# I/O, Try-with-Resources, and Other Topics

This chapter introduces one of Java’s most important packages, java.io, which supports Java’s basic I/O (input/output) system, including file I/O. Support for I/O comes from Java’s core API libraries, not from language keywords. For this reason, an in-depth discussion of this topic is found in Part II of this book, which examines several of Java’s API packages. Here, the foundation of this important subsystem is introduced so that you can see how it fits into the larger context of the Java programming and execution environment. This chapter also examines the try-with-resources statement and several more Java keywords: transient, volatile, instanceof, native, strictfp, and assert. It concludes by discussing static import and describing another use for the this keyword.

# I/O Basics

As you may have noticed while reading the preceding 12 chapters, not much use has been made of I/O in the sample programs. In fact, aside from print( ) and println( ), none of the I/O methods have been used significantly. The reason is simple: Most real applications of Java are not text-based, console programs. Rather, they are either graphically oriented programs that rely on one of Java’s graphical user interface (GUI) frameworks, such as Swing, for user interaction, or they are web applications. Although text-based, console programs are excellent as teaching examples, they do not, as a general rule, constitute an important use for Java in the real world. Also, Java’s support for console I/O is limited and somewhat awkward to use—even in simple sample programs. Text-based console I/O is just not that useful in real-world Java programming.

The preceding paragraph notwithstanding, Java does provide strong, flexible support for I/O as it relates to files and networks. Java’s I/O system is cohesive and consistent. In fact, once you understand its fundamentals, the rest of the I/O system is easy to master. A general overview of I/O is presented here. A detailed description is found in Chapters 22 and 23.

# Streams

Java programs perform I/O through streams. A stream is an abstraction that either produces or consumes information. A stream is linked to a physical device by the Java I/O system. All streams behave in the same manner, even if the actual physical devices to which they are linked differ. Thus, the same I/O classes and methods can be applied to different types of devices. This means that an input stream can abstract many different kinds of input: from a disk file, a keyboard, or a network socket. Likewise, an output stream may refer to the console, a disk file, or a network connection. Streams are a clean way to deal with input/output without having every part of your code understand the difference between a keyboard and a network, for example. Java implements streams within class hierarchies defined in the java.io package.

NOTE In addition to the stream-based I/O defined in java.io, Java also provides buffer- and channel-based I/O, which are defined in java.nio and its subpackages. They are described in Chapter 23.

# Byte Streams and Character Streams

Java defines two types of I/O streams: byte and character. Byte streams provide a convenient means for handling input and output of bytes. Byte streams are used, for example, when reading or writing binary data. Character streams provide a convenient means for handling input and output of characters. They use Unicode and, therefore, can be internationalized. Also, in some cases, character streams are more efficient than byte streams.

The original version of Java (Java 1.0) did not include character streams and, thus, all I/O was byte-oriented. Character streams were added by Java 1.1, and certain byte-oriented classes and methods were deprecated. Although old code that doesn’t use character streams is becoming increasingly rare, it may still be encountered from time to time. As a general rule, old code should be updated to take advantage of character streams where appropriate.

One other point: At the lowest level, all I/O is still byte-oriented. The character-based streams simply provide a convenient and efficient means for handling characters.

An overview of both byte-oriented streams and character-oriented streams is presented in the following sections.

# The Byte Stream Classes

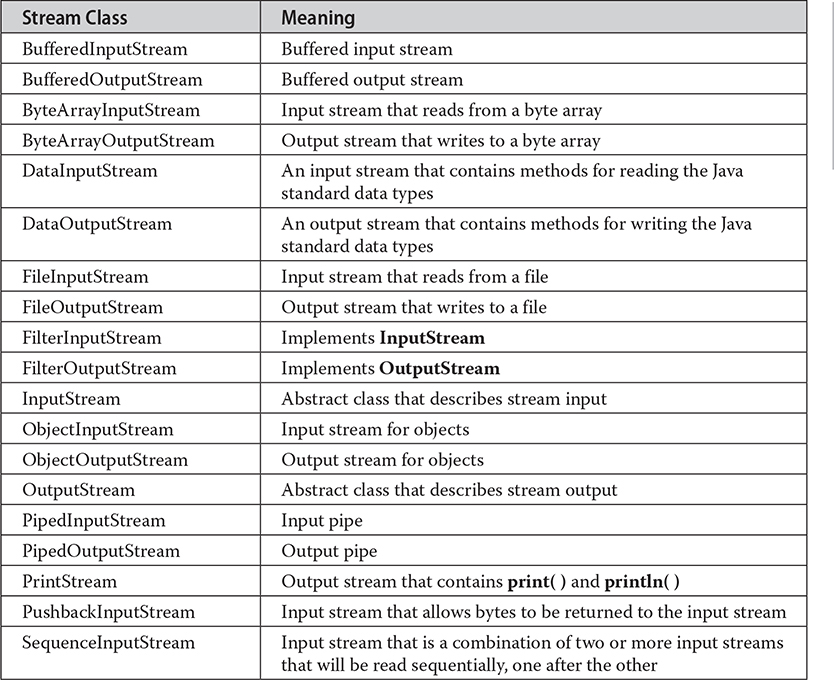

Byte streams are defined by using two class hierarchies. At the top are two abstract classes: InputStream and OutputStream. Each of these abstract classes has several concrete subclasses that handle the differences among various devices, such as disk files, network connections, and even memory buffers. The non-deprecated byte stream classes in java.io are shown in Table 13-1. A few of these classes are discussed later in this section. Others are described in Part II of this book. Remember, to use the stream classes, you must import java.io.

Table 13-1 The Non-Deprecated Byte Stream Classes in java.io

The abstract classes InputStream and OutputStream define several key methods that the other stream classes implement. Two of the most important are read( ) and write( ), which, respectively, read and write bytes of data. Each has a form that is abstract and must be overridden by derived stream classes.

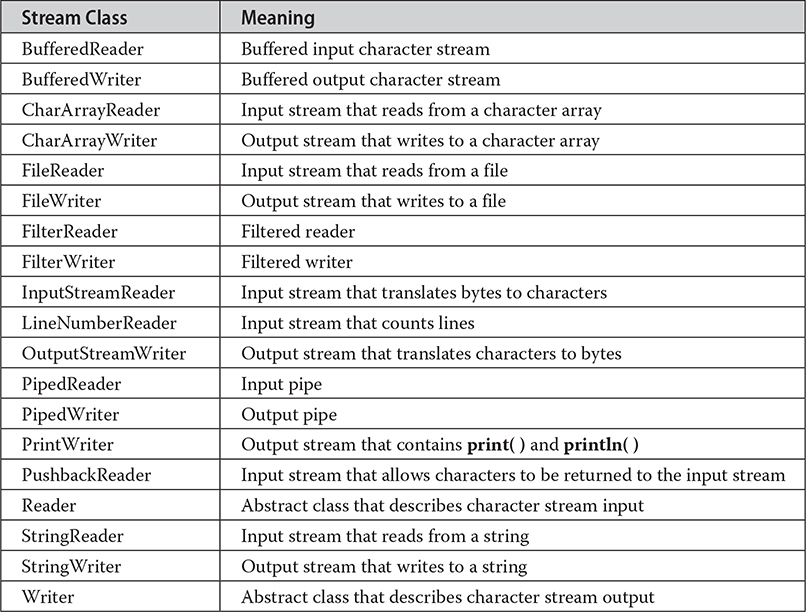

# The Character Stream Classes

Character streams are defined by using two class hierarchies. At the top are two abstract classes: Reader and Writer. These abstract classes handle Unicode character streams. Java has several concrete subclasses of each of these. The character stream classes in java.io are shown in Table 13-2.

