods: list( ), walk( ), lines( ), and find( ). All return a Stream object. These methods help integrate NIO with the stream API described in Chapter 30. Files also includes the methods readString( ) and writeString( ), which returns a String containing the characters in a file or writes a CharSequence (such as a String) to a file.

Table 23-4 A Sampling of Methods Defined by Files

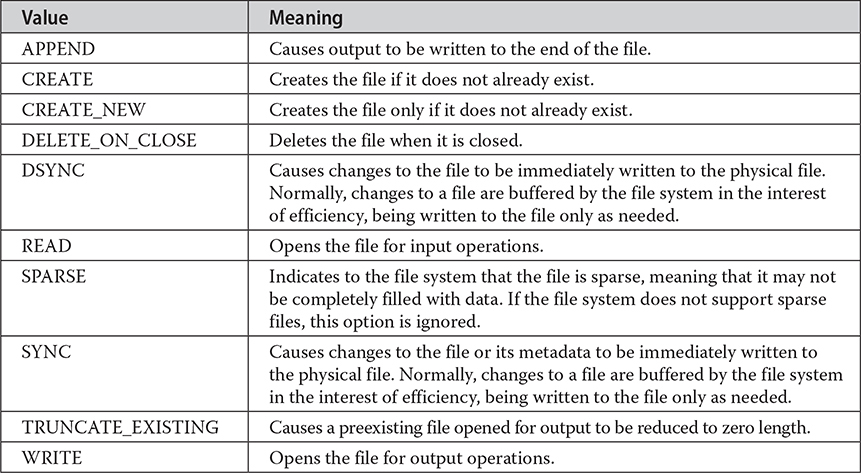

Notice that several of the methods in Table 23-4 take an argument of type OpenOption. This is an interface that describes how to open a file. It is implemented by the StandardOpenOption enumeration that has the values shown in Table 23-5.

Table 23-5 The Standard Open Options

# The Paths Class

Because Path is an interface, not a class, you can’t create an instance of Path directly through the use of a constructor. Instead, you obtain a Path by a calling a method that returns one. Prior to JDK 11, you would typically do this by using the get( ) method defined by the Paths class. There are two forms of get( ). The first is shown here:

static Path get(String pathname, String ... parts)

It returns a Path that encapsulates the specified path. The path can be specified in two ways. First, if parts is not used, then the path must be specified in its entirety by pathname. Alternatively, you can pass the path in pieces, with the first part passed in pathname and the subsequent elements specified by the parts varargs parameter. In either case, if the path specified is syntactically invalid, get( ) will throw an InvalidPathException.

The second form of get( ) creates a Path from a URI. It is shown here:

static Path get(URI uri)

The Path corresponding to uri is returned.

Although the Paths.get( ) method just described has been in use since JDK 7 and, at the time of this writing, is still available for use, it is no longer recommended. Instead, the Java API documentation now recommends the use of the new Path.of( ) method, which was added by JDK 11. Because of this, Path.of( ) is now the preferred approach. Of course, if you are using a compiler that predates JDK 11, then you must continue to use Paths.get( ).

It is important to understand that obtaining a Path to a file does not open or create a file. It simply creates an object that encapsulates the file’s directory path.

# The File Attribute Interfaces

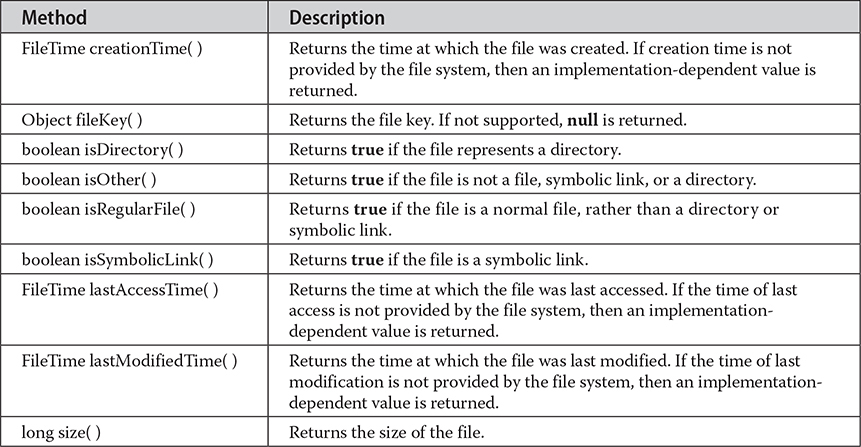

Associated with a file is a set of attributes. These attributes include such things as the file’s time of creation, the time of its last modification, whether the file is a directory, and its size. NIO organizes file attributes into several different interfaces. Attributes are represented by a hierarchy of interfaces defined in java.nio.file.attribute. At the top is BasicFileAttributes. It encapsulates the set of attributes that are commonly found in a variety of file systems. The methods defined by BasicFileAttributes are shown in Table 23-6.

Table 23-6 The Methods Defined by BasicFileAttributes

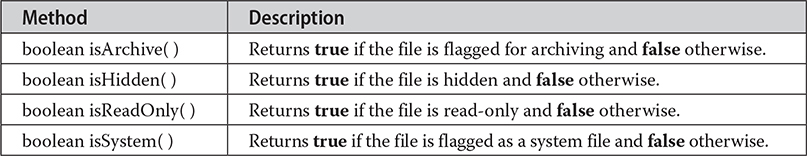

From BasicFileAttributes two interfaces are derived: DosFileAttributes and PosixFileAttributes. DosFileAttributes describes those attributes related to the FAT file system as first defined by DOS. It defines the methods shown here:

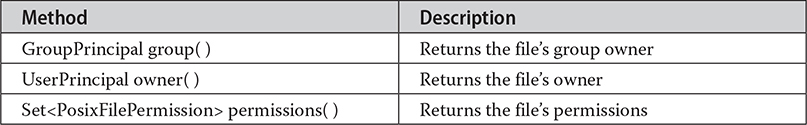

PosixFileAttributes encapsulates attributes defined by the POSIX standards. (POSIX stands for Portable Operating System Interface.) It defines the methods shown here:

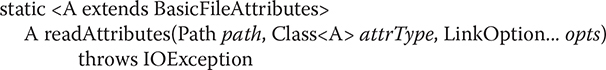

There are various ways to access a file’s attributes. First, you can obtain an object that encapsulates a file’s attributes by calling readAttributes( ), which is a static method defined by Files. One of its forms is shown here:

This method returns a reference to an object that specifies the attributes associated with the file passed in path. The specific type of attributes is specified as a Class object in the attrType parameter. For example, to obtain the basic file attributes, pass BasicFileAttributes.class to attrType. For DOS attributes, use DosFileAttributes.class, and for POSIX attributes, use PosixFileAttributes.class. Optional link options are passed via opts. If not specified, symbolic links are followed. The method returns a reference to requested attributes. If the requested attribute type is not available, UnsupportedOperationException is thrown. Using the object returned, you can access the file’s attributes.

