# Generics

Since the original 1.0 release in 1995, many new features have been added to Java. One that has had a profound and long-lasting impact is generics. Introduced by JDK 5, generics changed Java in two important ways. First, they added a new syntactical element to the language. Second, they caused changes to many of the classes and methods in the core API. Today, generics are an integral part of Java programming, and a solid understanding of this important feature is required. It is examined here in detail.

Through the use of generics, it is possible to create classes, interfaces, and methods that will work in a type-safe manner with various kinds of data. Many algorithms are logically the same no matter what type of data they are being applied to. For example, the mechanism that supports a stack is the same whether that stack is storing items of type Integer, String, Object, or Thread. With generics, you can define an algorithm once, independently of any specific type of data, and then apply that algorithm to a wide variety of data types without any additional effort. The expressive power generics added to the language fundamentally changed the way that Java code is written.

Perhaps the one feature of Java that was most significantly affected by generics is the Collections Framework. The Collections Framework is part of the Java API and is described in detail in Chapter 20, but a brief mention is useful now. A collection is a group of objects. The Collections Framework defines several classes, such as lists and maps, that manage collections. The collection classes had always been able to work with any type of object. The benefit that generics added is the ability to use the collection classes with complete type safety. Thus, in addition to being a powerful language element on its own, generics also enabled an existing feature to be substantially improved. This is another reason why generics were such an important addition to Java.

This chapter describes the syntax, theory, and use of generics. It also shows how generics provide type safety for some previously difficult cases. Once you have completed this chapter, you will want to examine Chapter 20, which covers the Collections Framework. There you will find many examples of generics at work.

# What Are Generics?

At its core, the term generics means parameterized types. Parameterized types are important because they enable you to create classes, interfaces, and methods in which the type of data upon which they operate is specified as a parameter. Using generics, it is possible to create a single class, for example, that automatically works with different types of data. A class, interface, or method that operates on a parameterized type is called generic, as in generic class or generic method.

It is important to understand that Java has always given you the ability to create generalized classes, interfaces, and methods by operating through references of type Object. Because Object is the superclass of all other classes, an Object reference can refer to any type object. Thus, in pre-generics code, generalized classes, interfaces, and methods used Object references to operate on various types of objects. The problem was that they could not do so with type safety.

Generics added the type safety that was lacking. They also streamlined the process, because it is no longer necessary to explicitly employ casts to translate between Object and the type of data that is actually being operated upon. With generics, all casts are automatic and implicit. Thus, generics expanded your ability to reuse code and let you do so safely and easily.

CAUTION A Warning to C++ Programmers: Although generics are similar to templates in C++, they are not the same. There are some fundamental differences between the two approaches to generic types. If you have a background in C++, it is important not to jump to conclusions about how generics work in Java.

# A Simple Generics Example

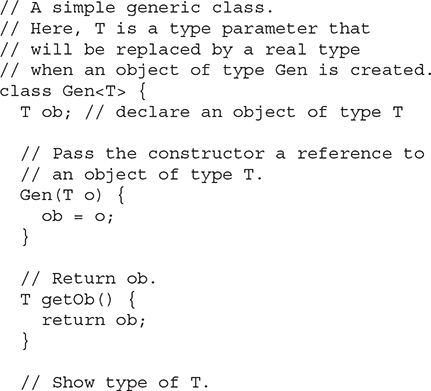

Let’s begin with a simple example of a generic class. The following program defines two classes. The first is the generic class Gen, and the second is GenDemo, which uses Gen.

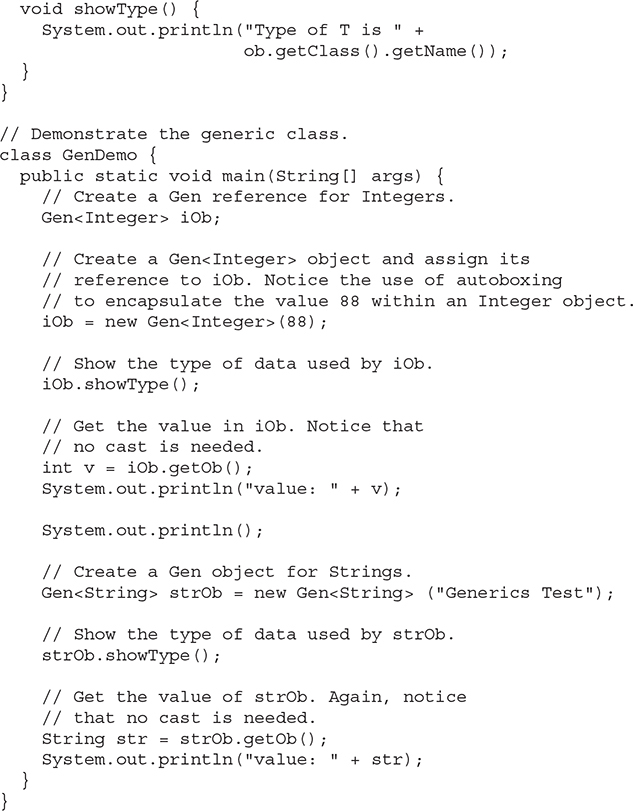

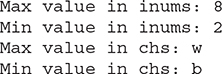

The output produced by the program is shown here:

Let’s examine this program carefully.

First, notice how Gen is declared by the following line:

class Gen\<T\> {

Here, T is the name of a type parameter. This name is used as a placeholder for the actual type that will be passed to Gen when an object is created. Thus, T is used within Gen whenever the type parameter is needed. Notice that T is contained within < >. This syntax can be generalized. Whenever a type parameter is being declared, it is specified within angle brackets. Because Gen uses a type parameter, Gen is a generic class, which is also called a parameterized type.

In the declaration of Gen, there is no special significance to the name T. Any valid identifier could have been used, but T is traditional. Furthermore, it is recommended that type parameter names be single-character capital letters. Other commonly used type parameter names are V and E. One other point about type parameter names: Beginning with JDK 10, you cannot use var as the name of a type parameter.

Next, T is used to declare an object called ob, as shown here:

T ob; // declare an object of type T

As explained, T is a placeholder for the actual type that will be specified when a Gen object is created. Thus, ob will be an object of the type passed to T. For example, if type String is passed to T, then in that instance, ob will be of type String.

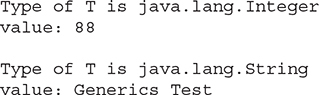

Now consider Gen’s constructor:

Notice that its parameter, o, is of type T. This means that the actual type of o is determined by the type passed to T when a Gen object is created. Also, because both the parameter o and the member variable ob are of type T, they will both be of the same actual type when a Gen object is created.

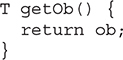

The type parameter T can also be used to specify the return type of a method, as is the case with the getOb( ) method, shown here:

Because ob is also of type T, its type is compatible with the return type specified by getOb( ).

The showType( ) method displays the type of T by calling getName( ) on the Class object returned by the call to getClass( ) on ob. The getClass( ) method is defined by Object and is thus a member of all class types. It returns a Class object that corresponds to the type of the class of the object on which it is called. Class defines the getName( ) method, which returns a string representation of the class name.

The GenDemo class demonstrates the generic Gen class. It first creates a version of Gen for integers, as shown here:

Gen\<Integer\> iOb;

Look closely at this declaration. First, notice that the type Integer is specified within the angle brackets after Gen. In this case, Integer is a type argument that is passed to Gen’s type parameter, T. This effectively creates a version of Gen in which all references to T are translated into references to Integer. Thus, for this declaration, ob is of type Integer, and the return type of getOb( ) is of type Integer.

Before moving on, it’s necessary to state that the Java compiler does not actually create different versions of Gen, or of any other generic class. Although it’s helpful to think in these terms, it is not what actually happens. Instead, the compiler removes all generic type information, substituting the necessary casts, to make your code behave as if a specific version of Gen were created. Thus, there is really only one version of Gen that actually exists in your program. The process of removing generic type information is called erasure, and we will return to this topic later in this chapter.

The next line assigns to iOb a reference to an instance of an Integer version of the Gen class:

iOb = new Gen\<Integer\>(88);

Notice that when the Gen constructor is called, the type argument Integer is also specified. This is because the type of the object (in this case iOb) to which the reference is being assigned is of type Gen<Integer>. Thus, the reference returned by new must also be of type Gen<Integer>. If it isn’t, a compile-time error will result. For example, the following assignment will cause a compile-time error:

iOb = new Gen\<Double\>(88.0); // Error!

Because iOb is of type Gen<Integer>, it can’t be used to refer to an object of Gen<Double>. This type checking is one of the main benefits of generics because it ensures type safety.

NOTE As you will see later in this chapter, it is possible to shorten the syntax used to create an instance of a generic class. In the interest of clarity, we will use the full syntax at this time.

As the comments in the program state, the assignment

iOb = new Gen\<Integer\>(88);

makes use of autoboxing to encapsulate the value 88, which is an int, into an Integer. This works because Gen<Integer> creates a constructor that takes an Integer argument. Because an Integer is expected, Java will automatically box 88 inside one. Of course, the assignment could also have been written explicitly, like this:

iOb = new Gen\<Integer\>(Integer.valueOf(88));

However, there would be no benefit to using this version.

The program then displays the type of ob within iOb, which is Integer. Next, the program obtains the value of ob by use of the following line:

int v = iOb.getOb();

Because the return type of getOb( ) is T, which was replaced by Integer when iOb was declared, the return type of getOb( ) is also Integer, which unboxes into int when assigned to v (which is an int). Thus, there is no need to cast the return type of getOb( ) to Integer. Of course, it’s not necessary to use the auto-unboxing feature. The preceding line could have been written like this, too:

int v = iOb.getOb().intValue();

However, the auto-unboxing feature makes the code more compact.