Table 13-2 The Character Stream I/O Classes in java.io

The abstract classes Reader and Writer define several key methods that the other stream classes implement. Two of the most important methods are read( ) and write( ), which read and write characters of data, respectively. Each has a form that is abstract and must be overridden by derived stream classes.

# The Predefined Streams

As you know, all Java programs automatically import the java.lang package. This package defines a class called System, which encapsulates several aspects of the run-time environment. For example, using some of its methods, you can obtain the current time and the settings of various properties associated with the system. System also contains three predefined stream variables: in, out, and err. These fields are declared as public, static, and final within System. This means that they can be used by any other part of your program and without reference to a specific System object.

System.out refers to the standard output stream. By default, this is the console. System.in refers to standard input, which is the keyboard by default. System.err refers to the standard error stream, which also is the console by default. However, these streams may be redirected to any compatible I/O device.

System.in is an object of type InputStream; System.out and System.err are objects of type PrintStream. These are byte streams, even though they are typically used to read and write characters from and to the console. As you will see, you can wrap these within character-based streams, if desired.

The preceding chapters have been using System.out in their examples. You can use System.err in much the same way. As explained in the next section, use of System.in is a little more complicated.

# Reading Console Input

In the early days of Java, the only way to perform console input was to use a byte stream. Today, using a byte stream to read console input is still often acceptable, such as when used in sample programs. However, for commercial applications, the preferred method of reading console input is to use a character-oriented stream. This makes your program easier to internationalize and maintain.

In Java, console input is accomplished (either directly or indirectly) by reading from System.in. One way to obtain a character-based stream that is attached to the console is to wrap System.in in a BufferedReader. The BufferedReader class supports a buffered input stream. A commonly used constructor is shown here:

BufferedReader(Reader inputReader)

Here, inputReader is the stream that is linked to the instance of BufferedReader that is being created. Reader is an abstract class. One of its concrete subclasses is InputStreamReader, which converts bytes to characters.

Beginning with JDK 17, the precise way you obtain an InputStreamReader linked to System.in has changed. In the past, it was common to use the following InputStreamReader constructor for this purpose:

InputStreamReader(InputStream inputStream)

Because System.in refers to an object of type InputStream, it can be used for inputStream. Thus, the following line of code shows a common approach used in the past for creating a BufferedReader connected to the keyboard:

BufferedReader br = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in));

After this statement executes, br is a character-based stream that is linked to the console through System.in.

However, beginning with JDK 17, it is now recommended to explicitly specify the charset associated with the console when creating the InputStreamReader. A charset defines the way that bytes are mapped to characters. Normally, when a charset is not specified, the default charset of the JVM is used. However, in the case of the console, the charset used for console input may differ from this default charset. Thus, it is now recommended that this form of InputStreamReader constructor be used:

InputStreamReader(InputStream inputStream, Charset charset)

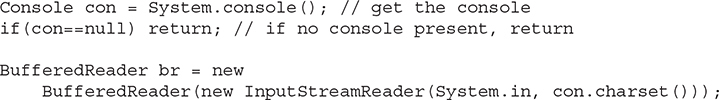

For charset, use the charset associated with the console. This charset is returned by charset( ), which is a new method added by JDK 17 to the Console class. (See Chapter 22.) You obtain a Console object by calling System.console( ). It returns a reference to the console, or null if no console is present. Therefore, today the following sequence shows one way to wrap System.in in a BufferedReader:

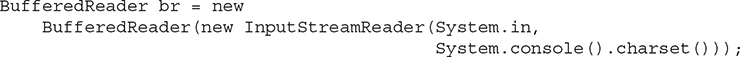

Of course, in cases in which you know that a console will be present, the sequence can be shortened to:

Because a console is (obviously) required to run the examples in this book, this is the form we will use.

One other point: It is also possible to obtain a Reader that is already associated with the console by use of the reader( ) method defined by Console. However, we will use the InputStreamReader approach as just described because it explicitly demonstrates the way that byte streams and character streams can interact.

# Reading Characters

To read a character from a BufferedReader, use read( ). The version of read( ) that we will be using is

int read( ) throws IOException

Each time that read( ) is called, it reads a character from the input stream and returns it as an integer value. It returns –1 when an attempt is made to read at the end of the stream. As you can see, it can throw an IOException.

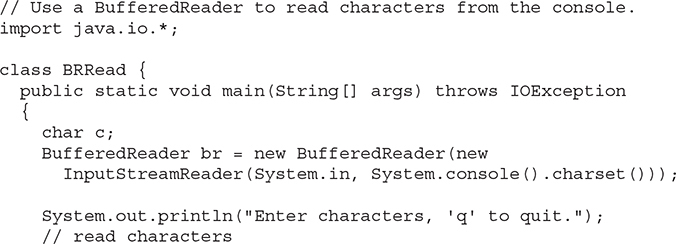

The following program demonstrates read( ) by reading characters from the console until the user types a "q." Notice that any I/O exceptions that might be generated are simply thrown out of main( ). Such an approach is common when reading from the console in simple sample programs such as those shown in this book, but in more sophisticated applications, you can handle the exceptions explicitly.

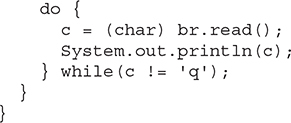

Here is a sample run:

This output may look a little different from what you expected because System.in is line buffered, by default. This means that no input is actually passed to the program until you press ENTER. As you can guess, this does not make read( ) particularly valuable for interactive console input.

# Reading Strings

To read a string from the keyboard, use the version of readLine( ) that is a member of the BufferedReader class. Its general form is shown here:

String readLine( ) throws IOException

As you can see, it returns a String object.

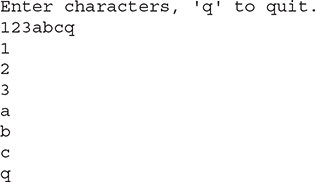

The following program demonstrates BufferedReader and the readLine( ) method; the program reads and displays lines of text until you enter the word "stop":

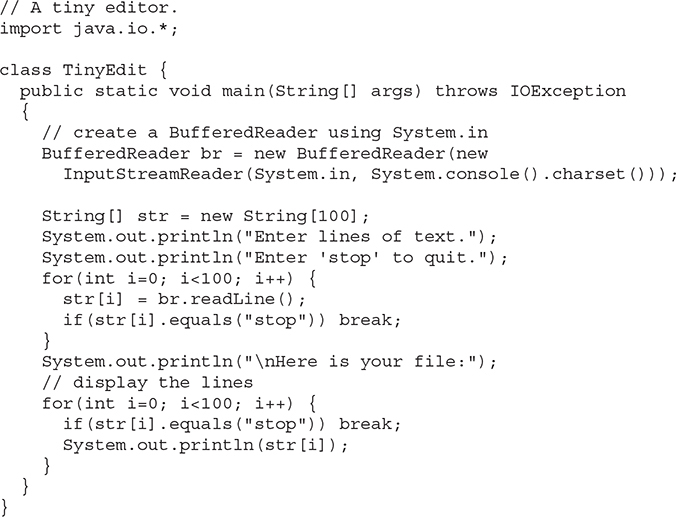

The next example creates a tiny text editor. It creates an array of String objects and then reads in lines of text, storing each line in the array. It will read up to 100 lines or until you enter "stop." It uses a BufferedReader to read from the console.