A second way to gain access to a file’s attributes is to call getFileAttributeView( ) defined by Files. NIO defines several attribute view interfaces, including AttributeView, BasicFileAttributeView, DosFileAttributeView, and PosixFileAttributeView, among others. Although we won’t be using attribute views in this chapter, they are a feature that you may find helpful in some situations.

In some cases, you won’t need to use the file attribute interfaces directly because the Files class offers static convenience methods that access several of the attributes. For example, Files includes methods such as isHidden( ) and isWritable( ).

It is important to understand that not all file systems support all possible attributes. For example, the DOS file attributes apply to the older FAT file system as first defined by DOS. The attributes that will apply to a wide variety of file systems are described by BasicFileAttributes. For this reason, these attributes are used in the examples in this chapter.

# The FileSystem, FileSystems, and FileStore Classes

You can easily access the file system through the FileSystem and FileSystems classes packaged in java.nio.file. In fact, by using the newFileSystem( ) method defined by FileSystems, it is even possible to obtain a new file system. The FileStore class encapsulates the file storage system. Although these classes are not used directly in this chapter, you may find them helpful in your own applications.

# Using the NIO System

This section illustrates how to apply the NIO system to a variety of tasks. Before beginning, it is important to emphasize that beginning with JDK 7, the NIO subsystem was greatly expanded. As a result, its uses have also been greatly expanded. As mentioned, the enhanced version is sometimes referred to as NIO.2. Because the features added by NIO.2 are so substantial, they have changed the way that much NIO-based code is written and have increased the types of tasks to which NIO can be applied. Because of its importance, the remaining discussion and examples in this chapter utilize NIO.2 features and, therefore, require a modern version of Java.

In the past, the primary purpose of NIO was channel-based I/O, and this is still a very important use. However, you can now use NIO for stream-based I/O and for performing file-system operations. As a result, the discussion of using NIO is divided into three parts:

• Using NIO for channel-based I/O

• Using NIO for stream-based I/O

• Using NIO for path and file system operations

Because the most common I/O device is the disk file, the rest of this chapter uses disk files in the examples. Because all file channel operations are byte-based, the type of buffers that we will be using are of type ByteBuffer.

Before you can open a file for access via the NIO system, you must obtain a Path that describes the file. In the past, one way to do this was to call the Paths.get( ) factory method. However, as explained earlier, beginning with JDK 11, the preferred approach is to use Path.of( ) rather than Paths.get( ). Because of this, the examples use Path.of( ). If you are using a version of Java prior to JDK 11, simply substitute Paths.get( ) for Path.of( ) in the programs. The form of of( ) used in the examples is shown here:

static Path of(String pathname, String ... parts)

Recall that the path can be specified in two ways. It can be passed in pieces, with the first part passed in pathname and the subsequent elements specified by the parts varargs parameter. Alternatively, the entire path can be specified in pathname and parts is not used. This is the approach used by the examples.

# Use NIO for Channel-Based I/O

An important use of NIO is to access a file via a channel and buffers. The following sections demonstrate some techniques that use a channel to read from and write to a file.

# Reading a File via a Channel

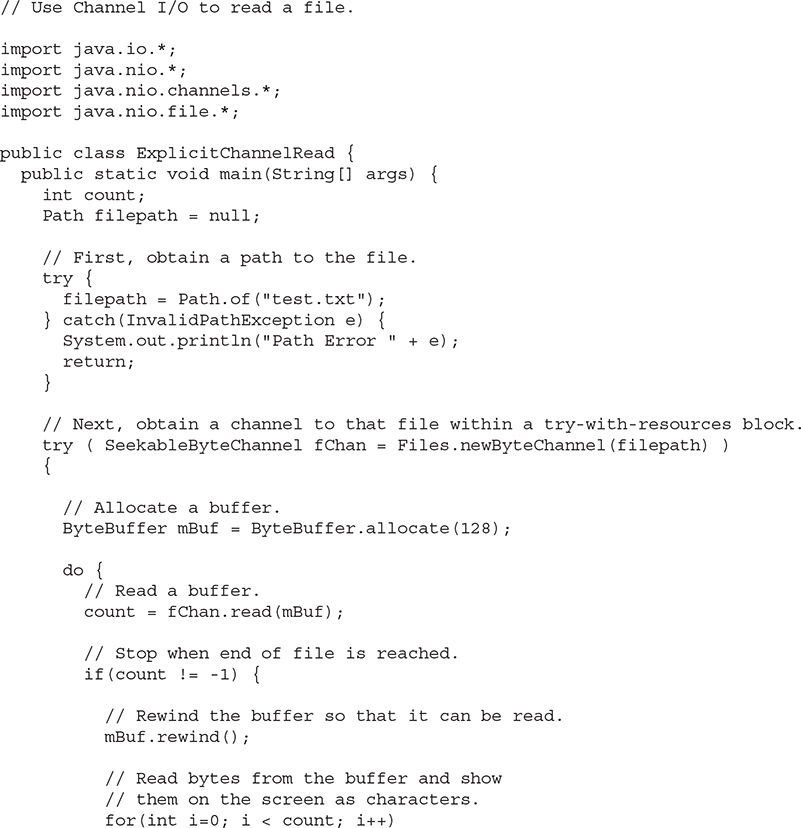

There are several ways to read data from a file using a channel. Perhaps the most common way is to manually allocate a buffer and then perform an explicit read operation that loads that buffer with data from the file. It is with this approach that we begin.

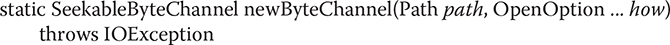

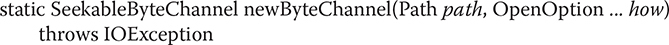

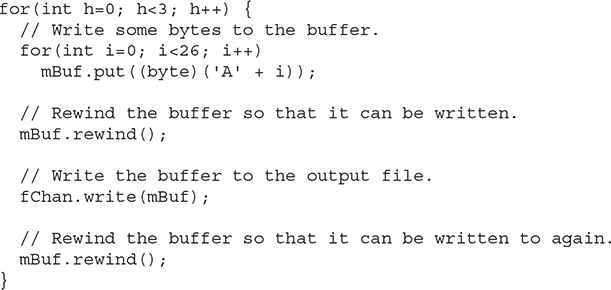

Before you can read from a file, you must open it. To do this, first create a Path that describes the file. Then use this Path to open the file. There are various ways to open the file depending on how it will be used. In this example, the file will be opened for byte-based input via explicit input operations. Therefore, this example will open the file and establish a channel to it by calling Files.newByteChannel( ). The version of newByteChannel( ) that we will use has this general form:

It returns a SeekableByteChannel object, which encapsulates the channel for file operations. The Path that describes the file is passed in path. The how parameter specifies how the file will be opened. Because it is a varargs parameter, you can specify zero or more comma-separated arguments. (The valid values were discussed earlier and shown in Table 23-5.) If no arguments are specified, the file is opened for input operations. SeekableByteChannel is an interface that describes a channel that can be used for file operations. It is implemented by the FileChannel class. When the default file system is used, the returned object can be cast to FileChannel. You must close the channel after you have finished with it. Since all channels, including FileChannel, implement AutoCloseable, you can use a try-with-resources statement to close the file automatically instead of calling close( ) explicitly. This approach is used in the examples.