Next, GenDemo declares an object of type Gen<String>:

Gen\<String\> strOb = new Gen\<String\>("Generics Test");

Because the type argument is String, String is substituted for T inside Gen. This creates (conceptually) a String version of Gen, as the remaining lines in the program demonstrate.

# Generics Work Only with Reference Types

When declaring an instance of a generic type, the type argument passed to the type parameter must be a reference type. You cannot use a primitive type, such as int or char. For example, with Gen, it is possible to pass any class type to T, but you cannot pass a primitive type to a type parameter. Therefore, the following declaration is illegal:

Gen\<int\> intOb = new Gen\<int\>(53); // Error, can't use primitive type

Of course, not being able to specify a primitive type is not a serious restriction because you can use the type wrappers (as the preceding example did) to encapsulate a primitive type. Further, Java’s autoboxing and auto-unboxing mechanism makes the use of the type wrapper transparent.

# Generic Types Differ Based on Their Type Arguments

A key point to understand about generic types is that a reference of one specific version of a generic type is not type compatible with another version of the same generic type. For example, assuming the program just shown, the following line of code is in error and will not compile:

iOb = strOb; // Wrong!

Even though both iOb and strOb are of type Gen<T>, they are references to different types because their type arguments differ. This is part of the way that generics add type safety and prevent errors.

# How Generics Improve Type Safety

At this point, you might be asking yourself the following question: Given that the same functionality found in the generic Gen class can be achieved without generics, by simply specifying Object as the data type and employing the proper casts, what is the benefit of making Gen generic? The answer is that generics automatically ensure the type safety of all operations involving Gen. In the process, they eliminate the need for you to enter casts and to type-check code by hand.

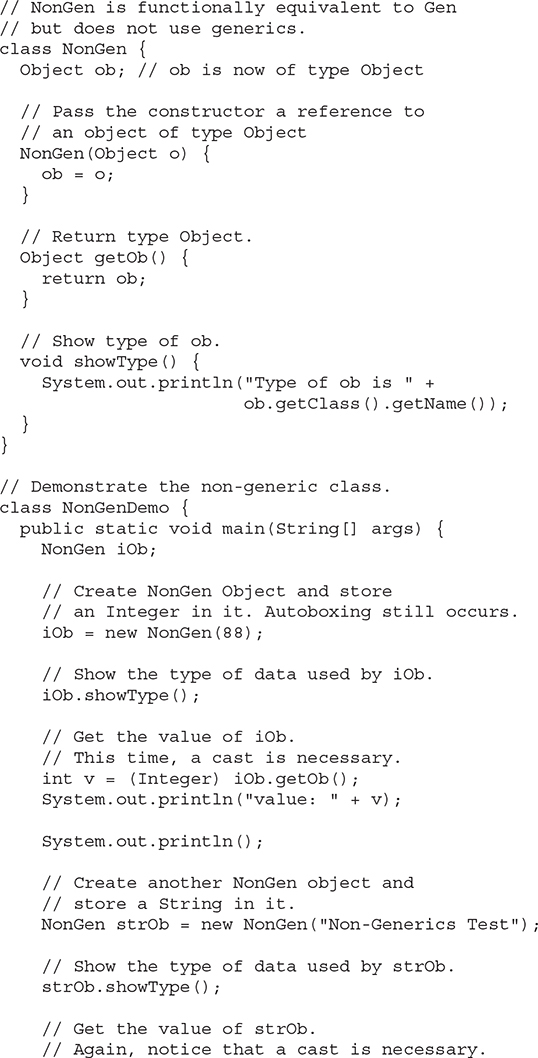

To understand the benefits of generics, first consider the following program that creates a non-generic equivalent of Gen:

There are several things of interest in this version. First, notice that NonGen replaces all uses of T with Object. This makes NonGen able to store any type of object, as can the generic version. However, it also prevents the Java compiler from having any real knowledge about the type of data actually stored in NonGen, which is bad for two reasons. First, explicit casts must be employed to retrieve the stored data. Second, many kinds of type mismatch errors cannot be found until run time. Let’s look closely at each problem.

Notice this line:

int v = (Integer) iOb.getOb();

Because the return type of getOb( ) is Object, the cast to Integer is necessary to enable that value to be auto-unboxed and stored in v. If you remove the cast, the program will not compile. With the generic version, this cast was implicit. In the non-generic version, the cast must be explicit. This is not only an inconvenience, but also a potential source of error.

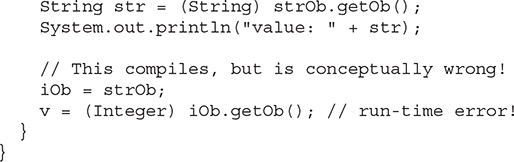

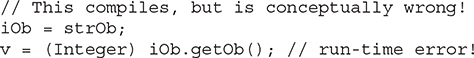

Now, consider the following sequence from near the end of the program:

Here, strOb is assigned to iOb. However, strOb refers to an object that contains a string, not an integer. This assignment is syntactically valid because all NonGen references are the same, and any NonGen reference can refer to any other NonGen object. However, the statement is semantically wrong, as the next line shows. Here, the return type of getOb( ) is cast to Integer, and then an attempt is made to assign this value to v. The trouble is that iOb now refers to an object that stores a String, not an Integer. Unfortunately, without the use of generics, the Java compiler has no way to know this. Instead, a run-time exception occurs when the cast to Integer is attempted. As you know, it is extremely bad to have run-time exceptions occur in your code!

The preceding sequence can’t occur when generics are used. If this sequence were attempted in the generic version of the program, the compiler would catch it and report an error, thus preventing a serious bug that results in a run-time exception. The ability to create type-safe code in which type-mismatch errors are caught at compile time is a key advantage of generics. Although using Object references to create “generic” code has always been possible, that code was not type safe, and its misuse could result in run-time exceptions. Generics prevent this from occurring. In essence, through generics, run-time errors are converted into compile-time errors. This is a major advantage.

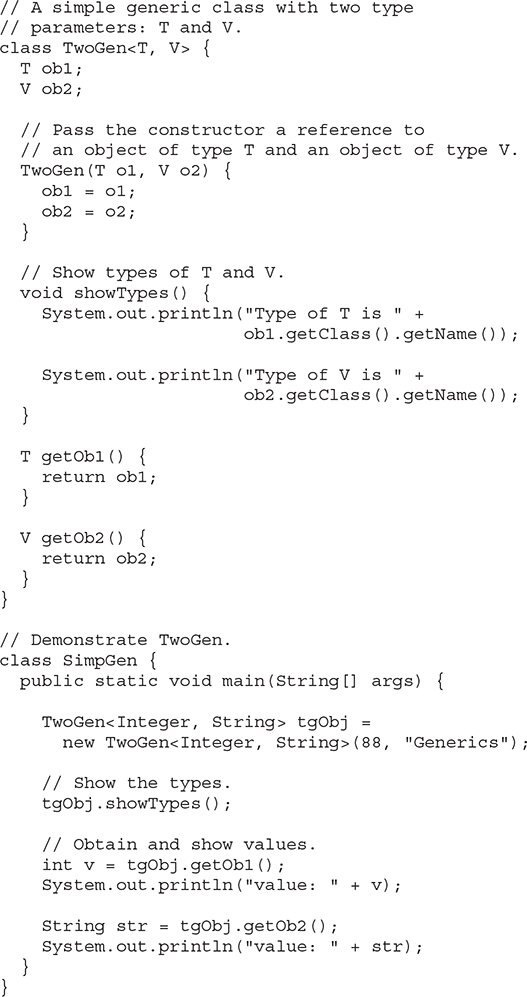

# A Generic Class with Two Type Parameters

You can declare more than one type parameter in a generic type. To specify two or more type parameters, simply use a comma-separated list. For example, the following TwoGen class is a variation of the Gen class that has two type parameters:

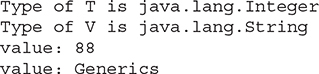

The output from this program is shown here:

Notice how TwoGen is declared:

class TwoGen\<T, V\> {

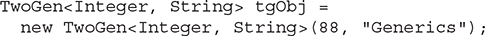

It specifies two type parameters: T and V, separated by a comma. Because it has two type parameters, two type arguments must be passed to TwoGen when an object is created, as shown next:

In this case, Integer is substituted for T, and String is substituted for V.

Although the two type arguments differ in this example, it is possible for both types to be the same. For example, the following line of code is valid:

TwoGen\<String, String\> x = new TwoGen\<String, String\> ("A", "B");

In this case, both T and V would be of type String. Of course, if the type arguments were always the same, then two type parameters would be unnecessary.

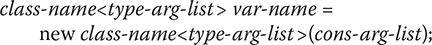

# The General Form of a Generic Class

The generics syntax shown in the preceding examples can be generalized. Here is the syntax for declaring a generic class:

class class-name<type-param-list > { // …

Here is the full syntax for declaring a reference to a generic class and instance creation:

# Bounded Types

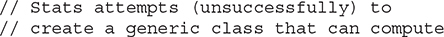

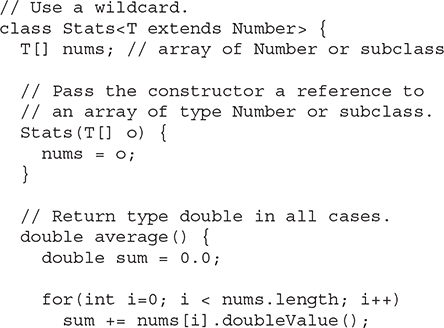

In the preceding examples, the type parameters could be replaced by any class type. This is fine for many purposes, but sometimes it is useful to limit the types that can be passed to a type parameter. For example, assume that you want to create a generic class that contains a method that returns the average of an array of numbers. Furthermore, you want to use the class to obtain the average of an array of any type of number, including integers, floats, and doubles. Thus, you want to specify the type of the numbers generically, using a type parameter. To create such a class, you might try something like this:

In Stats, the average( ) method attempts to obtain the double version of each number in the nums array by calling doubleValue( ). Because all numeric classes, such as Integer and Double, are subclasses of Number, and Number defines the doubleValue( ) method, this method is available to all numeric wrapper classes. The trouble is that the compiler has no way to know that you are intending to create Stats objects using only numeric types. Thus, when you try to compile Stats, an error is reported that indicates that the doubleValue( ) method is unknown. To solve this problem, you need some way to tell the compiler that you intend to pass only numeric types to T. Furthermore, you need some way to ensure that only numeric types are actually passed.