Here is a sample run:

# Writing Console Output

Console output is most easily accomplished with print( ) and println( ), described earlier, which are used in most of the examples in this book. These methods are defined by the class PrintStream (which is the type of object referenced by System.out). Even though System.out is a byte stream, using it for simple program output is still acceptable. However, a character-based alternative is described in the next section.

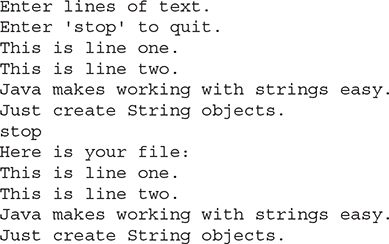

Because PrintStream is an output stream derived from OutputStream, it also implements the low-level method write( ). Thus, write( ) can be used to write to the console. The simplest form of write( ) defined by PrintStream is shown here:

void write(int byteval)

This method writes the byte specified by byteval. Although byteval is declared as an integer, only the low-order eight bits are written. Here is a short example that uses write( ) to output the character "A" followed by a newline to the screen:

You will not often use write( ) to perform console output (although doing so might be useful in some situations) because print( ) and println( ) are substantially easier to use.

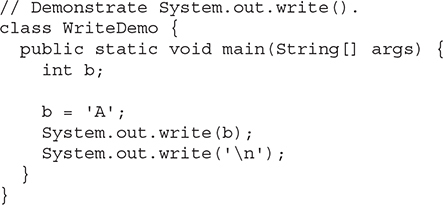

# The PrintWriter Class

Although using System.out to write to the console is acceptable, its use is probably best for debugging purposes or for sample programs, such as those found in this book. For real-world programs, the recommended method of writing to the console when using Java is through a PrintWriter stream. PrintWriter is one of the character-based classes. Using a character-based class for console output makes internationalizing your program easier.

PrintWriter defines several constructors. The one we will use is shown here:

PrintWriter(OutputStream outputStream, boolean flushingOn)

Here, outputStream is an object of type OutputStream, and flushingOn controls whether Java flushes the output stream every time a println( ) method (among others) is called. If flushingOn is true, flushing automatically takes place. If false, flushing is not automatic.

PrintWriter supports the print( ) and println( ) methods. Thus, you can use these methods in the same way as you used them with System.out. If an argument is not a simple type, the PrintWriter methods call the object’s toString( ) method and then display the result.

To write to the console by using a PrintWriter, specify System.out for the output stream and automatic flushing. For example, this line of code creates a PrintWriter that is connected to console output:

PrintWriter pw = new PrintWriter(System.out, true);

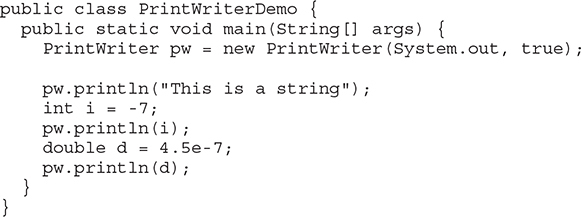

The following application illustrates using a PrintWriter to handle console output:

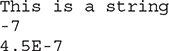

The output from this program is shown here:

Remember, there is nothing wrong with using System.out to write simple text output to the console when you are learning Java or debugging your programs. However, using a PrintWriter makes your real-world applications easier to internationalize. Because no advantage is gained by using a PrintWriter in the sample programs shown in this book, we will continue to use System.out to write to the console.

# Reading and Writing Files

Java provides a number of classes and methods that allow you to read and write files. Before we begin, it is important to state that the topic of file I/O is quite large, and file I/O is examined in detail in Part II. The purpose of this section is to introduce the basic techniques that read from and write to a file. Although byte streams are used, these techniques can be adapted to the character-based streams.

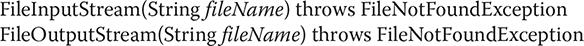

Two of the most often-used stream classes are FileInputStream and FileOutputStream, which create byte streams linked to files. To open a file, you simply create an object of one of these classes, specifying the name of the file as an argument to the constructor. Although both classes support additional constructors, the following are the forms that we will be using:

Here, fileName specifies the name of the file that you want to open. When you create an input stream, if the file does not exist, then FileNotFoundException is thrown. For output streams, if the file cannot be opened or created, then FileNotFoundException is thrown. FileNotFoundException is a subclass of IOException. When an output file is opened, any preexisting file by the same name is destroyed.

NOTE In situations in which a security manager is present, several of the file classes, including FileInputStream and FileOutputStream, will throw a SecurityException if a security violation occurs when attempting to open a file. By default, applications run via java do not use a security manager. For that reason, the I/O examples in this book do not need to watch for a possible SecurityException. However, other types of applications may use the security manager, and file I/O performed by such an application could generate a SecurityException. In that case, you will need to appropriately handle this exception. Be aware that JDK 17 deprecates the security manager for removal.

When you are done with a file, you must close it. This is done by calling the close( ) method, which is implemented by both FileInputStream and FileOutputStream. It is shown here:

void close( ) throws IOException

Closing a file releases the system resources allocated to the file, allowing them to be used by another file. Failure to close a file can result in “memory leaks” because of unused resources remaining allocated.

NOTE The close( ) method is specified by the AutoCloseable interface in java.lang. AutoCloseable is inherited by the Closeable interface in java.io. Both interfaces are implemented by the stream classes, including FileInputStream and FileOutputStream.

Before moving on, it is important to point out that there are two basic approaches that you can use to close a file when you are done with it. The first is the traditional approach, in which close( ) is called explicitly when the file is no longer needed. This is the approach used by all versions of Java prior to JDK 7 and is, therefore, found in all pre-JDK 7 legacy code. The second is to use the try-with-resources statement added by JDK 7, which automatically closes a file when it is no longer needed. In this approach, no explicit call to close( ) is executed. Since you may still encounter pre-JDK 7 legacy code, it is important that you know and understand the traditional approach. Furthermore, the traditional approach could still be the best approach in some situations. Therefore, we will begin with it. The automated approach is described in the following section.

To read from a file, you can use a version of read( ) that is defined within FileInputStream. The one that we will use is shown here:

int read( ) throws IOException

Each time that it is called, it reads a single byte from the file and returns the byte as an integer value. read( ) returns –1 when an attempt is made to read at the end of the stream. It can throw an IOException.

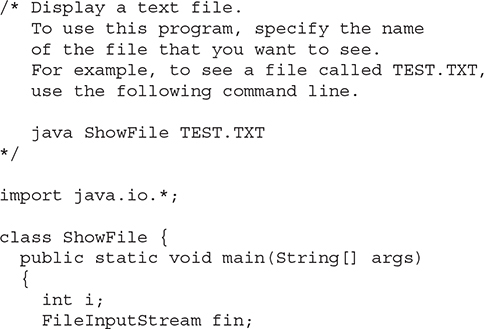

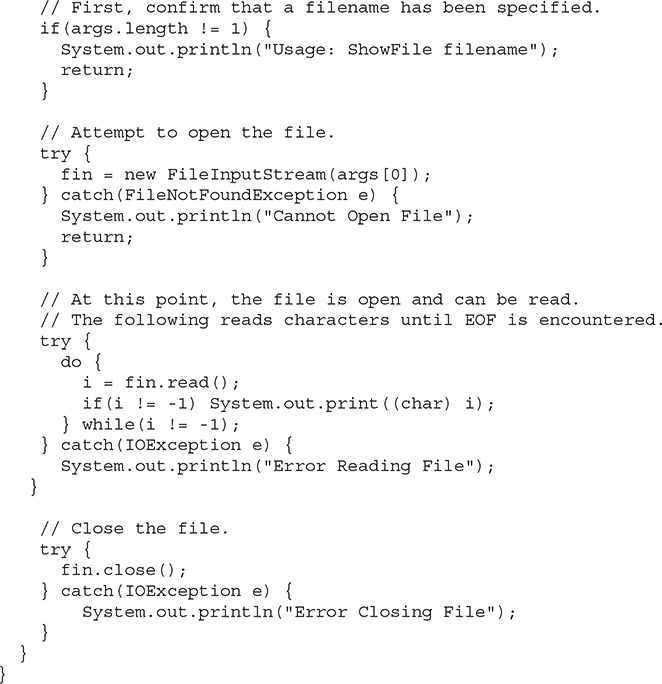

The following program uses read( ) to input and display the contents of a file that contains ASCII text. The name of the file is specified as a command-line argument.