Next, you must obtain a buffer that will be used by the channel either by wrapping an existing array or by allocating the buffer dynamically. The examples use allocation, but the choice is yours. Because file channels operate on byte buffers, we will use the allocate( ) method defined by ByteBuffer to obtain the buffer. It has this general form:

static ByteBuffer allocate(int cap)

Here, cap specifies the capacity of the buffer. A reference to the buffer is returned.

After you have created the buffer, call read( ) on the channel, passing a reference to the buffer. The version of read( ) that we will use is shown next:

int read(ByteBuffer buf) throws IOException

Each time it is called, read( ) fills the buffer specified by buf with data from the file. The reads are sequential, meaning that each call to read( ) reads the next buffer’s worth of bytes from the file. The read( ) method returns the number of bytes actually read. It returns –1 when there is an attempt to read at the end of the file.

The following program puts the preceding discussion into action by reading a file called test.txt through a channel using explicit input operations:

Here is how the program works. First, a Path object is obtained that contains the relative path to a file called test.txt. A reference to this object is assigned to filepath. Next, a channel connected to the file is obtained by calling newByteChannel( ), passing in filepath. Because no open option is specified, the file is opened for reading. Notice that this channel is the object managed by the try-with-resources statement. Thus, the channel is automatically closed when the block ends. The program then calls the allocate( ) method of ByteBuffer to allocate a buffer that will hold the contents of the file when it is read. A reference to this buffer is stored in mBuf. The contents of the file are then read, one buffer at a time, into mBuf through a call to read( ). The number of bytes read is stored in count. Next, the buffer is rewound through a call to rewind( ). This call is necessary because the current position is at the end of the buffer after the call to read( ). It must be reset to the start of the buffer in order for the bytes in mBuf to be read by calling get( ). (Recall that get( ) is defined by ByteBuffer.) Because mBuf is a byte buffer, the values returned by get( ) are bytes. They are cast to char so the file can be displayed as text. (Alternatively, it is possible to create a buffer that encodes the bytes into characters and then read that buffer.) When the end of the file has been reached, the value returned by read( ) will be –1. When this occurs, the program ends, and the channel is automatically closed.

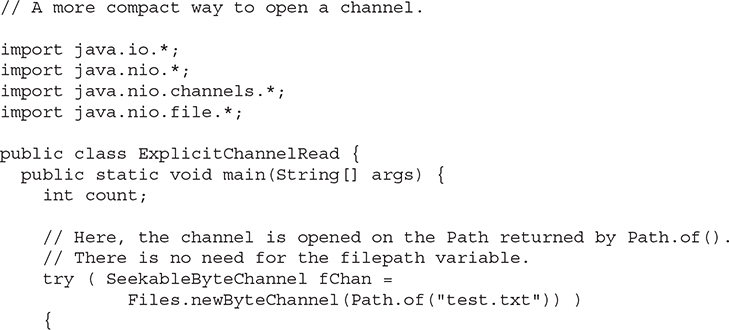

As a point of interest, notice that the program obtains the Path within one try block and then uses another try block to obtain and manage a channel linked to that path. Although there is nothing wrong, per se, with this approach, in many cases, it can be streamlined so that only one try block is needed. In this approach, the calls to Path.of( ) and newByteChannel( ) are sequenced together. For example, here is a reworked version of the program that uses this approach:

In this version, the variable filepath is not needed and both exceptions are handled by the same try statement. Because this approach is more compact, it is the approach used in the rest of the examples in this chapter. Of course, in your own code, you may encounter situations in which the creation of a Path object needs to be separate from the acquisition of a channel. In these cases, the previous approach can be used.