To handle such situations, Java provides bounded types. When specifying a type parameter, you can create an upper bound that declares the superclass from which all type arguments must be derived. This is accomplished through the use of an extends clause when specifying the type parameter, as shown here:

<T extends superclass\>

This specifies that T can only be replaced by superclass, or subclasses of superclass. Thus, superclass defines an inclusive, upper limit.

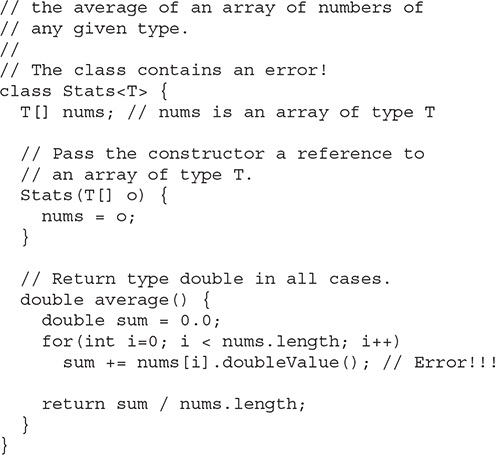

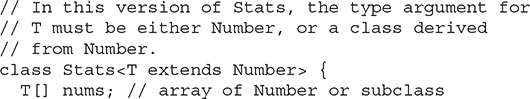

You can use an upper bound to fix the Stats class shown earlier by specifying Number as an upper bound, as shown here:

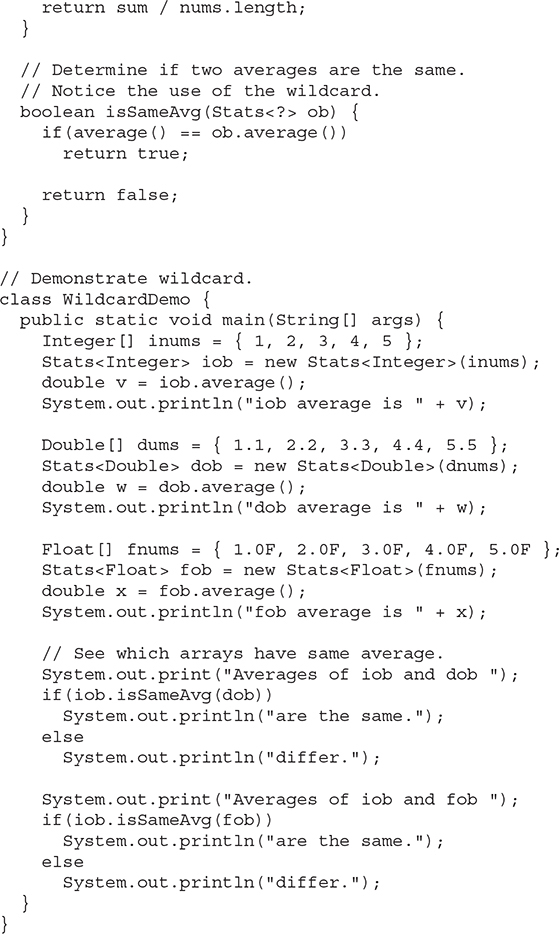

The output is shown here:

Notice how Stats is now declared by this line:

class Stats\<T extends Number\> {

Because the type T is now bounded by Number, the Java compiler knows that all objects of type T can call doubleValue( ) because it is a method declared by Number. This is, by itself, a major advantage. However, as an added bonus, the bounding of T also prevents nonnumeric Stats objects from being created. For example, if you try removing the comments from the lines at the end of the program, and then try recompiling, you will receive compile-time errors because String is not a subclass of Number.

In addition to using a class type as a bound, you can also use an interface type. In fact, you can specify multiple interfaces as bounds. Furthermore, a bound can include both a class type and one or more interfaces. In this case, the class type must be specified first. When a bound includes an interface type, only type arguments that implement that interface are legal. When specifying a bound that has a class and an interface, or multiple interfaces, use the & operator to connect them. This creates an intersection type. For example:

class Gen\<T extends MyClass & MyInterface\> { // ...

Here, T is bounded by a class called MyClass and an interface called MyInterface. Thus, any type argument passed to T must be a subclass of MyClass and implement MyInterface. As a point of interest, you can also use a type intersection in a cast.

# Using Wildcard Arguments

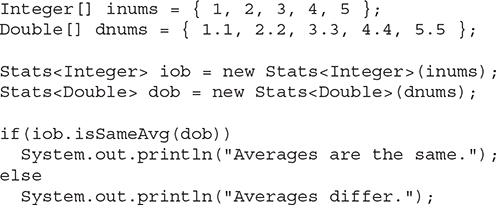

As useful as type safety is, sometimes it can get in the way of perfectly acceptable constructs. For example, given the Stats class shown at the end of the preceding section, assume that you want to add a method called isSameAvg( ) that determines if two Stats objects contain arrays that yield the same average, no matter what type of numeric data each object holds. For example, if one object contains the double values 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0, and the other object contains the integer values 2, 1, and 3, then the averages will be the same. One way to implement isSameAvg( ) is to pass it a Stats argument, and then compare the average of that argument against the invoking object, returning true only if the averages are the same. For example, you want to be able to call isSameAvg( ), as shown here:

At first, creating isSameAvg( ) seems like an easy problem. Because Stats is generic and its average( ) method can work on any type of Stats object, it seems that creating isSameAvg( ) would be straightforward. Unfortunately, trouble starts as soon as you try to declare a parameter of type Stats. Because Stats is a parameterized type, what do you specify for Stats’ type parameter when you declare a parameter of that type?

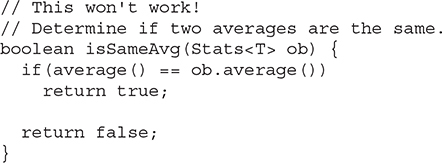

At first, you might think of a solution like this, in which T is used as the type parameter:

The trouble with this attempt is that it will work only with other Stats objects whose type is the same as the invoking object. For example, if the invoking object is of type Stats<Integer>, then the parameter ob must also be of type Stats<Integer>. It can’t be used to compare the average of an object of type Stats<Double> with the average of an object of type Stats<Short>, for example. Therefore, this approach won’t work except in a very narrow context and does not yield a general (that is, generic) solution.

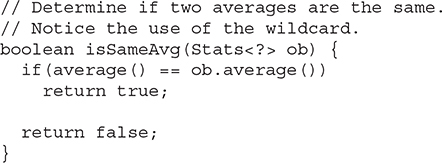

To create a generic isSameAvg( ) method, you must use another feature of Java generics: the wildcard argument. The wildcard argument is specified by the ?, and it represents an unknown type. Using a wildcard, here is one way to write the isSameAvg( ) method:

Here, Stats<?> matches any Stats object, allowing any two Stats objects to have their averages compared. The following program demonstrates this:

The output is shown here:

One last point: It is important to understand that the wildcard does not affect what type of Stats objects can be created. This is governed by the extends clause in the Stats declaration. The wildcard simply matches any valid Stats object.

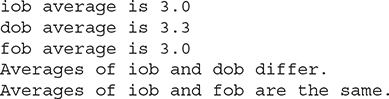

# Bounded Wildcards

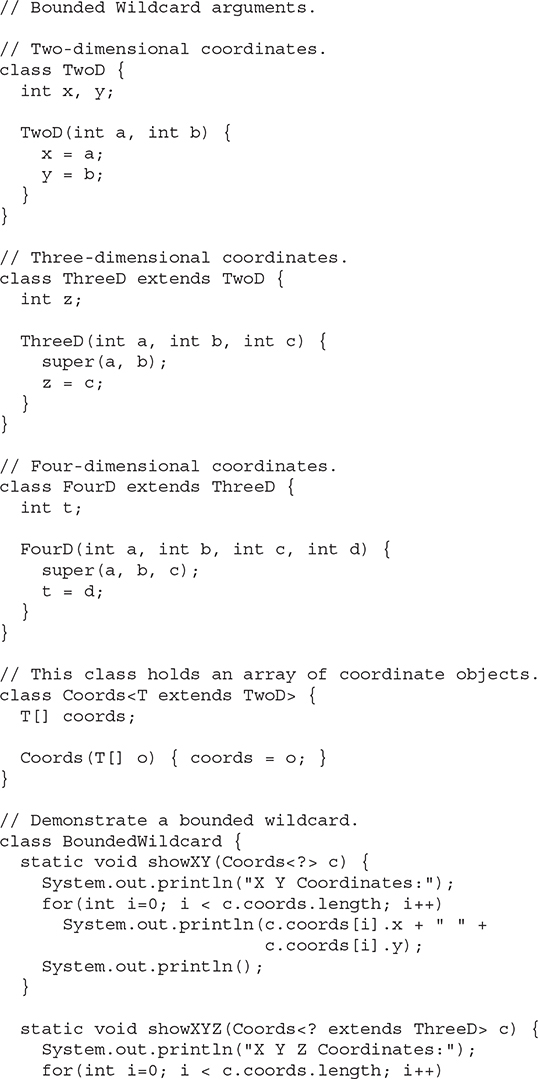

Wildcard arguments can be bounded in much the same way that a type parameter can be bounded. A bounded wildcard is especially important when you are creating a generic type that will operate on a class hierarchy. To understand why, let’s work through an example. Consider the following hierarchy of classes that encapsulate coordinates:

At the top of the hierarchy is TwoD, which encapsulates a two-dimensional, XY coordinate. TwoD is inherited by ThreeD, which adds a third dimension, creating an XYZ coordinate. ThreeD is inherited by FourD, which adds a fourth dimension (time), yielding a four-dimensional coordinate.