In the program, notice the try/catch blocks that handle the I/O errors that might occur. Each I/O operation is monitored for exceptions, and if an exception occurs, it is handled. Be aware that in simple programs or sample code, it is common to see I/O exceptions simply thrown out of main( ), as was done in the earlier console I/O examples. Also, in some real-world code, it can be helpful to let an exception propagate to a calling routine to let the caller know that an I/O operation failed. However, most of the file I/O examples in this book handle all I/O exceptions explicitly, as shown, for the sake of illustration.

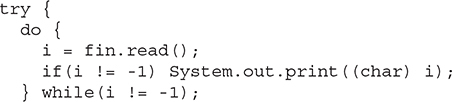

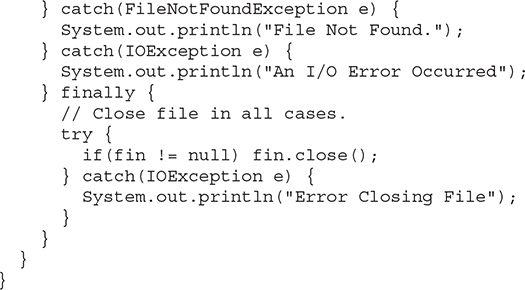

Although the preceding example closes the file stream after the file is read, there is a variation that is often useful. The variation is to call close( ) within a finally block. In this approach, all of the methods that access the file are contained within a try block, and the finally block is used to close the file. This way, no matter how the try block terminates, the file is closed. Assuming the preceding example, here is how the try block that reads the file can be recoded:

Although not an issue in this case, one advantage to this approach in general is that if the code that accesses a file terminates because of some non-I/O related exception, the file is still closed by the finally block.

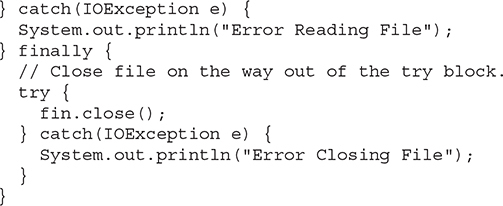

Sometimes it’s easier to wrap the portions of a program that open the file and access the file within a single try block (rather than separating the two) and then use a finally block to close the file. For example, here is another way to write the ShowFile program:

In this approach, notice that fin is initialized to null. Then, in the finally block, the file is closed only if fin is not null. This works because fin will be non-null only if the file is successfully opened. Thus, close( ) is not called if an exception occurs while opening the file.

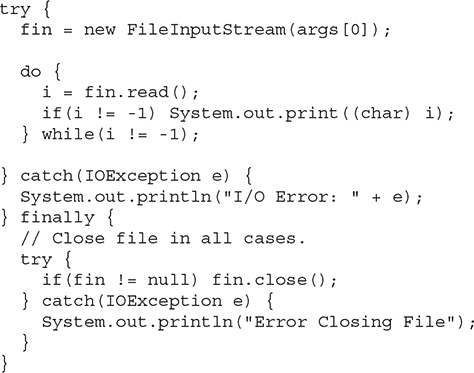

It is possible to make the try/catch sequence in the preceding example a bit more compact. Because FileNotFoundException is a subclass of IOException, it need not be caught separately. For example, here is the sequence recoded to eliminate catching FileNotFoundException. In this case, the standard exception message, which describes the error, is displayed.

In this approach, any error, including an error opening the file, is simply handled by the single catch statement. Because of its compactness, this approach is used by many of the I/O examples in this book. Be aware, however, that this approach is not appropriate in cases in which you want to deal separately with a failure to open a file, such as might be caused if a user mistypes a filename. In such a situation, you might want to prompt for the correct name, for example, before entering a try block that accesses the file.

To write to a file, you can use the write( ) method defined by FileOutputStream. Its simplest form is shown here:

void write(int byteval) throws IOException

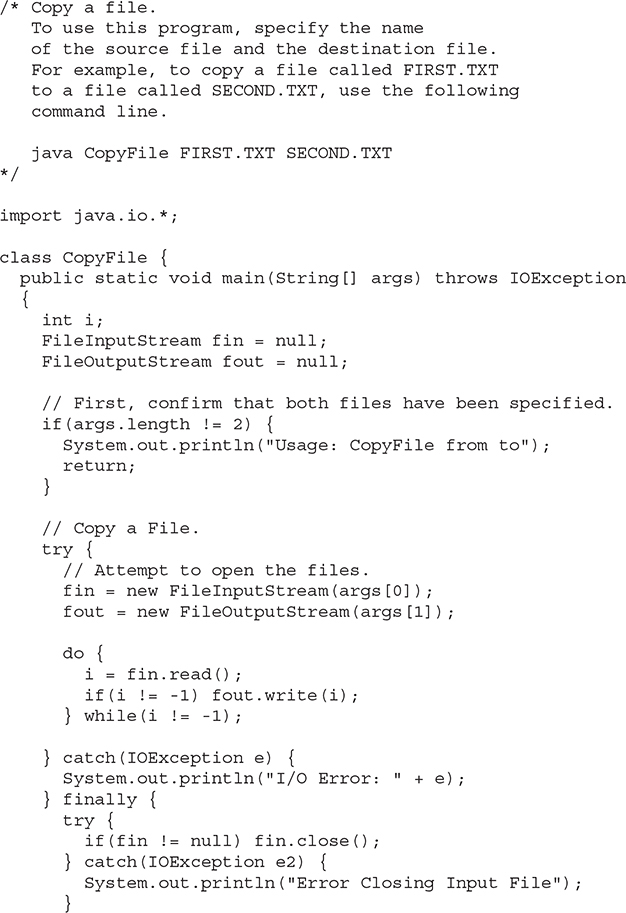

This method writes the byte specified by byteval to the file. Although byteval is declared as an integer, only the low-order eight bits are written to the file. If an error occurs during writing, an IOException is thrown. The next example uses write( ) to copy a file:

In the program, notice that two separate try blocks are used when closing the files. This ensures that both files are closed, even if the call to fin.close( ) throws an exception.

In general, notice that all potential I/O errors are handled in the preceding two programs by the use of exceptions. This differs from some computer languages that use error codes to report file errors. Not only do exceptions make file handling cleaner, but they also enable Java to easily differentiate the end-of-file condition from file errors when input is being performed.

# Automatically Closing a File

In the preceding section, the sample programs have made explicit calls to close( ) to close a file once it is no longer needed. As mentioned, this is the way files were closed when using versions of Java prior to JDK 7. Although this approach is still valid and useful, JDK 7 added a feature that offers another way to manage resources, such as file streams, by automating the closing process. This feature, sometimes referred to as automatic resource management, or ARM for short, is based on an expanded version of the try statement. The principal advantage of automatic resource management is that it prevents situations in which a file (or other resource) is inadvertently not released after it is no longer needed. As explained, forgetting to close a file can result in memory leaks and could lead to other problems.