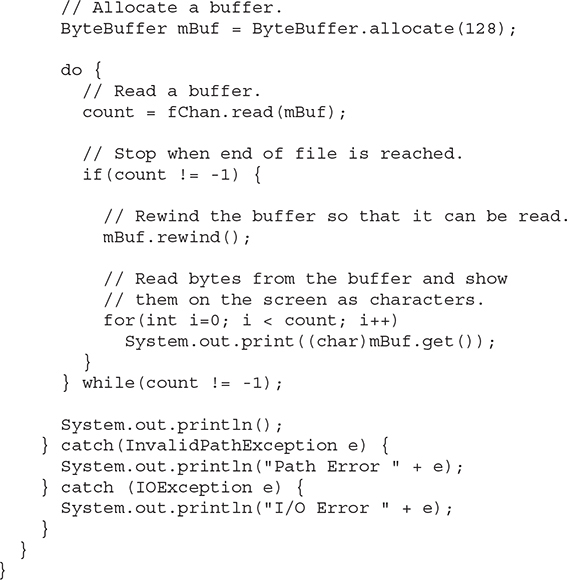

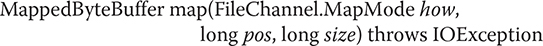

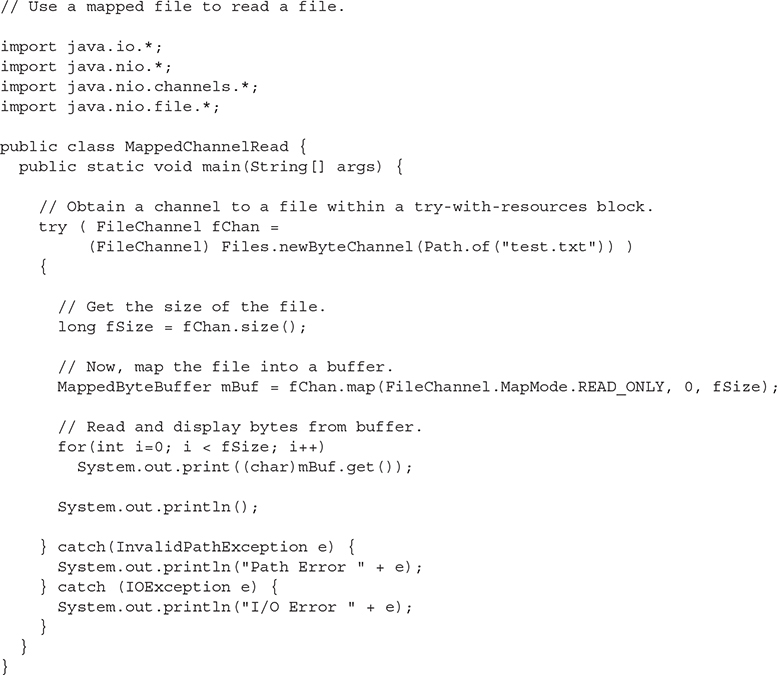

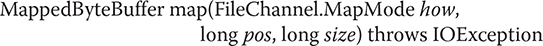

Another way to read a file is to map it to a buffer. The advantage is that the buffer automatically contains the contents of the file. No explicit read operation is necessary. To map and read the contents of a file, follow this general procedure. First, obtain a Path object that encapsulates the file as previously described. Next, obtain a channel to that file by calling Files.newByteChannel( ), passing in the Path and casting the returned object to FileChannel. As explained, newByteChannel( ) returns a SeekableByteChannel. When using the default file system, this object can be cast to FileChannel. Then, map the channel to a buffer by calling map( ) on the channel. The map( ) method is defined by FileChannel. This is why the cast to FileChannel is needed. The map( ) function is shown here:

The map( ) method causes the data in the file to be mapped into a buffer in memory. The value in how determines what type of operations are allowed. It must be one of these values:

For reading a file, use MapMode.READ_ONLY. To read and write, use MapMode.READ_WRITE. MapMode.PRIVATE causes a private copy of the file to be made, and changes to the buffer do not affect the underlying file. The location within the file to begin mapping is specified by pos, and the number of bytes to map are specified by size. A reference to this buffer is returned as a MappedByteBuffer, which is a subclass of ByteBuffer. Once the file has been mapped to a buffer, you can read the file from that buffer. Here is an example that illustrates this approach:

In the program, a Path to the file is created and then opened via newByteChannel( ). The channel is cast to FileChannel and stored in fChan. Next, the size of the file is obtained by calling size( ) on the channel. Then, the entire file is mapped into memory by calling map( ) on fChan and a reference to the buffer is stored in mBuf. Notice that mBuf is declared as a reference to a MappedByteBuffer. The bytes in mBuf are read by calling get( ).

# Writing to a File via a Channel

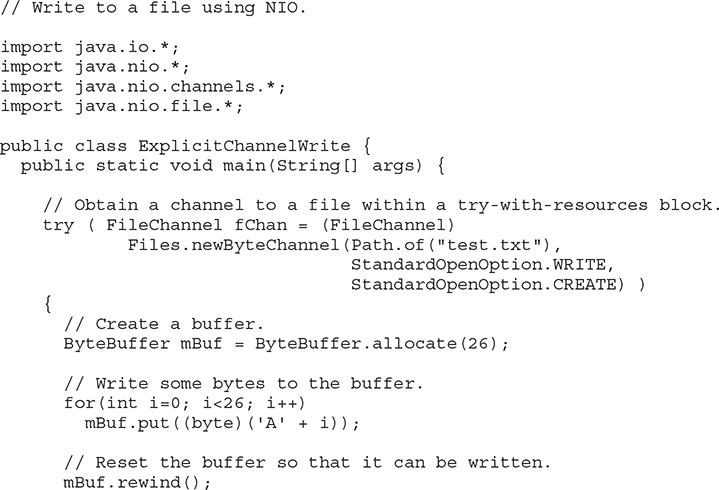

As is the case when reading from a file, there are also several ways to write data to a file using a channel. We will begin with one of the most common. In this approach, you manually allocate a buffer, write data to that buffer, and then perform an explicit write operation to write that data to a file.

Before you can write to a file, you must open it. To do this, first obtain a Path that describes the file and then use this Path to open the file. In this example, the file will be opened for byte-based output via explicit output operations. Therefore, this example will open the file and establish a channel to it by calling Files.newByteChannel( ). As shown in the previous section, the newByteChannel( ) method that we will use has this general form:

It returns a SeekableByteChannel object, which encapsulates the channel for file operations. To open a file for output, the how parameter must specify StandardOpenOption.WRITE. If you want to create the file if it does not already exist, then you must also specify StandardOpenOption.CREATE. (Other options, which are shown in Table 23-5, are also available.) As explained in the previous section, SeekableByteChannel is an interface that describes a channel that can be used for file operations. It is implemented by the FileChannel class. When the default file system is used, the return object can be cast to FileChannel. You must close the channel after you have finished with it.

Here is one way to write to a file through a channel using explicit calls to write( ). First, obtain a Path to the file and then open it with a call to newByteChannel( ), casting the result to FileChannel. Next, allocate a byte buffer and write data to that buffer. Before the data is written to the file, call rewind( ) on the buffer to set its current position to zero. (Each output operation on the buffer increases the current position. Thus, it must be reset prior to writing to the file.) Then, call write( ) on the channel, passing in the buffer. The following program demonstrates this procedure. It writes the alphabet to a file called test.txt.

It is useful to emphasize an important aspect of this program. As mentioned, after data is written to mBuf, but before it is written to the file, a call to rewind( ) on mBuf is made. This is necessary in order to reset the current position to zero after data has been written to mBuf. Remember, each call to put( ) on mBuf advances the current position. Therefore, it is necessary for the current position to be reset to the start of the buffer before calling write( ). If this is not done, write( ) will think that there is no data in the buffer.

Another way to handle the resetting of the buffer between input and output operations is to call flip( ) instead of rewind( ). The flip( ) method sets the value of the current position to zero and the limit to the previous current position. In the preceding example, because the capacity of the buffer equals its limit, flip( ) could have been used instead of rewind( ). However, the two methods are not interchangeable in all cases.

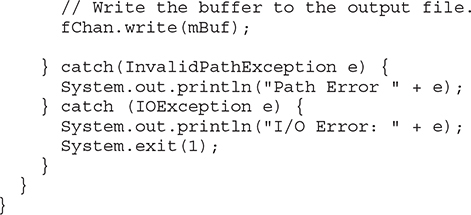

In general, you must reset the buffer between read and write operations. For example, assuming the preceding example, the following loop will write the alphabet to the file three times. Pay special attention to the calls to rewind( ).

Notice that rewind( ) is called between each read and write operation.

One other thing about the program warrants mentioning: When the buffer is written to the file, the first 26 bytes in the file will contain the output. If the file test.txt was preexisting, then after the program executes, the first 26 bytes of test.txt will contain the alphabet, but the remainder of the file will remain unchanged.