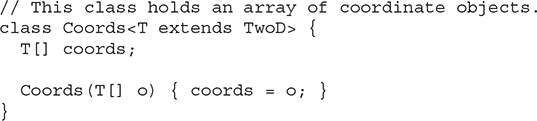

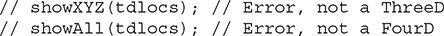

Shown next is a generic class called Coords, which stores an array of coordinates:

Notice that Coords specifies a type parameter bounded by TwoD. This means that any array stored in a Coords object will contain objects of type TwoD or one of its subclasses.

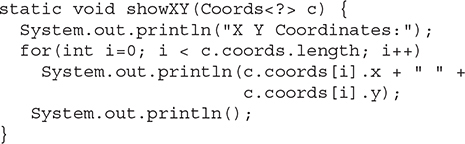

Now, assume that you want to write a method that displays the X and Y coordinates for each element in the coords array of a Coords object. Because all types of Coords objects have at least two coordinates (X and Y), this is easy to do using a wildcard, as shown here:

Because Coords is a bounded generic type that specifies TwoD as an upper bound, all objects that can be used to create a Coords object will be arrays of type TwoD, or of classes derived from TwoD. Thus, showXY( ) can display the contents of any Coords object.

However, what if you want to create a method that displays the X, Y, and Z coordinates of a ThreeD or FourD object? The trouble is that not all Coords objects will have three coordinates, because a Coords<TwoD> object will only have X and Y. Therefore, how do you write a method that displays the X, Y, and Z coordinates for Coords<ThreeD> and Coords<FourD> objects, while preventing that method from being used with Coords<TwoD> objects? The answer is the bounded wildcard argument.

A bounded wildcard specifies either an upper bound or a lower bound for the type argument. This enables you to restrict the types of objects upon which a method will operate. The most common bounded wildcard is the upper bound, which is created using an extends clause in much the same way it is used to create a bounded type.

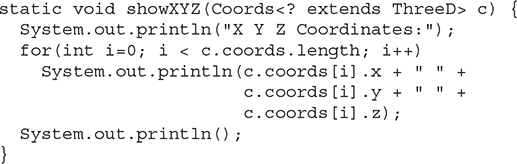

Using a bounded wildcard, it is easy to create a method that displays the X, Y, and Z coordinates of a Coords object, if that object actually has those three coordinates. For example, the following showXYZ( ) method shows the X, Y, and Z coordinates of the elements stored in a Coords object, if those elements are actually of type ThreeD (or are derived from ThreeD):

Notice that an extends clause has been added to the wildcard in the declaration of parameter c. It states that the ? can match any type as long as it is ThreeD, or a class derived from ThreeD. Thus, the extends clause establishes an upper bound that the ? can match. Because of this bound, showXYZ( ) can be called with references to objects of type Coords<ThreeD> or Coords<FourD>, but not with a reference of type Coords<TwoD>. Attempting to call showXZY( ) with a Coords<TwoD> reference results in a compile-time error, thus ensuring type safety.

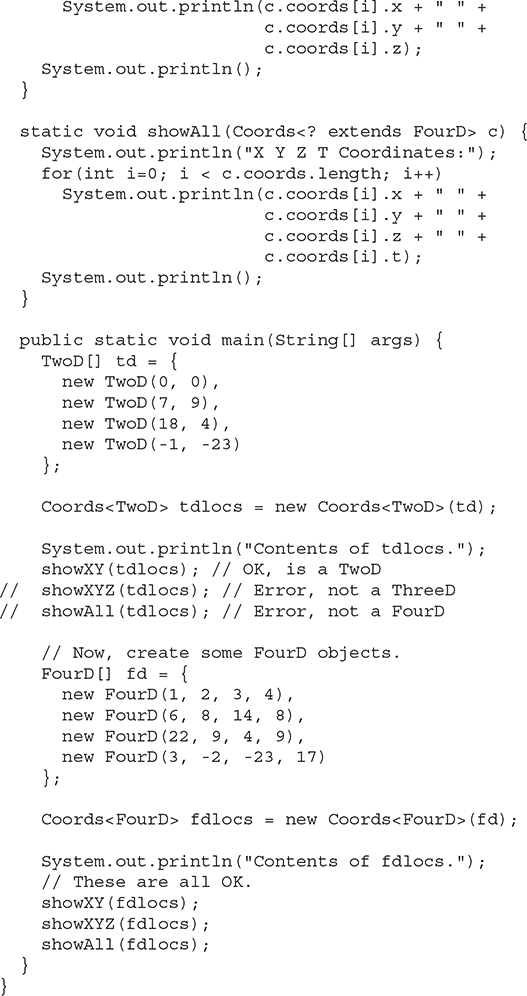

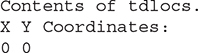

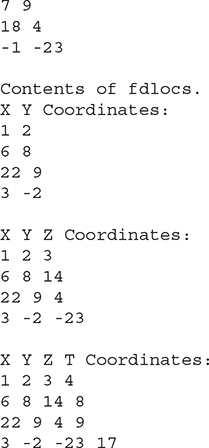

Here is an entire program that demonstrates the actions of a bounded wildcard argument:

The output from the program is shown here:

Notice these commented-out lines:

Because tdlocs is a Coords(TwoD) object, it cannot be used to call showXYZ( ) or showAll( ) because bounded wildcard arguments in their declarations prevent it. To prove this to yourself, try removing the comment symbols, and then attempt to compile the program. You will receive compilation errors because of the type mismatches.

In general, to establish an upper bound for a wildcard, use the following type of wildcard expression:

<? extends superclass\>

where superclass is the name of the class that serves as the upper bound. Remember, this is an inclusive clause because the class forming the upper bound (that is, specified by superclass) is also within bounds.

You can also specify a lower bound for a wildcard by adding a super clause to a wildcard declaration. Here is its general form:

<? super subclass\>

In this case, only classes that are superclasses of subclass are acceptable arguments. This is an inclusive clause.

# Creating a Generic Method

As the preceding examples have shown, methods inside a generic class can make use of a class’s type parameter and are, therefore, automatically generic relative to the type parameter. However, it is possible to declare a generic method that uses one or more type parameters of its own. Furthermore, it is possible to create a generic method that is enclosed within a non-generic class.

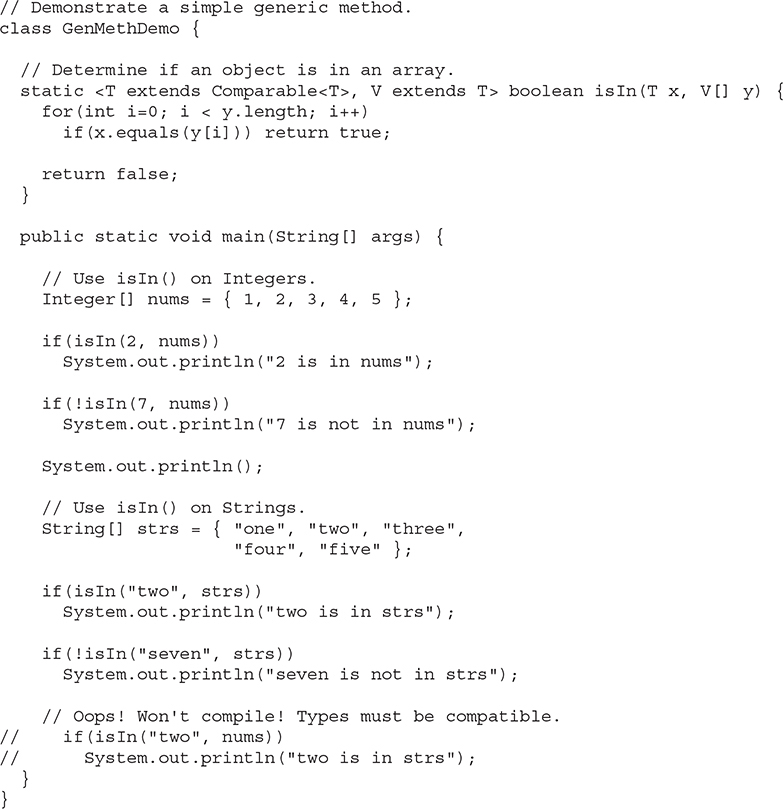

Let’s begin with an example. The following program declares a non-generic class called GenMethDemo and a static generic method within that class called isIn( ). The isIn( ) method determines if an object is a member of an array. It can be used with any type of object and array as long as the array contains objects that are compatible with the type of the object being sought.

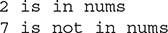

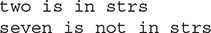

The output from the program is shown here:

Let’s examine isIn( ) closely. First, notice how it is declared by this line:

static \<T extends Comparable\<T\>, V extends T\> boolean isIn(T x, V[] y) {

The type parameters are declared before the return type of the method. Also note that T extends Comparable<T>. Comparable is an interface declared in java.lang. A class that implements Comparable defines objects that can be ordered. Thus, requiring an upper bound of Comparable ensures that isIn( ) can be used only with objects that are capable of being compared. Comparable is generic, and its type parameter specifies the type of objects that it compares. (Shortly, you will see how to create a generic interface.) Next, notice that the type V is upper-bounded by T. Thus, V must either be the same as type T, or a subclass of T. This relationship enforces that isIn( ) can be called only with arguments that are compatible with each other. Also notice that isIn( ) is static, enabling it to be called independently of any object. Understand, though, that generic methods can be either static or non-static. There is no restriction in this regard.