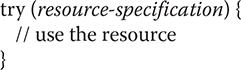

Automatic resource management is based on an expanded form of the try statement. Here is its general form:

Typically, resource-specification is a statement that declares and initializes a resource, such as a file stream. It consists of a variable declaration in which the variable is initialized with a reference to the object being managed. When the try block ends, the resource is automatically released. In the case of a file, this means that the file is automatically closed. (Thus, there is no need to call close( ) explicitly.) Of course, this form of try can also include catch and finally clauses. This form of try is called the try-with-resources statement.

NOTE Beginning with JDK 9, it is also possible for the resource specification of the try to consist of a variable that has been declared and initialized earlier in the program. However, that variable must be effectively final, which means that it has not been assigned a new value after being given its initial value.

The try-with-resources statement can be used only with those resources that implement the AutoCloseable interface defined by java.lang. This interface defines the close( ) method. AutoCloseable is inherited by the Closeable interface in java.io. Both interfaces are implemented by the stream classes. Thus, try-with-resources can be used when working with streams, including file streams.

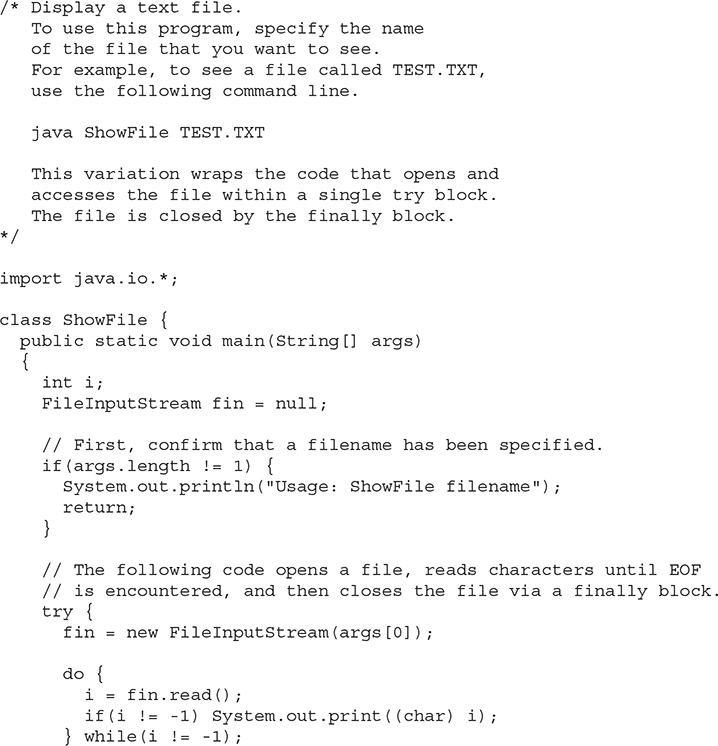

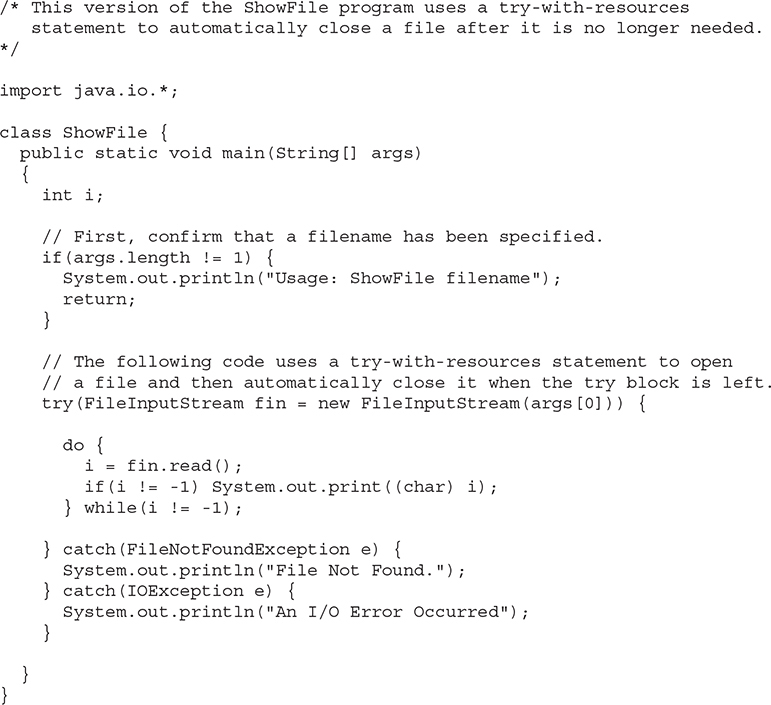

As a first example of automatically closing a file, here is a reworked version of the ShowFile program that uses it:

In the program, pay special attention to how the file is opened within the try statement:

try(FileInputStream fin = new FileInputStream(args[0])) {

Notice how the resource-specification portion of the try declares a FileInputStream called fin, which is then assigned a reference to the file opened by its constructor. Thus, in this version of the program, the variable fin is local to the try block, being created when the try is entered. When the try is left, the stream associated with fin is automatically closed by an implicit call to close( ). You don’t need to call close( ) explicitly, which means that you can’t forget to close the file. This is a key advantage of using try-with-resources.

It is important to understand that a resource declared in the try statement is implicitly final. This means that you can’t assign to the resource after it has been created. Also, the scope of the resource is limited to the try-with-resources statement.

Before moving on, it is useful to mention that beginning with JDK 10, you can use local variable type inference to specify the type of the resource declared in a try-with-resources statement. To do so, specify the type as var. When this is done, the type of the resource is inferred from its initializer. For example, the try statement in the preceding program can now be written like this:

try(var fin = new FileInputStream(args[0])) {

Here, fin is inferred to be of type FileInputStream because that is the type of its initializer. Because a number of readers will be working in Java environments that predate JDK 10, the try-with-resource statements in the remainder of this book will not make use of type inference so that the code works for as many readers as possible. Of course, going forward, you should consider using type inference in your own code.

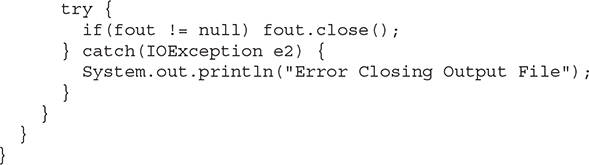

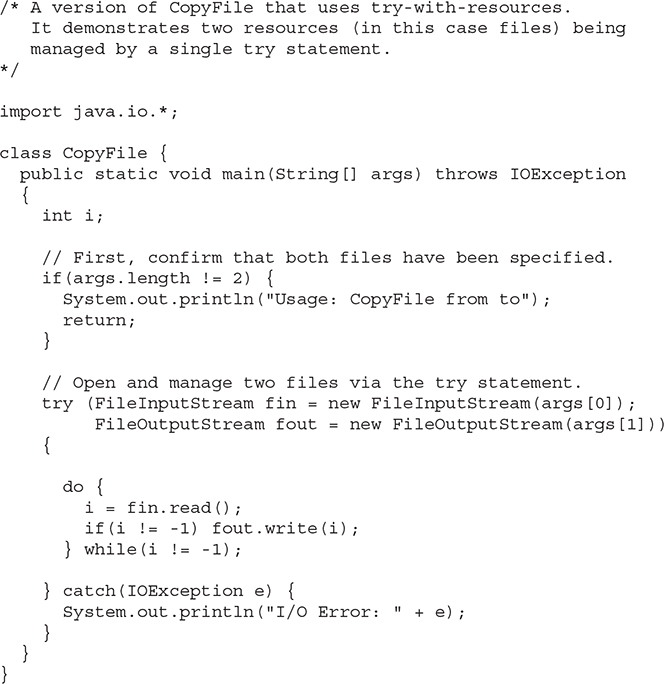

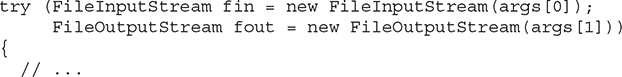

You can manage more than one resource within a single try statement. To do so, simply separate each resource specification with a semicolon. The following program shows an example. It reworks the CopyFile program shown earlier so that it uses a single try-with-resources statement to manage both fin and fout.