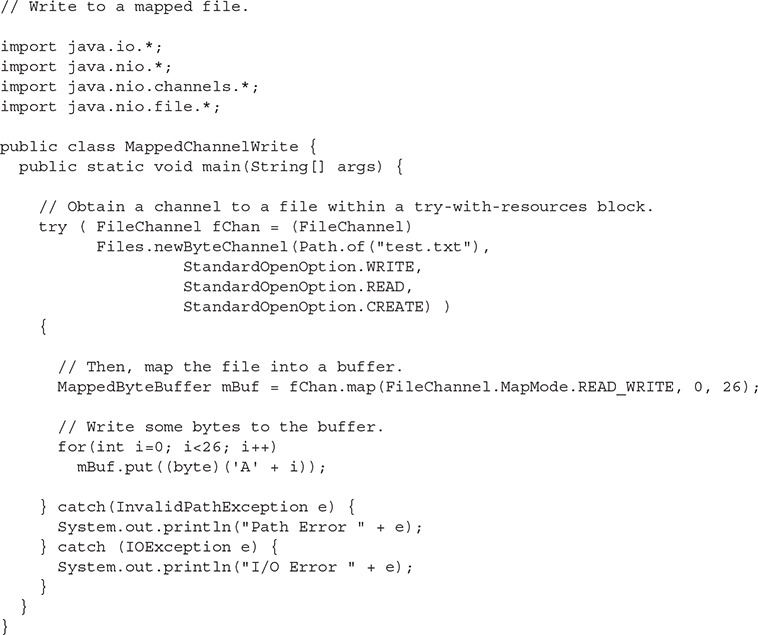

Another way to write to a file is to map it to a buffer. The advantage to this approach is that the data written to the buffer will automatically be written to the file. No explicit write operation is necessary. To map and write the contents of a file, we will use this general procedure. First, obtain a Path object that encapsulates the file and then create a channel to that file by calling Files.newByteChannel( ), passing in the Path. Cast the reference returned by newByteChannel( ) to FileChannel. Next, map the channel to a buffer by calling map( ) on the channel. The map( ) method was described in detail in the previous section. It is summarized here for your convenience. Here is its general form:

The map( ) method causes the data in the file to be mapped into a buffer in memory. The value in how determines what type of operations are allowed. For writing to a file, how must be MapMode.READ_WRITE. The location within the file to begin mapping is specified by pos, and the number of bytes to map are specified by size. A reference to this buffer is returned. Once the file has been mapped to a buffer, you can write data to that buffer, and it will automatically be written to the file. Therefore, no explicit write operations to the channel are necessary.

Here is the preceding program reworked so that a mapped file is used. Notice that in the call to newByteChannel( ), the open option StandardOpenOption.READ has been added. This is because a mapped buffer can either be read-only or read/write. Thus, to write to the mapped buffer, the channel must be opened as read/write.

As you can see, there are no explicit write operations to the channel itself. Because mBuf is mapped to the file, changes to mBuf are automatically reflected in the underlying file.

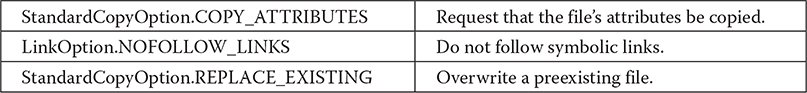

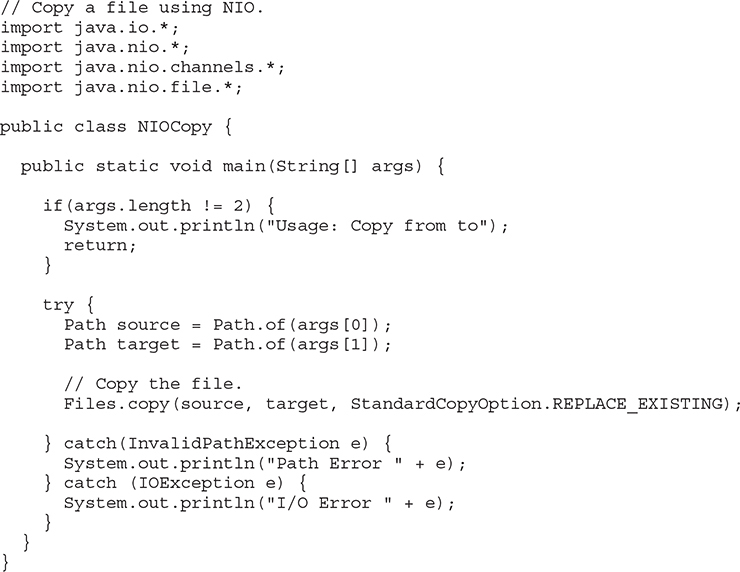

# Copying a File Using NIO

NIO simplifies several types of file operations. Although we can’t examine them all, an example will give you an idea of what is available. The following program copies a file using a call to a single NIO method: copy( ), which is a static method defined by Files. It has several forms. Here is the one we will be using:

static Path copy(Path src, Path dest, CopyOption ... how) throws IOException

The file specified by src is copied to the file specified by dest. How the copy is performed is specified by how. Because it is a varargs parameter, it can be missing. If specified, it can be one or more of these values, which are valid for all file systems:

Other options may be supported, depending on the implementation.

The following program demonstrates copy( ). The source and destination files are specified on the command line, with the source file specified first. Notice how short the program is. You might want to compare this version of the file copy program to the one found in Chapter 13. As you will find, the part of the program that actually copies the file is substantially shorter in the NIO version shown here.

# Use NIO for Stream-Based I/O

Beginning with NIO.2, you can use NIO to open an I/O stream. Once you have a Path, open a file by calling newInputStream( ) or newOutputStream( ), which are static methods defined by Files. These methods return a stream connected to the specified file. In either case, the stream can then be operated on in the way described in Chapter 21, and the same techniques apply. The advantage of using Path to open a file is that all of the features defined by NIO are available for your use.

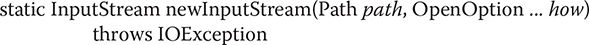

To open a file for stream-based input, use Files.newInputStream( ). It is shown here:

Here, path specifies the file to open and how specifies how the file will be opened. It can be one or more of the values defined by StandardOpenOption, described earlier. (Of course, only those options that relate to an input stream will apply.) If no options are specified, then the file is opened as if StandardOpenOption.READ were passed.

Once opened, you can use any of the methods defined by InputStream. For example, you can use read( ) to read bytes from the file.