Now, notice how isIn( ) is called within main( ) by use of the normal call syntax, without the need to specify type arguments. This is because the types of the arguments are automatically discerned, and the types of T and V are adjusted accordingly. For example, in the first call:

if(isIn(2, nums))

the type of the first argument is Integer (due to autoboxing), which causes Integer to be substituted for T. The base type of the second argument is also Integer, which makes Integer a substitute for V, too. In the second call, String types are used, and the types of T and V are replaced by String.

Although type inference will be sufficient for most generic method calls, you can explicitly specify the type argument if needed. For example, here is how the first call to isIn( ) looks when the type arguments are specified:

GenMethDemo.\<Integer, Integer\>isIn(2, nums)

Of course, in this case, there is nothing gained by specifying the type arguments. Furthermore, JDK 8 improved type inference as it relates to methods. As a result, today there are fewer cases in which explicit type arguments are needed.

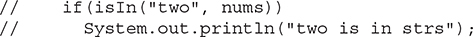

Now, notice the commented-out code, shown here:

If you remove the comments and then try to compile the program, you will receive an error. The reason is that the type parameter V is bounded by T in the extends clause in V’s declaration. This means that V must be either type T, or a subclass of T. In this case, the first argument is of type String, making T into String, but the second argument is of type Integer, which is not a subclass of String. This causes a compile-time type-mismatch error. This ability to enforce type safety is one of the most important advantages of generic methods.

The syntax used to create isIn( ) can be generalized. Here is the syntax for a generic method:

<type-param-list > ret-type meth-name (param-list) { // …

In all cases, type-param-list is a comma-separated list of type parameters. Notice that for a generic method, the type parameter list precedes the return type.

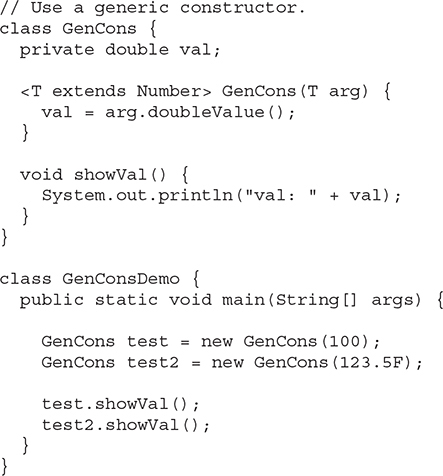

# Generic Constructors

It is possible for constructors to be generic, even if their class is not. For example, consider the following short program:

The output is shown here:

Because GenCons( ) specifies a parameter of a generic type, which must be a subclass of Number, GenCons( ) can be called with any numeric type, including Integer, Float, or Double. Therefore, even though GenCons is not a generic class, its constructor is generic.

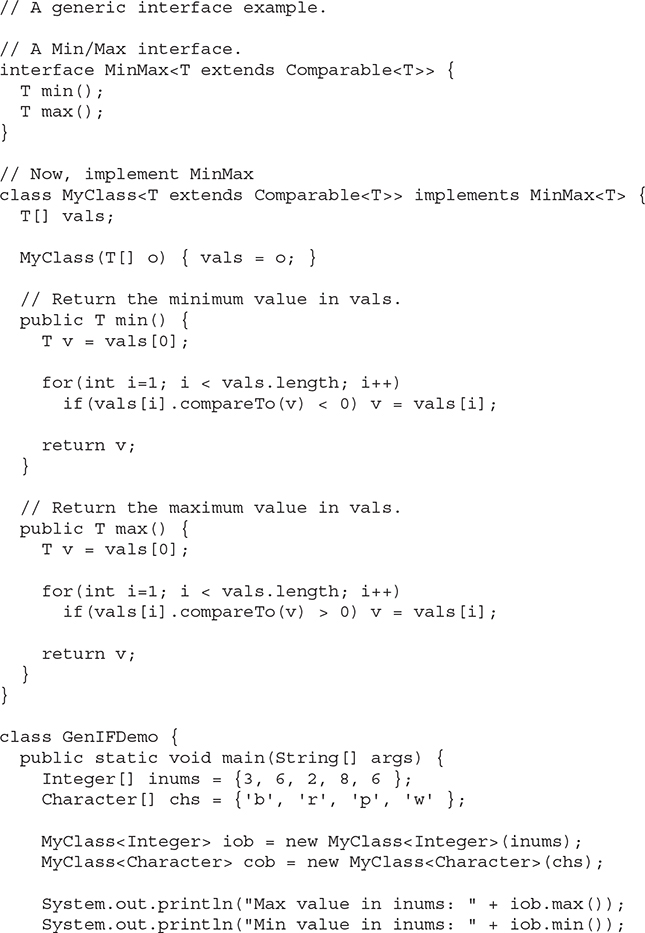

# Generic Interfaces

In addition to generic classes and methods, you can also have generic interfaces. Generic interfaces are specified just like generic classes. Here is an example. It creates an interface called MinMax that declares the methods min( ) and max( ), which are expected to return the minimum and maximum value of some set of objects.

The output is shown here:

Although most aspects of this program should be easy to understand, a couple of key points need to be made. First, notice that MinMax is declared like this:

interface MinMax\<T extends Comparable\<T\>\> {

In general, a generic interface is declared in the same way as is a generic class. In this case, the type parameter is T, and its upper bound is Comparable. As explained earlier, Comparable is an interface defined by java.lang that specifies how objects are compared. Its type parameter specifies the type of the objects being compared.

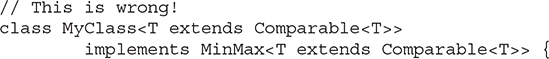

Next, MinMax is implemented by MyClass. Notice the declaration of MyClass, shown here:

class MyClass\<T extends Comparable\<T\>\> implements MinMax\<T\> {

Pay special attention to the way that the type parameter T is declared by MyClass and then passed to MinMax. Because MinMax requires a type that implements Comparable, the implementing class (MyClass in this case) must specify the same bound. Furthermore, once this bound has been established, there is no need to specify it again in the implements clause. In fact, it would be wrong to do so. For example, this line is incorrect and won’t compile:

Once the type parameter has been established, it is simply passed to the interface without further modification.

In general, if a class implements a generic interface, then that class must also be generic, at least to the extent that it takes a type parameter that is passed to the interface. For example, the following attempt to declare MyClass is in error:

class MyClass implements MinMax\<T\> { // Wrong!

Because MyClass does not declare a type parameter, there is no way to pass one to MinMax. In this case, the identifier T is simply unknown, and the compiler reports an error. Of course, if a class implements a specific type of generic interface, such as shown here:

class MyClass implements MinMax\<Integer\> { // OK

then the implementing class does not need to be generic.

The generic interface offers two benefits. First, it can be implemented for different types of data. Second, it allows you to put constraints (that is, bounds) on the types of data for which the interface can be implemented. In the MinMax example, only types that implement the Comparable interface can be passed to T.

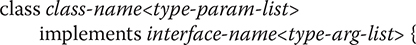

Here is the generalized syntax for a generic interface:

interface interface-name<type-param-list\> { // …

Here, type-param-list is a comma-separated list of type parameters. When a generic interface is implemented, you must specify the type arguments, as shown here:

# Raw Types and Legacy Code

Because support for generics did not exist prior to JDK 5, it was necessary to provide some transition path from old, pre-generics code. Furthermore, this transition path had to enable pre-generics code to remain functional while at the same time being compatible with generics. In other words, pre-generics code had to be able to work with generics, and generic code had to be able to work with pre-generics code.

To handle the transition to generics, Java allows a generic class to be used without any type arguments. This creates a raw type for the class. This raw type is compatible with legacy code, which has no knowledge of generics. The main drawback to using the raw type is that the type safety of generics is lost.

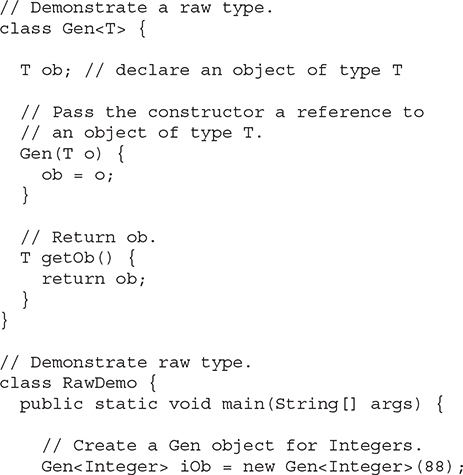

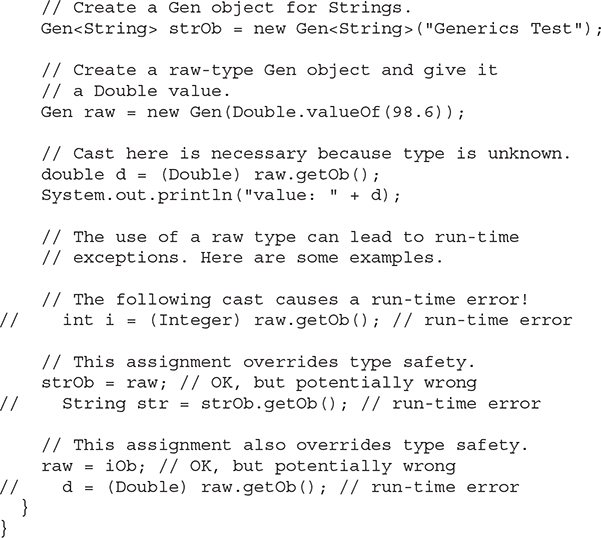

Here is an example that shows a raw type in action:

This program contains several interesting things. First, a raw type of the generic Gen class is created by the following declaration:

Gen raw = new Gen(Double.valueOf(98.6));

Notice that no type arguments are specified. In essence, this creates a Gen object whose type T is replaced by Object.

A raw type is not type safe. Thus, a variable of a raw type can be assigned a reference to any type of Gen object. The reverse is also allowed; a variable of a specific Gen type can be assigned a reference to a raw Gen object. However, both operations are potentially unsafe because the type checking mechanism of generics is circumvented.