In this program, notice how the input and output files are opened within the try block:

After this try block ends, both fin and fout will have been closed. If you compare this version of the program to the previous version, you will see that it is much shorter. The ability to streamline source code is a side-benefit of automatic resource management.

There is one other aspect to try-with-resources that needs to be mentioned. In general, when a try block executes, it is possible that an exception inside the try block will lead to another exception that occurs when the resource is closed in a finally clause. In the case of a “normal” try statement, the original exception is lost, being preempted by the second exception. However, when using try-with-resources, the second exception is suppressed. It is not, however, lost. Instead, it is added to the list of suppressed exceptions associated with the first exception. The list of suppressed exceptions can be obtained by using the getSuppressed( ) method defined by Throwable.

Because of the benefits that the try-with-resources statement offers, it will be used by many, but not all, of the sample programs in this edition of this book. Some of the examples will still use the traditional approach to closing a resource. There are several reasons for this. First, you may encounter legacy code that still relies on the traditional approach. It is important that all Java programmers be fully versed in, and comfortable with, the traditional approach when maintaining this older code. Second, it is possible that some programmers will continue to work in a pre-JDK 7 environment for a period of time. In such situations, the expanded form of try is not available. Finally, there may be cases in which explicitly closing a resource is more appropriate than the automated approach. For these reasons, some of the examples in this book will continue to use the traditional approach, explicitly calling close( ). In addition to illustrating the traditional technique, these examples can also be compiled and run by all readers in all environments.

REMEMBER A few examples in this book use the traditional approach to closing files as a means of illustrating this technique, which is widely used in legacy code. However, for new code, you will usually want to use the automated approach supported by the try-with-resources statement just described.

# The transient and volatile Modifiers

Java defines two interesting type modifiers: transient and volatile. These modifiers are used to handle somewhat specialized situations.

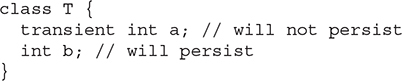

When an instance variable is declared as transient, its value need not persist when an object is stored. For example:

Here, if an object of type T is written to a persistent storage area, the contents of a would not be saved, but the contents of b would.

The volatile modifier tells the compiler that the variable modified by volatile can be changed unexpectedly by other parts of your program. One of these situations involves multithreaded programs. In a multithreaded program, sometimes two or more threads share the same variable. For efficiency considerations, each thread can keep its own, private copy of such a shared variable. The real (or master) copy of the variable is updated at various times, such as when a synchronized method is entered. While this approach works fine, it may be inefficient at times. In some cases, all that really matters is that the master copy of a variable always reflects its current state. To ensure this, simply specify the variable as volatile, which tells the compiler that it must always use the master copy of a volatile variable (or, at least, always keep any private copies up to date with the master copy, and vice versa). Also, accesses to the shared variable must be executed in the precise order indicated by the program.

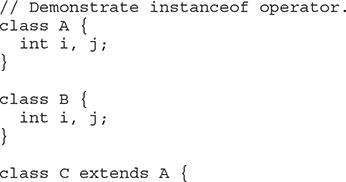

# Introducing instanceof

Sometimes, knowing the type of an object during run time is useful. For example, you might have one thread of execution that generates various types of objects, and another thread that processes these objects. In this situation, it might be useful for the processing thread to know the type of each object when it receives it. Another situation in which knowledge of an object’s type at run time is important involves casting. In Java, an invalid cast causes a run-time error. Many invalid casts can be caught at compile time. However, casts involving class hierarchies can produce invalid casts that can be detected only at run time. For example, a superclass called A can produce two subclasses, called B and C. Thus, casting a B object into type A or casting a C object into type A is legal, but casting a B object into type C (or vice versa) isn’t legal. Because an object of type A can refer to objects of either B or C, how can you know, at run time, what type of object is actually being referred to before attempting the cast to type C? It could be an object of type A, B, or C. If it is an object of type B, a run-time exception will be thrown. Java provides the run-time operator instanceof to answer this question.

Before we begin, it is necessary to state that instanceof was significantly enhanced by JDK 17 with a powerful new feature based on pattern matching. Here, the traditional form of instanceof is introduced. The enhanced form is covered in Chapter 17.

The traditional instanceof operator has this general form:

objref instanceof type

Here, objref is a reference to an instance of a class, and type is a class type. If objref is of the specified type or can be cast into the specified type, then the instanceof operator evaluates to true. Otherwise, its result is false. Thus, instanceof is the means by which your program can obtain run-time type information about an object.

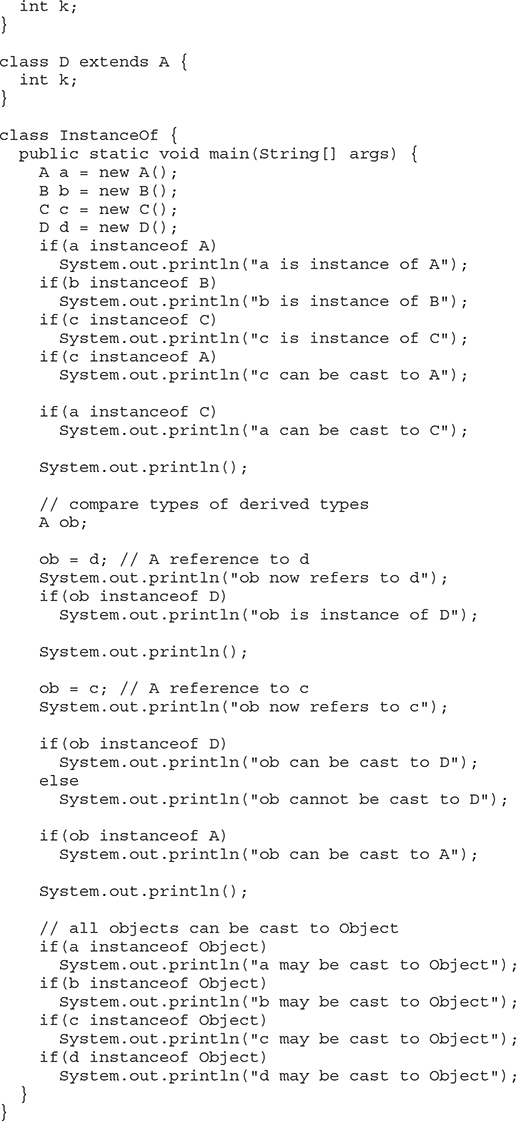

The following program demonstrates instanceof:

The output from this program is shown here:

The instanceof operator isn’t needed by most simple programs because, often, you know the type of object with which you are working. However, it can be very useful when you’re writing generalized routines that operate on objects of a complex class hierarchy or that are created from code outside your direct control. As you will see, the pattern matching enhancements described in Chapter 17 streamline its use.