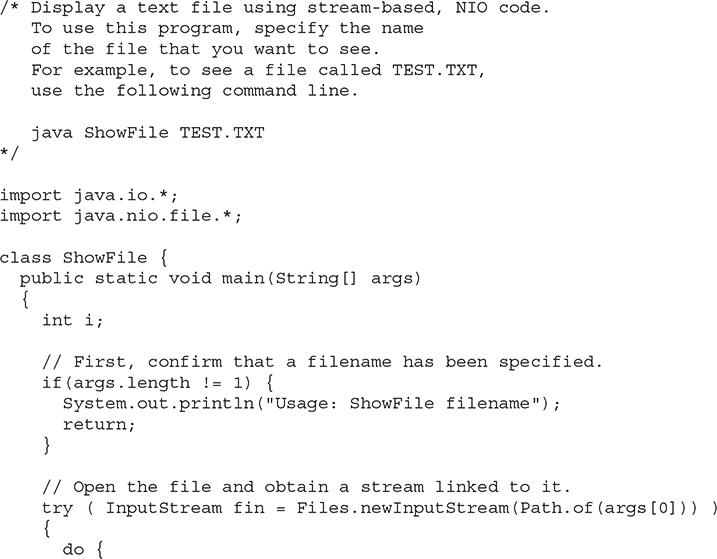

The following program demonstrates the use of NIO-based stream I/O. It reworks the ShowFile program from Chapter 13 so that it uses NIO features to open the file and obtain a stream. As you can see, it is very similar to the original, except for the use of Path and newInputStream( ).

Because the stream returned by newInputStream( ) is a normal stream, it can be used like any other stream. For example, you can wrap the stream inside a buffered stream, such as a BufferedInputStream, to provide buffering, as shown here:

new BufferedInputStream(Files.newInputStream(Path.of(args[0])))

Now, all reads will be automatically buffered.

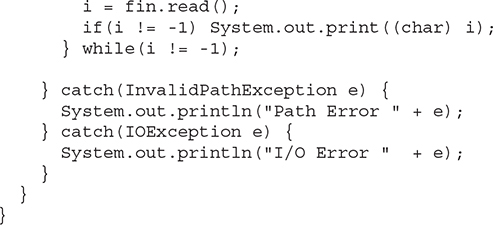

To open a file for output, use Files.newOutputStream( ). It is shown here:

Here, path specifies the file to open and how specifies how the file will be opened. It must be one or more of the values defined by StandardOpenOption, described earlier. (Of course, only those options that relate to an output stream will apply.) If no options are specified, then the file is opened as if StandardOpenOption.WRITE, StandardOpenOption.CREATE, and StandardOpenOption.TRUNCATE_EXISTING were passed.

The methodology for using newOutputStream( ) is similar to that shown previously for newInputStream( ). Once opened, you can use any of the methods defined by OutputStream. For example, you can use write( ) to write bytes to the file. You can also wrap the stream inside a BufferedOutputStream to buffer the stream.

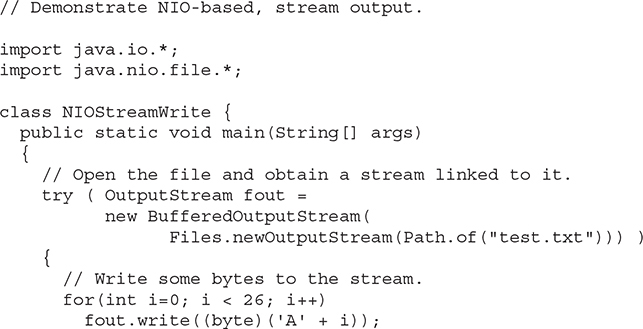

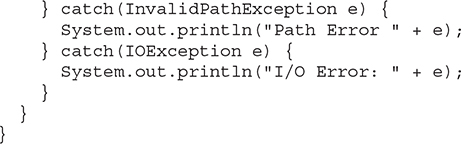

The following program shows newOutputStream( ) in action. It writes the alphabet to a file called test.txt. Notice the use of buffered I/O.

# Use NIO for Path and File System Operations

At the beginning of Chapter 22, the File class in the java.io package was examined. As explained there, the File class deals with the file system and with the various attributes associated with a file, such as whether a file is read-only, hidden, and so on. It was also used to obtain information about a file’s path. Although the File class is still perfectly acceptable, the interfaces and classes defined by NIO.2 offer a better way to perform these functions. The benefits include support for symbolic links, better support for directory tree traversal, and improved handling of metadata, among others. The following sections show samples of two common file system operations: obtaining information about a path and file and getting the contents of a directory.

REMEMBER If you want to change code that uses java.io.File to the Path interface, you can use the toPath( ) method to obtain a Path instance from a File instance.

# Obtain Information About a Path and a File

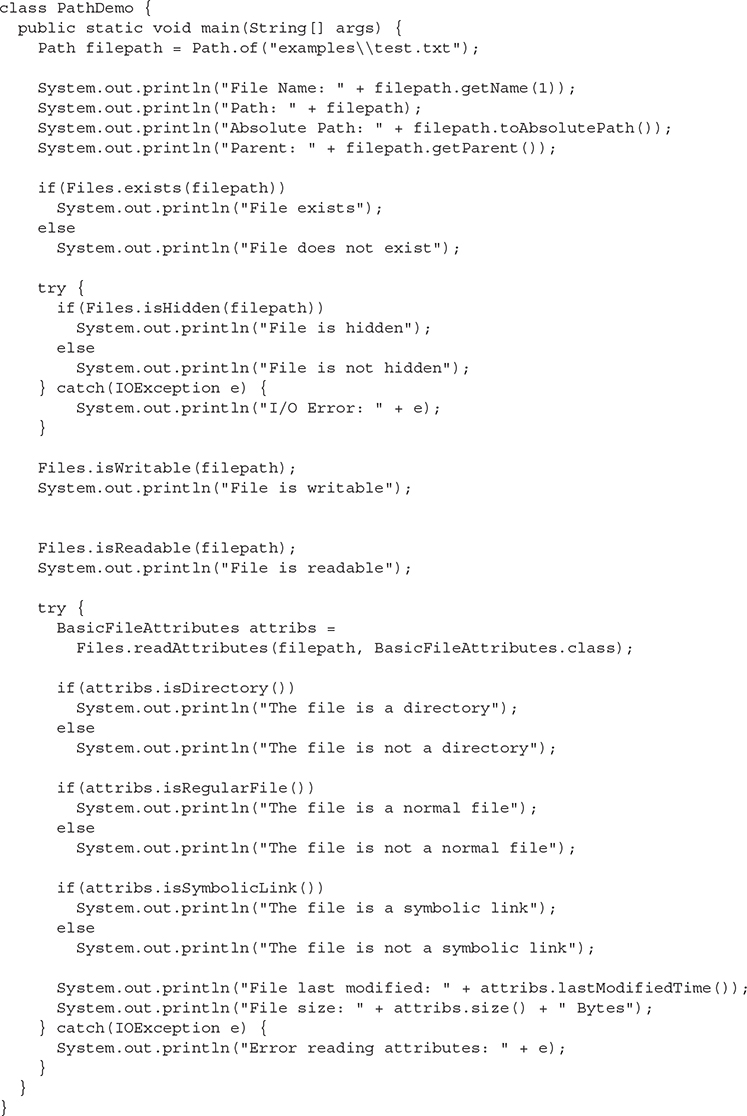

Information about a path can be obtained by using methods defined by Path. Some attributes associated with the file described by a Path (such as whether or not the file is hidden) are obtained by using methods defined by Files. The Path methods used here are getName( ), getParent( ), and toAbsolutePath( ). Those provided by Files are isExecutable( ), isHidden( ), isReadable( ), isWritable( ), and exists( ). These are summarized in Tables 23-3 and 23-4, shown earlier.