This lack of type safety is illustrated by the commented-out lines at the end of the program. Let’s examine each case. First, consider the following situation:

// int i = (Integer) raw.getOb(); // run-time error

In this statement, the value of ob inside raw is obtained, and this value is cast to Integer. The trouble is that raw contains a Double value, not an integer value. However, this cannot be detected at compile time because the type of raw is unknown. Thus, this statement fails at run time.

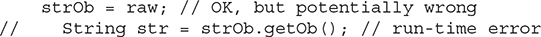

The next sequence assigns to a strOb (a reference of type Gen<String>) a reference to a raw Gen object:

The assignment itself is syntactically correct, but questionable. Because strOb is of type Gen<String>, it is assumed to contain a String. However, after the assignment, the object referred to by strOb contains a Double. Thus, at run time, when an attempt is made to assign the contents of strOb to str, a run-time error results because strOb now contains a Double. Thus, the assignment of a raw reference to a generic reference bypasses the type-safety mechanism.

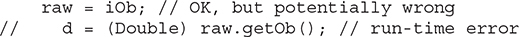

The following sequence inverts the preceding case:

Here, a generic reference is assigned to a raw reference variable. Although this is syntactically correct, it can lead to problems, as illustrated by the second line. In this case, raw now refers to an object that contains an Integer object, but the cast assumes that it contains a Double. This error cannot be prevented at compile time. Rather, it causes a run-time error.

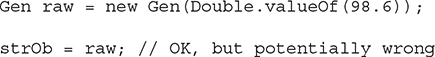

Because of the potential for danger inherent in raw types, javac displays unchecked warnings when a raw type is used in a way that might jeopardize type safety. In the preceding program, these lines generate unchecked warnings:

In the first line, it is the call to the Gen constructor without a type argument that causes the warning. In the second line, it is the assignment of a raw reference to a generic variable that generates the warning.

At first, you might think that this line should also generate an unchecked warning, but it does not:

raw = iOb; // OK, but potentially wrong

No compiler warning is issued because the assignment does not cause any further loss of type safety than had already occurred when raw was created.

One final point: You should limit the use of raw types to those cases in which you must mix legacy code with newer, generic code. Raw types are simply a transitional feature and not something that should be used for new code.

# Generic Class Hierarchies

Generic classes can be part of a class hierarchy in just the same way as a non-generic class. Thus, a generic class can act as a superclass or be a subclass. The key difference between generic and non-generic hierarchies is that in a generic hierarchy, any type arguments needed by a generic superclass must be passed up the hierarchy by all subclasses. This is similar to the way that constructor arguments must be passed up a hierarchy.

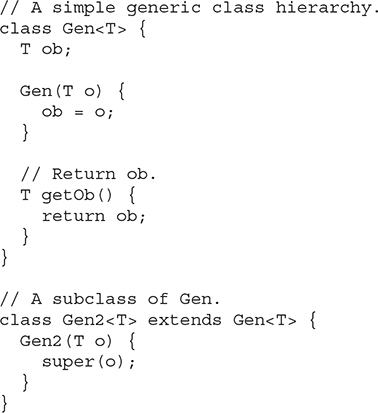

# Using a Generic Superclass

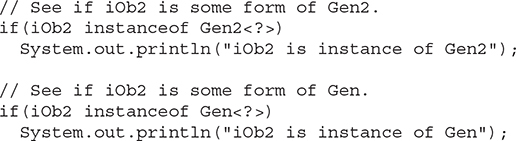

Here is a simple example of a hierarchy that uses a generic superclass:

In this hierarchy, Gen2 extends the generic class Gen. Notice how Gen2 is declared by the following line:

class Gen2\<T\> extends Gen\<T\> {

The type parameter T is specified by Gen2 and is also passed to Gen in the extends clause. This means that whatever type is passed to Gen2 will also be passed to Gen. For example, this declaration,

Gen2\<Integer\> num = new Gen2\<Integer\>(100);

passes Integer as the type parameter to Gen. Thus, the ob inside the Gen portion of Gen2 will be of type Integer.

Notice also that Gen2 does not use the type parameter T except to support the Gen superclass. Thus, even if a subclass of a generic superclass would otherwise not need to be generic, it still must specify the type parameter(s) required by its generic superclass.

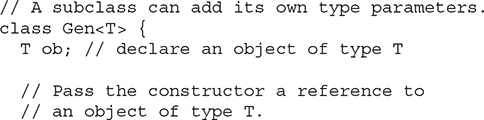

Of course, a subclass is free to add its own type parameters, if needed. For example, here is a variation on the preceding hierarchy in which Gen2 adds a type parameter of its own:

Notice the declaration of this version of Gen2, which is shown here:

class Gen2\<T, V\> extends Gen\<T\> {

Here, T is the type passed to Gen, and V is the type that is specific to Gen2. V is used to declare an object called ob2, and as a return type for the method getOb2( ). In main( ), a Gen2 object is created in which type parameter T is String, and type parameter V is Integer. The program displays the following, expected, result:

Value is: 99

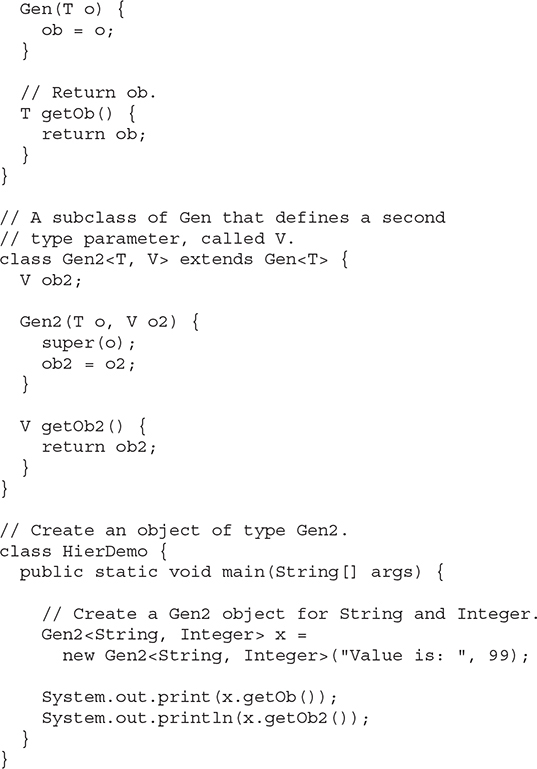

# A Generic Subclass

It is perfectly acceptable for a non-generic class to be the superclass of a generic subclass. For example, consider this program:

The output from the program is shown here:

Hello 47

In the program, notice how Gen inherits NonGen in the following declaration:

class Gen\<T\> extends NonGen {

Because NonGen is not generic, no type argument is specified. Thus, even though Gen declares the type parameter T, it is not needed by (nor can it be used by) NonGen. Thus, NonGen is inherited by Gen in the normal way. No special conditions apply.