# strictfp

With the creation of Java 2 several years ago, the floating-point computation model was relaxed slightly. Specifically, the new model did not require the truncation of certain intermediate values that occur during a computation. This prevented overflow or underflow in some cases. By modifying a class, a method, or interface with strictfp, you could ensure that floating-point calculations (and thus all truncations) took place precisely as they did in earlier versions of Java. When a class was modified by strictfp, all the methods in the class were also modified by strictfp automatically. However, beginning with JDK 17, all floating-point computations are now strict, and strictfp is obsolete and no longer required. Its use will now generate a warning message.

For versions of Java prior to JDK 17, the following example illustrates strictfp. It tells Java to use the original floating-point model for calculations in all methods defined within MyClass:

strictfp class MyClass { //...

Frankly, most programmers never needed to use strictfp because it affected only a very small class of problems.

REMEMBER Beginning with JDK 17, stricfp has been rendered obsolete and its use will now generate a warning message.

# Native Methods

Although it is rare, occasionally you may want to call a subroutine that is written in a language other than Java. Typically, such a subroutine exists as executable code for the CPU and environment in which you are working—that is, native code. For example, you may want to call a native code subroutine to achieve faster execution time. Or, you may want to use a specialized, third-party library, such as a statistical package. However, because Java programs are compiled to bytecode, which is then interpreted (or compiled on the fly) by the Java run-time system, it would seem impossible to call a native code subroutine from within your Java program. Fortunately, this conclusion is false. Java provides the native keyword, which is used to declare native code methods. Once declared, these methods can be called from inside your Java program just as you call any other Java method.

To declare a native method, precede the method with the native modifier, but do not define any body for the method. For example:

public native int meth() ;

After you declare a native method, you must write the native method and follow a rather complex series of steps to link it with your Java code. Consult the Java documentation for current details.

NOTE JDK 21 introduces a more sophisticated API for using code libraries written in languages other than Java code. The new java.lang.foreign.* package contains an API that gives greater control over managing memory and calling functions in such libraries.

# Using assert

Another interesting keyword is assert. It is used during program development to create an assertion, which is a condition that should be true during the execution of the program. For example, you might have a method that should always return a positive integer value. You might test this by asserting that the return value is greater than zero using an assert statement. At run time, if the condition is true, no other action takes place. However, if the condition is false, then an AssertionError is thrown. Assertions are often used during testing to verify that some expected condition is actually met. They are not usually used for released code.

The assert keyword has two forms. The first is shown here:

assert condition;

Here, condition is an expression that must evaluate to a Boolean result. If the result is true, then the assertion is true and no other action takes place. If the condition is false, then the assertion fails and a default AssertionError object is thrown.

The second form of assert is shown here:

assert condition: expr ;

In this version, expr is a value that is passed to the AssertionError constructor. This value is converted to its string format and displayed if an assertion fails. Typically, you will specify a string for expr, but any non-void expression is allowed as long as it defines a reasonable string conversion.

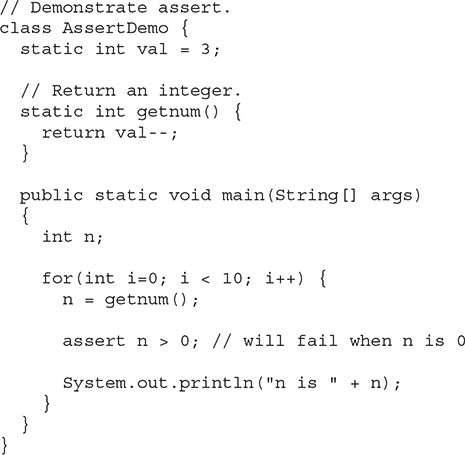

Here is an example that uses assert. It verifies that the return value of getnum( ) is positive.

To enable assertion checking at run time, you must specify the -ea option. For example, to enable assertions for AssertDemo, execute it using this line:

java -ea AssertDemo

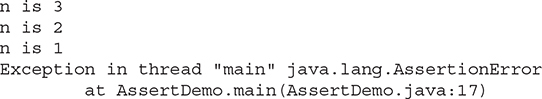

After compiling and running as just described, the program creates the following output:

In main( ), repeated calls are made to the method getnum( ), which returns an integer value. The return value of getnum( ) is assigned to n and then tested using this assert statement:

assert n > 0; // will fail when n is 0

This statement will fail when n equals 0, which it will after the fourth call. When this happens, an exception is thrown.

As explained, you can specify the message displayed when an assertion fails. For example, if you substitute

assert n > 0 : "n is not positive!";

for the assertion in the preceding program, then the following output will be generated:

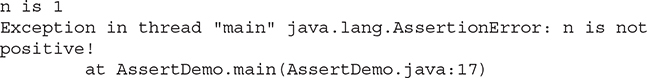

One important point to understand about assertions is that you must not rely on them to perform any action actually required by the program. The reason is that normally, released code will be run with assertions disabled. For example, consider this variation of the preceding program:

In this version of the program, the call to getnum( ) is moved inside the assert statement. Although this works fine if assertions are enabled, it will cause a malfunction when assertions are disabled because the call to getnum( ) will never be executed! In fact, n must now be initialized because the compiler will recognize that it might not be assigned a value by the assert statement.

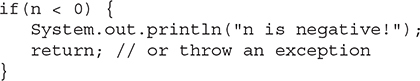

Assertions can be quite useful because they streamline the type of error checking that is common during development. For example, prior to assert, if you wanted to verify that n was positive in the preceding program, you had to use a sequence of code similar to this:

With assert, you need only one line of code. Furthermore, you don’t have to remove the assert statements from your released code.

# Assertion Enabling and Disabling Options

When executing code, you can disable all assertions by using the -da option. You can enable or disable a specific package (and all of its subpackages) by specifying its name followed by three periods after the -ea or -da option. For example, to enable assertions in a package called MyPack, use

-ea:MyPack...

To disable assertions in MyPack, use

-da:MyPack...

You can also specify a class with the -ea or -da option. For example, this enables AssertDemo individually:

-ea:AssertDemo

# Static Import

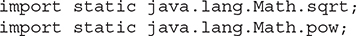

Java includes a feature called static import that expands the capabilities of the import keyword. By following import with the keyword static, an import statement can be used to import the static members of a class or interface. When using static import, it is possible to refer to static members directly by their names, without having to qualify them with the name of their class. This simplifies and shortens the syntax required to use a static member.

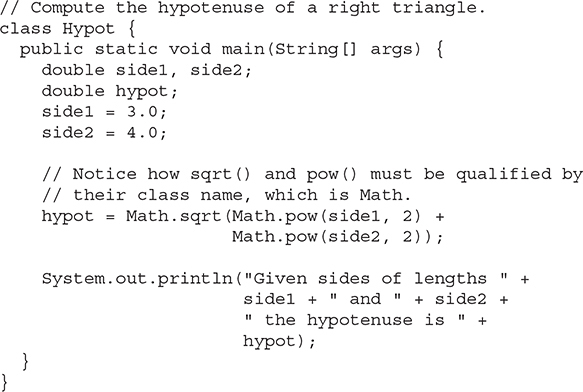

To understand the usefulness of static import, let’s begin with an example that does not use it. The following program computes the hypotenuse of a right triangle. It uses two static methods from Java’s built-in math class Math, which is part of java.lang. The first is Math.pow( ), which returns a value raised to a specified power. The second is Math.sqrt( ), which returns the square root of its argument.

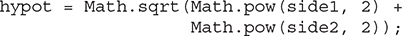

Because pow( ) and sqrt( ) are static methods, they must be called through the use of their class’s name, Math. This results in a somewhat unwieldy hypotenuse calculation:

As this simple example illustrates, having to specify the class name each time pow( ) or sqrt( ) (or any of Java’s other math methods, such as sin( ), cos( ), and tan( )) is used can grow tedious.