CAUTION Methods such as isExecutable( ), isReadable( ), isWritable( ), and exists( ) must be used with care because the state of the file system may change after the call, in which case a program malfunction could occur. Such a situation could have security implications.

Other file attributes are obtained by requesting a list of attributes by calling Files.readAttributes( ). In the program, this method is called to obtain the BasicFileAttributes associated with a file, but the general approach applies to other types of attributes.

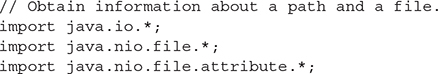

The following program demonstrates several of the Path and Files methods, along with several methods provided by BasicFileAttributes. This program assumes that a file called test.txt exists in a directory called examples, which must be a subdirectory of the current directory.

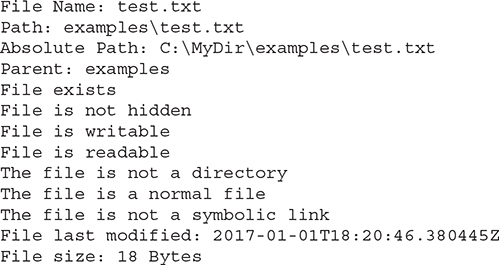

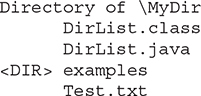

If you execute this program from a directory called MyDir, which has a subdirectory called examples, and the examples directory contains the test.txt file, then you will see output similar to that shown here. (Of course, the information you see will differ.)

If you are using a computer that supports the FAT file system (i.e., the DOS file system), then you might want to try using the methods defined by DosFileAttributes. If you are using a POSIX-compatible system, then try using PosixFileAttributes.

# List the Contents of a Directory

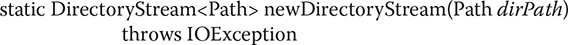

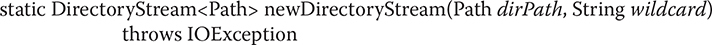

If a path describes a directory, then you can read the contents of that directory by using static methods defined by Files. To do this, you first obtain a directory stream by calling newDirectoryStream( ), passing in a Path that describes the directory. One form of newDirectoryStream( ) is shown here:

Here, dirPath encapsulates the path to the directory. The method returns a DirectoryStream<Path> object that can be used to obtain the contents of the directory. It will throw an IOException if an I/O error occurs and a NotDirectoryException (which is a subclass of IOException) if the specified path is not a directory. A SecurityException is also possible if access to the directory is not permitted.

DirectoryStream<Path> implements AutoCloseable, so it can be managed by a try-with-resources statement. It also implements Iterable<Path>. This means that you can obtain the contents of the directory by iterating over the DirectoryStream object. When iterating, each directory entry is represented by a Path instance. An easy way to iterate over a DirectoryStream is to use a for-each style for loop. It is important to understand, however, that the iterator implemented by DirectoryStream<Path> can be obtained only once for each instance. Thus, the iterator( ) method can be called only once, and a for-each loop can be executed only once.

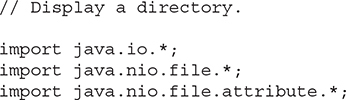

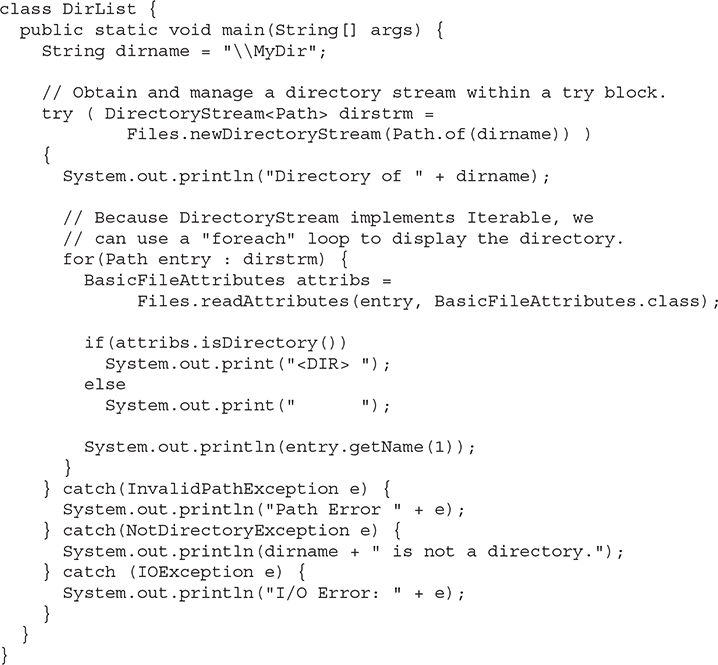

The following program displays the contents of a directory called MyDir:

Here is sample output from the program:

You can filter the contents of a directory in two ways. The easiest is to use this version of newDirectoryStream( ):

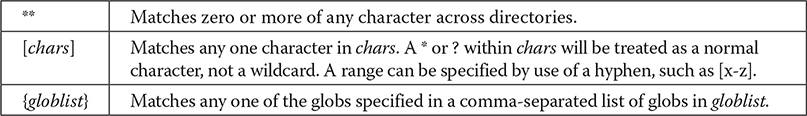

In this version, only files that match the wildcard filename specified by wildcard will be obtained. For wildcard, you can specify either a complete filename or a glob. A glob is a string that defines a general pattern that will match one or more files using the familiar * and ? wildcard characters. These match zero or more of any character and any one character, respectively. The following are also recognized within a glob:

You can specify a * or ? character using \* and \?. To specify a \, use \\. You can experiment with a glob by substituting this call to newDirectoryStream( ) into the previous program:

Files.newDirectoryStream(Path.of(dirname), "{Path,Dir}*.{java,class}")

This obtains a directory stream that contains only those files whose names begin with either "Path" or "Dir" and use either the "java" or "class" extension. Thus, it would match names like DirList.java and PathDemo.java, but not MyPathDemo.java, for example.