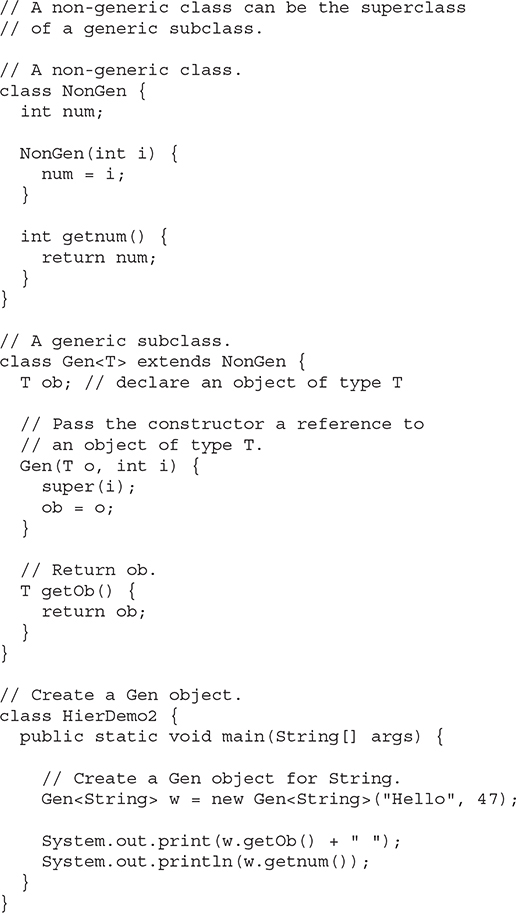

# Run-Time Type Comparisons Within a Generic Hierarchy

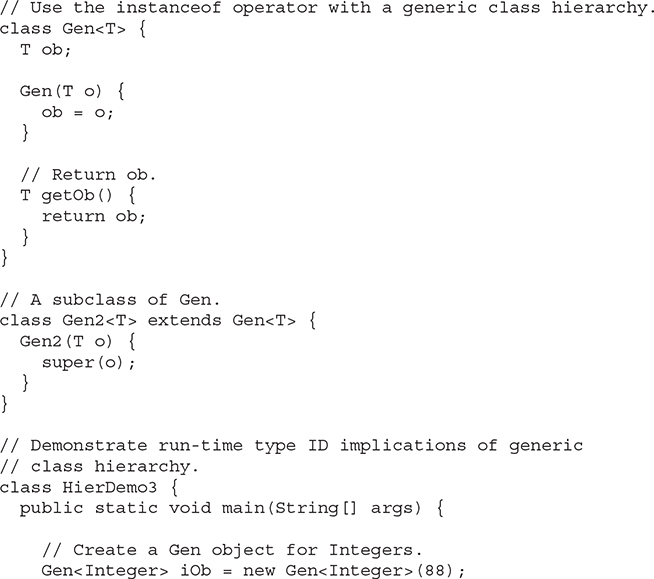

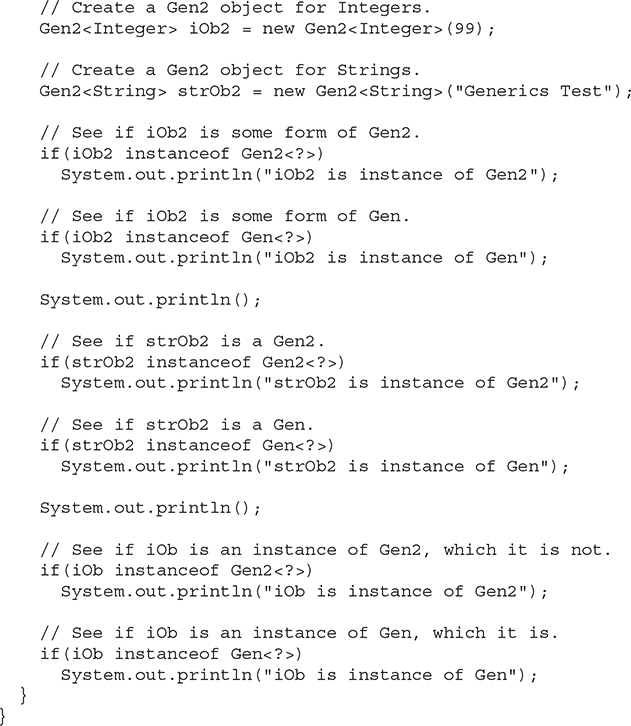

Recall the run-time type information operator instanceof that was introduced in Chapter 13. As explained, instanceof determines if an object is an instance of a class. It returns true if an object is of the specified type or can be cast to the specified type. The instanceof operator can be applied to objects of generic classes. The following class demonstrates some of the type compatibility implications of a generic hierarchy:

The output from the program is shown here:

In this program, Gen2 is a subclass of Gen, which is generic on type parameter T. In main( ), three objects are created. The first is iOb, which is an object of type Gen<Integer>. The second is iOb2, which is an instance of Gen2<Integer>. Finally, strOb2 is an object of type Gen2<String>.

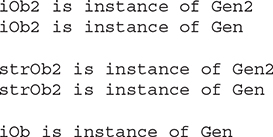

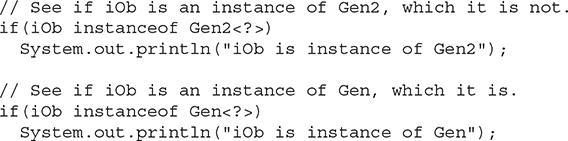

Then, the program performs these instanceof tests on the type of iOb2:

As the output shows, both succeed. In the first test, iOb2 is checked against Gen2<?>. This test succeeds because it simply confirms that iOb2 is an object of some type of Gen2 object. The use of the wildcard enables instanceof to determine if iOb2 is an object of any type of Gen2. Next, iOb2 is tested against Gen<?>, the superclass type. This is also true because iOb2 is some form of Gen, the superclass. The next few lines in main( ) show the same sequence (and same results) for strOb2.

Next, iOb, which is an instance of Gen<Integer> (the superclass), is tested by these lines:

The first if fails because iOb is not some type of Gen2 object. The second test succeeds because iOb is some type of Gen object.

# Casting

You can cast one instance of a generic class into another only if the two are otherwise compatible and their type arguments are the same. For example, assuming the foregoing program, this cast is legal:

(Gen\<Integer\>) iOb2 // legal

because iOb2 includes an instance of Gen<Integer>. But, this cast:

(Gen\<Long\>) iOb2 // illegal

is not legal because iOb2 is not an instance of Gen<Long>.

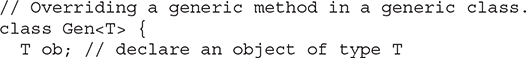

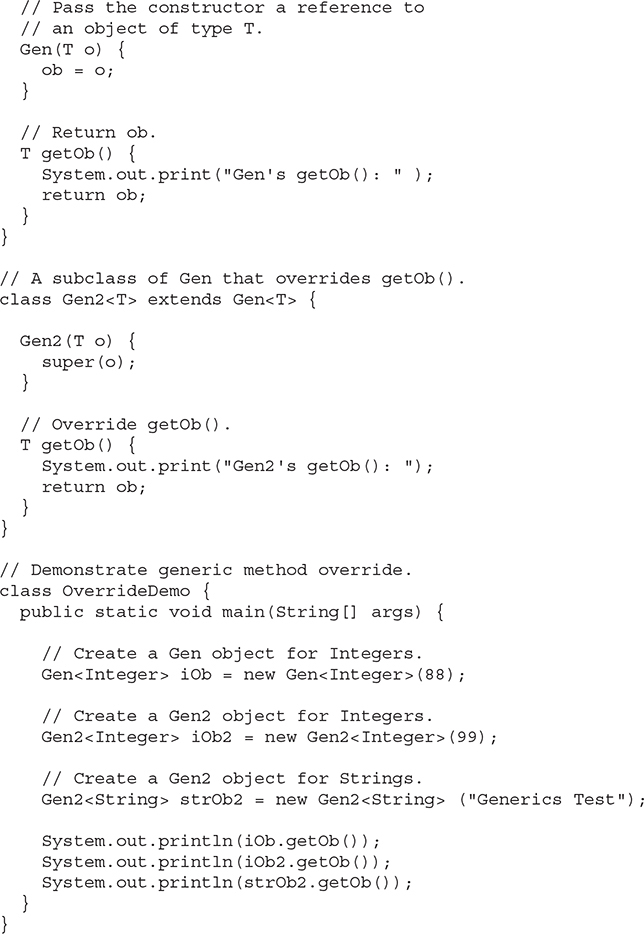

# Overriding Methods in a Generic Class

A method in a generic class can be overridden just like any other method. For example, consider this program in which the method getOb( ) is overridden:

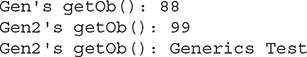

The output is shown here:

As the output confirms, the overridden version of getOb( ) is called for objects of type Gen2, but the superclass version is called for objects of type Gen.

# Type Inference with Generics

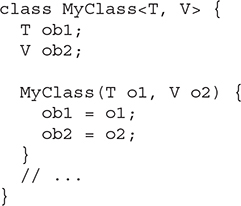

Beginning with JDK 7, it became possible to shorten the syntax used to create an instance of a generic type. To begin, consider the following generic class:

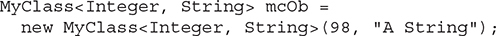

Prior to JDK 7, to create an instance of MyClass, you would have needed to use a statement similar to the following:

Here, the type arguments (which are Integer and String) are specified twice: first, when mcOb is declared, and second, when a MyClass instance is created via new. Since generics were introduced by JDK 5, this is the form required by all versions of Java prior to JDK 7. Although there is nothing wrong, per se, with this form, it is a bit more verbose than it needs to be. In the new clause, the type of the type arguments can be readily inferred from the type of mcOb; therefore, there is really no reason that they need to be specified a second time. To address this situation, JDK 7 added a syntactic element that lets you avoid the second specification.

Today the preceding declaration can be rewritten as shown here:

MyClass\<Integer, String\> mcOb = new MyClass\<\>(98, "A String");

Notice that the instance creation portion simply uses <>, which is an empty type argument list. This is referred to as the diamond operator. It tells the compiler to infer the type arguments needed by the constructor in the new expression. The principal advantage of this type-inference syntax is that it shortens what are sometimes quite long declaration statements.

The preceding can be generalized. When type inference is used, the declaration syntax for a generic reference and instance creation has this general form:

class-name<type-arg-list > var-name = new class-name <>(cons-arg-list);

Here, the type argument list of the constructor in the new clause is empty.

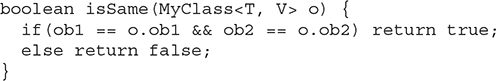

Type inference can also be applied to parameter passing. For example, if the following method is added to MyClass,

then the following call is legal:

if(mcOb.isSame(new MyClass\<\>(1, "test"))) System.out.println("Same");

In this case, the type arguments for the argument passed to isSame( ) can be inferred from the parameter’s type.

Most of the examples in this book will continue to use the full syntax when declaring instances of generic classes. This way, the examples will work with any Java compiler that supports generics. Using the full-length syntax also makes it very clear precisely what is being created, which is important in sample code shown in a book. However, in your own code, the use of the type-inference syntax will streamline your declarations.

# Local Variable Type Inference and Generics

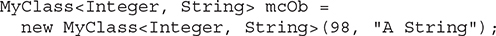

As just explained, type inference is already supported for generics through the use of the diamond operator. However, you can also use the local variable type inference feature added by JDK 10 with a generic class. For example, assuming MyClass used in the preceding section, this declaration:

can be rewritten like this using local variable type inference:

var mcOb = new MyClass\<Integer, String\>(98, "A String");

In this case, the type of mcOb is inferred to be MyClass<Integer, String> because that is the type of its initializer. Also notice that the use of var results in a shorter declaration than would be the case otherwise. In general, generic type names can often be quite long and (in some cases) complicated. The use of var is another way to substantially shorten such declarations. For the same reasons as just explained for the diamond operator, the remaining examples in this book will continue to use the full generic syntax, but in your own code the use of local variable type inference can be quite helpful.

# Erasure

Usually, it is not necessary to know the details about how the Java compiler transforms your source code into object code. However, in the case of generics, some general understanding of the process is important because it explains why the generic features work as they do—and why their behavior is sometimes a bit surprising. For this reason, a brief discussion of how generics are implemented in Java is in order.

An important constraint that governed the way that generics were added to Java was the need for compatibility with previous versions of Java. Simply put, generic code had to be compatible with preexisting, non-generic code. Thus, any changes to the syntax of the Java language, or to the JVM, had to avoid breaking older code. The way Java implements generics while satisfying this constraint is through the use of erasure.