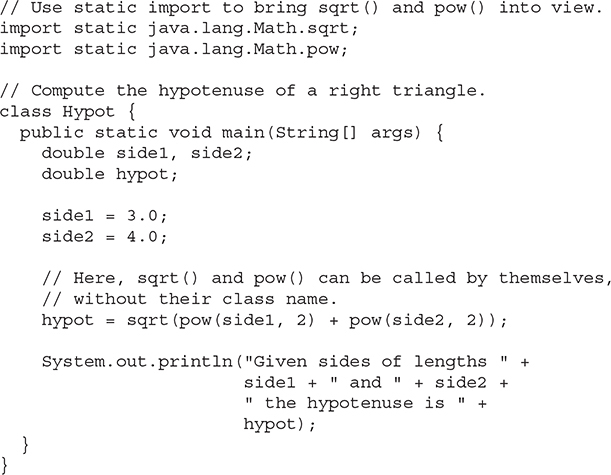

You can eliminate the tedium of specifying the class name through the use of static import, as shown in the following version of the preceding program:

In this version, the names sqrt and pow are brought into view by these static import statements:

After these statements, it is no longer necessary to qualify sqrt( ) or pow( ) with their class name. Therefore, the hypotenuse calculation can more conveniently be specified, as shown here:

hypot = sqrt(pow(side1, 2) + pow(side2, 2));

As you can see, this form is considerably more readable.

There are two general forms of the import static statement. The first, which is used by the preceding example, brings into view a single name. Its general form is shown here:

import static pkg.type-name.static-member-name ;

Here, type-name is the name of a class or interface that contains the desired static member. Its full package name is specified by pkg. The name of the member is specified by static-member-name.

The second form of static import imports all static members of a given class or interface. Its general form is shown here:

import static pkg.type-name.*;

If you will be using many static methods or fields defined by a class, then this form lets you bring them into view without having to specify each individually. Therefore, the preceding program could have used this single import statement to bring both pow( ) and sqrt( ) (and all other static members of Math ) into view:

import static java.lang.Math.*;

Of course, static import is not limited just to the Math class or just to methods. For example, this brings the static field System.out into view:

import static java.lang.System.out;

After this statement, you can output to the console without having to qualify out with System, as shown here:

out.println("After importing System.out, you can use out directly.");

Whether importing System.out as just shown is a good idea is subject to debate. Although it does shorten the statement, it is no longer instantly clear to anyone reading the program that the out being referred to is System.out.

One other point: in addition to importing the static members of classes and interfaces defined by the Java API, you can also use static import to import the static members of classes and interfaces that you create.

As convenient as static import can be, it is important not to abuse it. Remember, the reason that Java organizes its libraries into packages is to avoid namespace collisions. When you import static members, you are bringing those members into the current namespace. Thus, you are increasing the potential for namespace conflicts and inadvertent name hiding. If you are using a static member once or twice in the program, it’s best not to import it. Also, some static names, such as System.out, are so recognizable that you might not want to import them. Static import is designed for those situations in which you are using a static member repeatedly, such as when performing a series of mathematical computations. In essence, you should use, but not abuse, this feature.

# Invoking Overloaded Constructors Through this( )

When working with overloaded constructors, it is sometimes useful for one constructor to invoke another. In Java, this is accomplished by using another form of the this keyword. The general form is shown here:

this(arg-list)

When this( ) is executed, the overloaded constructor that matches the parameter list specified by arg-list is executed first. Then, if there are any statements inside the original constructor, they are executed. The call to this( ) must be the first statement within the constructor.

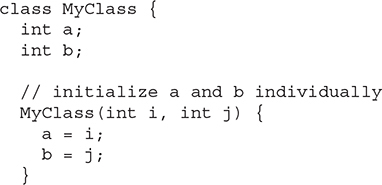

To understand how this( ) can be used, let’s work through a short example. First, consider the following class that does not use this( ):

This class contains three constructors, each of which initializes the values of a and b. The first is passed individual values for a and b. The second is passed just one value, which is assigned to both a and b. The third gives a and b default values of zero.

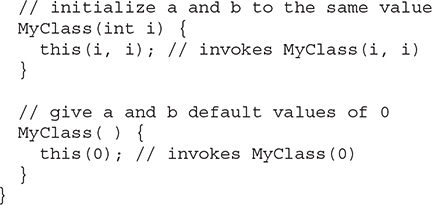

By using this( ), it is possible to rewrite MyClass as shown here:

In this version of MyClass, the only constructor that actually assigns values to the a and b fields is MyClass(int, int). The other two constructors simply invoke that constructor (either directly or indirectly) through this( ). For example, consider what happens when this statement executes:

MyClass mc = new MyClass(8);

The call to MyClass(8) causes this(8, 8) to be executed, which translates into a call to MyClass(8, 8), because this is the version of the MyClass constructor whose parameter list matches the arguments passed via this( ). Now, consider the following statement, which uses the default constructor:

MyClass mc2 = new MyClass();

In this case, this(0) is called. This causes MyClass(0) to be invoked because it is the constructor with the matching parameter list. Of course, MyClass(0) then calls MyClass(0,0) as just described.

One reason why invoking overloaded constructors through this( ) can be useful is that it can prevent the unnecessary duplication of code. In many cases, reducing duplicate code decreases the time it takes to load your class because often the object code is smaller. This is especially important for programs delivered via the Internet in which load times are an issue. Using this( ) can also help structure your code when constructors contain a large amount of duplicate code.

However, you need to be careful. Constructors that call this( ) will execute a bit slower than those that contain all of their initialization code inline. This is because the call and return mechanism used when the second constructor is invoked adds overhead. If your class will be used to create only a handful of objects, or if the constructors in the class that call this( ) will be seldom used, then this decrease in run-time performance is probably insignificant. However, if your class will be used to create a large number of objects (on the order of thousands) during program execution, then the negative impact of the increased overhead could be meaningful. Because object creation affects all users of your class, there will be cases in which you must carefully weigh the benefits of faster load time against the increased time it takes to create an object.

Here is another consideration: for very short constructors, such as those used by MyClass, there is often little difference in the size of the object code whether this( ) is used or not. (Actually, there are cases in which no reduction in the size of the object code is achieved.) This is because the bytecode that sets up and returns from the call to this( ) adds instructions to the object file. Therefore, in these types of situations, even though duplicate code is eliminated, using this( ) will not obtain significant savings in terms of load time. However, the added cost in terms of overhead to each object’s construction will still be incurred. Therefore, this( ) is most applicable to constructors that contain large amounts of initialization code, not those that simply set the value of a handful of fields.

There are two restrictions you need to keep in mind when using this( ). First, you cannot use any instance variable of the constructor’s class in a call to this( ). Second, you cannot use super( ) and this( ) in the same constructor because each must be the first statement in the constructor.

# A Word About Value-Based Classes

Beginning with JDK 8, Java has included the concept of a value-based class, and a number of classes in the Java API have been classified as value-based. Value-based classes are defined by various rules and restrictions. Here are some examples. They must be final, and their instance variables must also be final. If equals( ) determines that two instances of a value-based class are equal, one instance can be used in place of the other. Also, two equal but separately obtained instances of a value-based class may, in fact, be the same object. Very importantly, you should avoid using instances of a value-based class for synchronization. Additional rules and restrictions apply. Furthermore, the definition of value-based classes has evolved somewhat over time. Consult the Java documentation for the latest details on value-based classes, including which classes in the API library are documented as value-based.