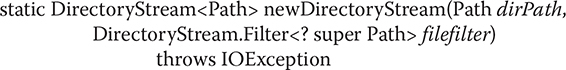

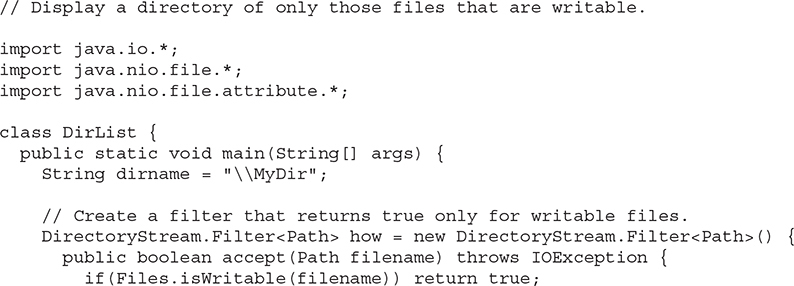

Another way to filter a directory is to use this version of newDirectoryStream( ):

Here, DirectoryStream.Filter is an interface that specifies the following method:

boolean accept(T entry) throws IOException

In this case, T will be Path. If you want to include entry in the list, return true. Otherwise, return false. This form of newDirectoryStream( ) offers the advantage of being able to filter a directory based on something other than a filename. For example, you can filter based on size, creation date, modification date, or attribute, to name a few.

The following program demonstrates the process. It will list only those files that are writable.

# Use walkFileTree( ) to List a Directory Tree

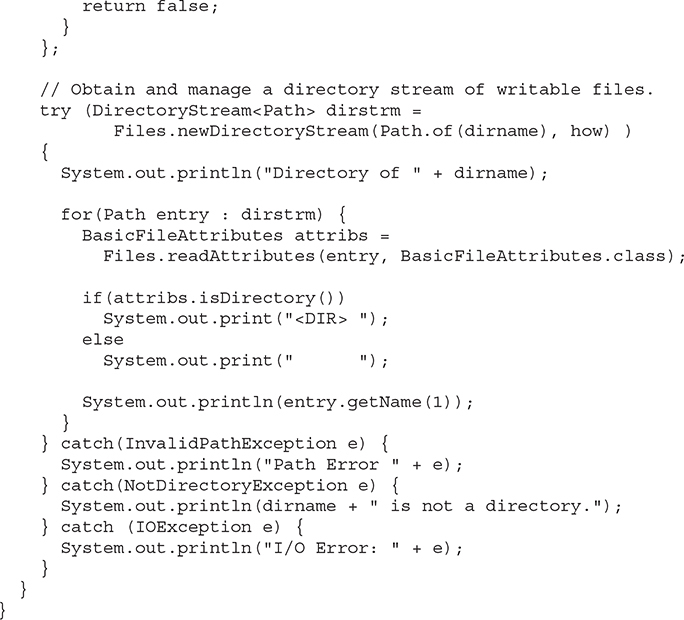

The preceding examples have obtained the contents of only a single directory. However, sometimes you will want to obtain a list of the files in a directory tree. In the past, this was quite a chore, but NIO.2 makes it easy because now you can use the walkFileTree( ) method defined by Files to process a directory tree. It has two forms. The one used in this chapter is shown here:

The path to the starting point of the directory walk is passed in root. An instance of FileVisitor is passed in fv. The implementation of FileVisitor determines how the directory tree is traversed, and it gives you access to the directory information. If an I/O error occurs, an IOException is thrown. A SecurityException is also possible.

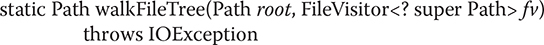

FileVisitor is an interface that defines how files are visited when a directory tree is traversed. It is a generic interface that is declared like this:

interface FileVisitor<T>

For use in walkFileTree( ), T will be Path (or any type derived from Path). FileVisitor defines the following methods:

Notice that each method returns a FileVisitResult. This enumeration defines the following values:

In general, to continue traversing the directory and subdirectories, a method should return CONTINUE. For preVisitDirectory( ), return SKIP_SIBLINGS to bypass the directory and its siblings and prevent postVisitDirectory( ) from being called. To bypass just the directory and subdirectories, return SKIP_SUBTREE. To stop the directory traversal, return TERMINATE.

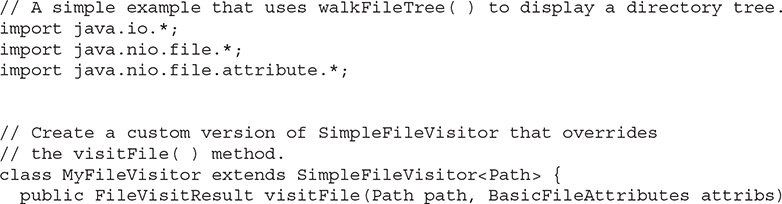

Although it is certainly possible to create your own visitor class that implements these methods defined by FileVisitor, you won’t normally do so because a simple implementation is provided by SimpleFileVisitor. You can just override the default implementation of the method or methods in which you are interested. Here is a short example that illustrates the process. It displays all files in the directory tree that has \MyDir as its root. Notice how short this program is.

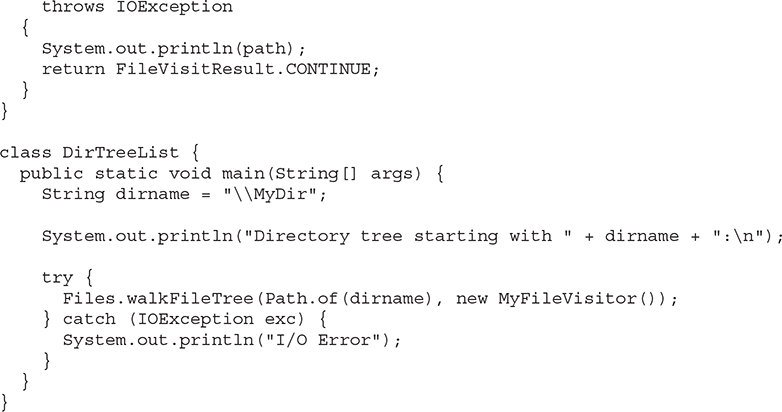

Here is sample output produced by the program when used on the same MyDir directory shown earlier. In this example, the subdirectory called examples contains one file called MyProgram.java.

In the program, the class MyFileVisitor extends SimpleFileVisitor, overriding only the visitFile( ) method. In this example, visitFile( ) simply displays the files, but more sophisticated functionality is easy to achieve. For example, you could filter the files or perform actions on the files, such as copying them to a backup device. For the sake of clarity, a named class was used to override visitFile( ), but you could also use an anonymous inner class.

One last point: It is possible to watch a directory for changes by using java.nio.file.WatchService.