In general, here is how erasure works: When your Java code is compiled, all generic type information is removed (erased). This means replacing type parameters with their bound type, which is Object if no explicit bound is specified, and then applying the appropriate casts (as determined by the type arguments) to maintain type compatibility with the types specified by the type arguments. The compiler also enforces this type compatibility. This approach to generics means that no type parameters exist at run time. They are simply a source-code mechanism.

# Bridge Methods

Occasionally, the compiler will need to add a bridge method to a class to handle situations in which the type erasure of an overriding method in a subclass does not produce the same erasure as the method in the superclass. In this case, a method is generated that uses the type erasure of the superclass, and this method calls the method that has the type erasure specified by the subclass. Of course, bridge methods only occur at the bytecode level, are not seen by you, and are not available for your use.

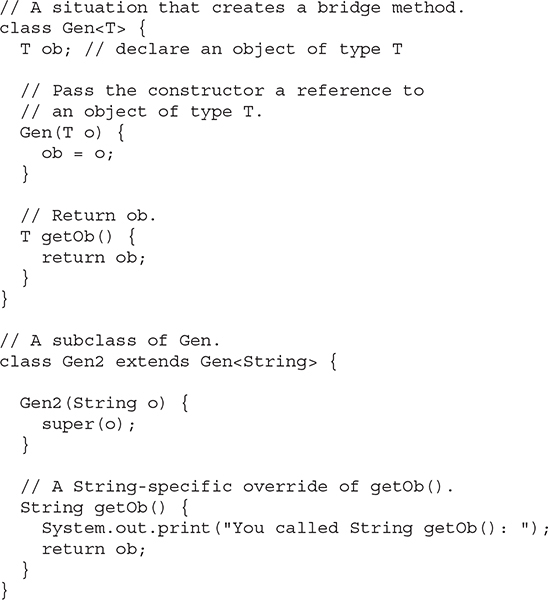

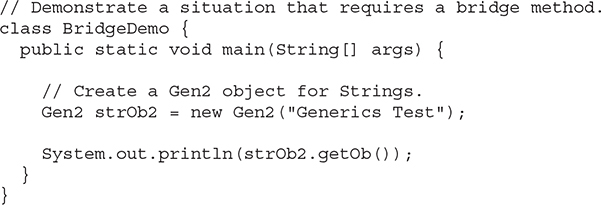

Although bridge methods are not something that you will normally need to be concerned with, it is still instructive to see a situation in which one is generated. Consider the following program:

In the program, the subclass Gen2 extends Gen, but does so using a String-specific version of Gen, as its declaration shows:

class Gen2 extends Gen\<String\> {

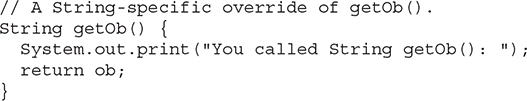

Furthermore, inside Gen2, getOb( ) is overridden with String specified as the return type:

All of this is perfectly acceptable. The only trouble is that because of type erasure, the expected form of getOb( ) will be

Object getOb() { // ...

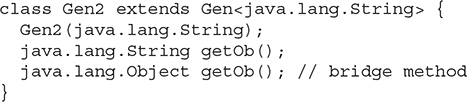

To handle this problem, the compiler generates a bridge method with the preceding signature that calls the String version. Thus, if you examine the class file for Gen2 by using javap, you will see the following methods:

As you can see, the bridge method has been included. (The comment was added by the author and not by javap, and the precise output you see may vary based on the version of Java that you are using.)

There is one last point to make about this example. Notice that the only difference between the two getOb( ) methods is their return type. Normally, this would cause an error, but because this does not occur in your source code, it does not cause a problem and is handled correctly by the JVM.

# Ambiguity Errors

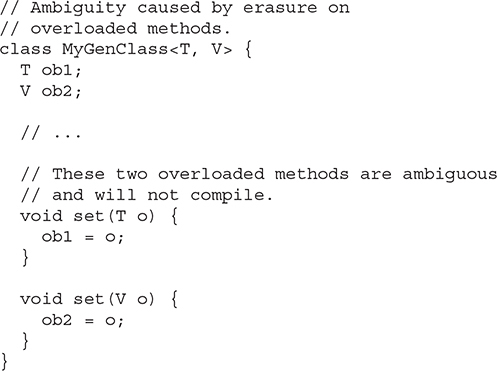

The inclusion of generics gives rise to another type of error that you must guard against: ambiguity. Ambiguity errors occur when erasure causes two seemingly distinct generic declarations to resolve to the same erased type, causing a conflict. Here is an example that involves method overloading:

Notice that MyGenClass declares two generic types: T and V. Inside MyGenClass, an attempt is made to overload set( ) based on parameters of type T and V. This looks reasonable because T and V appear to be different types. However, there are two ambiguity problems here.

First, as MyGenClass is written, there is no requirement that T and V actually be different types. For example, it is perfectly correct (in principle) to construct a MyGenClass object as shown here:

MyGenClass\<String, String\> obj = new MyGenClass\<String, String\>()

In this case, both T and V will be replaced by String. This makes both versions of set( ) identical, which is, of course, an error.

The second and more fundamental problem is that the type erasure of set( ) reduces both versions to the following:

void set(Object o) { // ...

Thus, the overloading of set( ) as attempted in MyGenClass is inherently ambiguous.

Ambiguity errors can be tricky to fix. For example, if you know that V will always be some type of Number, you might try to fix MyGenClass by rewriting its declaration as shown here:

class MyGenClass\<T, V extends Number\> { // almost OK!

This change causes MyGenClass to compile, and you can even instantiate objects like the one shown here:

MyGenClass\<String, Number\> x = new MyGenClass\<String, Number\>();

This works because Java can accurately determine which method to call. However, ambiguity returns when you try this line:

MyGenClass\<Number, Number\> x = new MyGenClass\<Number, Number\>();

In this case, since both T and V are Number, which version of set( ) is to be called? The call to set( ) is now ambiguous.

Frankly, in the preceding example, it would be much better to use two separate method names, rather than trying to overload set( ). Often, the solution to ambiguity involves the restructuring of the code, because ambiguity frequently means that you have a conceptual error in your design.

# Some Generic Restrictions

There are a few restrictions that you need to keep in mind when using generics. They involve creating objects of a type parameter, static members, exceptions, and arrays. Each is examined here.

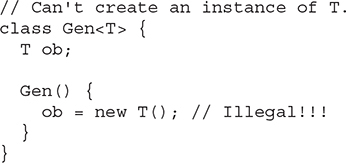

# Type Parameters Can’t Be Instantiated

It is not possible to create an instance of a type parameter. For example, consider this class:

Here, it is illegal to attempt to create an instance of T. The reason should be easy to understand: the compiler does not know what type of object to create. T is simply a placeholder.

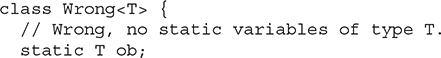

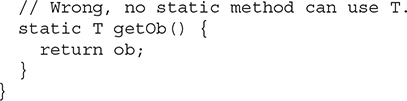

# Restrictions on Static Members

No static member can use a type parameter declared by the enclosing class. For example, both of the static members of this class are illegal:

Although you can’t declare static members that use a type parameter declared by the enclosing class, you can declare static generic methods, which define their own type parameters, as was done earlier in this chapter.

# Generic Array Restrictions

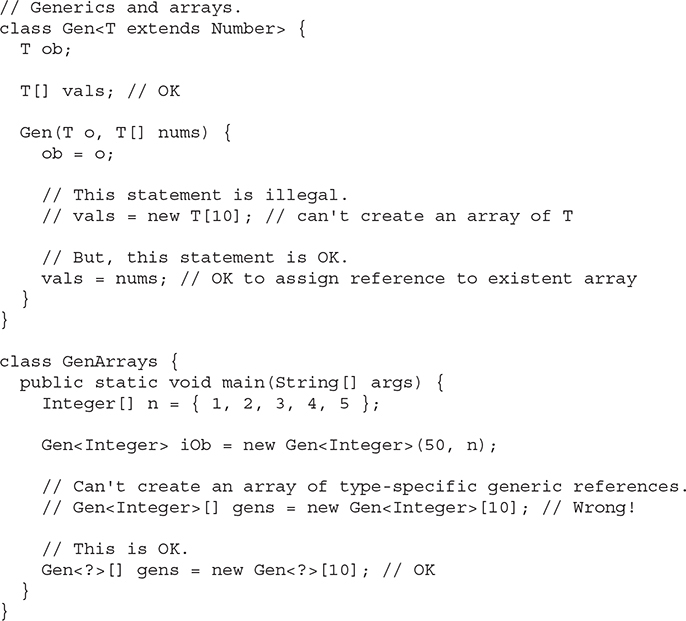

There are two important generics restrictions that apply to arrays. First, you cannot instantiate an array whose element type is a type parameter. Second, you cannot create an array of type-specific generic references. The following short program shows both situations:

As the program shows, it’s valid to declare a reference to an array of type T, as this line does:

T[] vals; // OK

But, you cannot instantiate an array of T, as this commented-out line attempts:

// vals = new T[10]; // can't create an array of T

The reason you can’t create an array of T is that there is no way for the compiler to know what type of array to actually create.

However, you can pass a reference to a type-compatible array to Gen( ) when an object is created and assign that reference to vals, as the program does in this line:

vals = nums; // OK to assign reference to existent array

This works because the array passed to Gen has a known type, which will be the same type as T at the time of object creation.

Inside main( ), notice that you can’t declare an array of references to a specific generic type. That is, this line

// Gen\<Integer\>[] gens = new Gen\<Integer\>[10]; // Wrong!

won’t compile.

You can create an array of references to a generic type if you use a wildcard, however, as shown here:

Gen\<?\>[] gens = new Gen\<?\>[10]; // OK

This approach is better than using an array of raw types, because at least some type checking will still be enforced.

# Generic Exception Restriction

A generic class cannot extend Throwable. This means that you cannot create generic exception classes.