# Lambda Expressions

During Java’s ongoing development and evolution, many features have been added since its original 1.0 release. However, two stand out because they have profoundly reshaped the language, fundamentally changing the way that code is written. The first was the addition of generics, added by JDK 5. (See Chapter 14.) The second is the lambda expression, which is the subject of this chapter.

Added by JDK 8, lambda expressions (and their related features) significantly enhanced Java because of two primary reasons. First, they added new syntax elements that increased the expressive power of the language. In the process, they streamlined the way that certain common constructs are implemented. Second, the addition of lambda expressions resulted in new capabilities being incorporated into the API library. Among these new capabilities are the ability to more easily take advantage of the parallel processing capabilities of multicore environments, especially as it relates to the handling of for-each style operations, and the new stream API, which supports pipeline operations on data. The addition of lambda expressions also provided the catalyst for other new Java features, including the default method (described in Chapter 9), which lets you define default behavior for an interface method, and the method reference (described here), which lets you refer to a method without executing it.

In the final analysis, in much the same way that generics reshaped Java several years ago, lambda expressions continue to reshape Java today. Simply put, lambda expressions will impact virtually all Java programmers. They truly are that important.

# Introducing Lambda Expressions

Key to understanding Java’s implementation of lambda expressions are two constructs. The first is the lambda expression itself. The second is the functional interface. Let’s begin with a simple definition of each.

A lambda expression is, essentially, an anonymous (that is, unnamed) method. However, this method is not executed on its own. Instead, it is used to implement a method defined by a functional interface. Thus, a lambda expression results in a form of anonymous class. Lambda expressions are also commonly referred to as closures.

A functional interface is an interface that contains one and only one abstract method. Normally, this method specifies the intended purpose of the interface. Thus, a functional interface typically represents a single action. For example, the standard interface Runnable is a functional interface because it defines only one method: run( ). Therefore, run( ) defines the action of Runnable. Furthermore, a functional interface defines the target type of a lambda expression. Here is a key point: a lambda expression can be used only in a context in which its target type is specified. One other thing: a functional interface is sometimes referred to as a SAM type, where SAM stands for Single Abstract Method.

NOTE A functional interface may specify any public method defined by Object, such as equals( ), without affecting its “functional interface” status. The public Object methods are considered implicit members of a functional interface because they are automatically implemented by an instance of a functional interface.

Let’s now look more closely at both lambda expressions and functional interfaces.

# Lambda Expression Fundamentals

The lambda expression introduced a new syntax element and operator into the Java language. The new operator, sometimes referred to as the lambda operator or the arrow operator, is −>. It divides a lambda expression into two parts. The left side specifies any parameters required by the lambda expression. (If no parameters are needed, an empty parameter list is used.) On the right side is the lambda body, which specifies the actions of the lambda expression. The −> can be verbalized as “becomes” or “goes to.”

Java defines two types of lambda bodies. One consists of a single expression, and the other type consists of a block of code. We will begin with lambdas that define a single expression. Lambdas with block bodies are discussed later in this chapter.

At this point, it will be helpful to look at a few examples of lambda expressions before continuing. Let’s begin with what is probably the simplest type of lambda expression you can write. It evaluates to a constant value and is shown here:

() -> 123.45

This lambda expression takes no parameters; thus, the parameter list is empty. It returns the constant value 123.45. Therefore, it is similar to the following method:

double myMeth() { return 123.45; }

Of course, the method defined by a lambda expression does not have a name.

A slightly more interesting lambda expression is shown here:

() -> Math.random() * 100

This lambda expression obtains a pseudo-random value from Math.random( ), multiplies it by 100, and returns the result. It, too, does not require a parameter.

When a lambda expression requires a parameter, it is specified in the parameter list on the left side of the lambda operator. Here is a simple example:

(n) -> (n % 2)==0

This lambda expression returns true if the value of parameter n is even. Although it is possible to explicitly specify the type of a parameter, such as n in this case, often you won’t need to do so because in many cases its type can be inferred. Like a named method, a lambda expression can specify as many parameters as needed.

# Functional Interfaces

As stated, a functional interface is an interface that specifies only one abstract method. If you have been programming in Java for some time, you might at first think that all interface methods are implicitly abstract. Although this was true prior to JDK 8, the situation has changed. As explained in Chapter 9, beginning with JDK 8, it is possible to specify a default implementation for a method declared in an interface. Private and static interface methods also supply an implementation. As a result, today, an interface method is abstract only if it does not specify an implementation. Because non-default, non-static, non-private interface methods are implicitly abstract, there is no need to use the abstract modifier (although you can specify it, if you like).

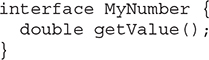

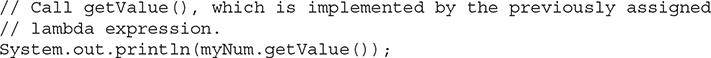

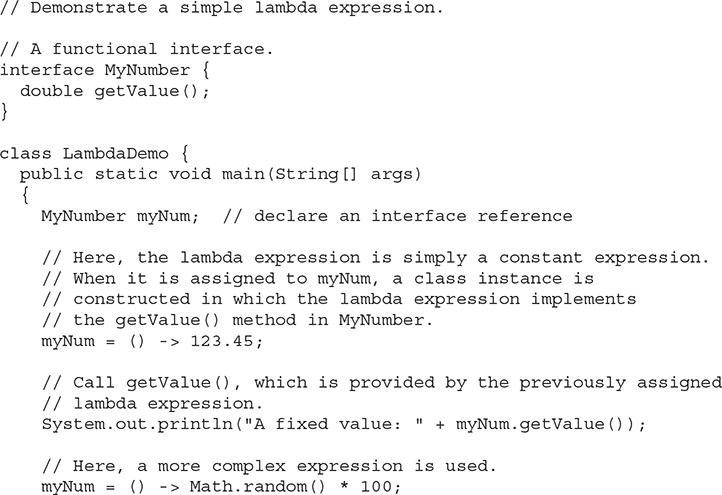

Here is an example of a functional interface:

In this case, the method getValue( ) is implicitly abstract, and it is the only method defined by MyNumber. Thus, MyNumber is a functional interface, and its function is defined by getValue( ).

As mentioned earlier, a lambda expression is not executed on its own. Rather, it forms the implementation of the abstract method defined by the functional interface that specifies its target type. As a result, a lambda expression can be specified only in a context in which a target type is defined. One of these contexts is created when a lambda expression is assigned to a functional interface reference. Other target type contexts include variable initialization, return statements, and method arguments, to name a few.

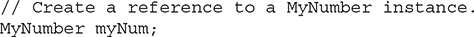

Let’s work through an example that shows how a lambda expression can be used in an assignment context. First, a reference to the functional interface MyNumber is declared:

Next, a lambda expression is assigned to that interface reference:

When a lambda expression occurs in a target type context, an instance of a class is automatically created that implements the functional interface, with the lambda expression defining the behavior of the abstract method declared by the functional interface. When that method is called through the target, the lambda expression is executed. Thus, a lambda expression gives us a way to transform a code segment into an object.

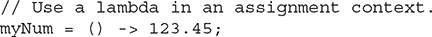

In the preceding example, the lambda expression becomes the implementation for the getValue( ) method. As a result, the following displays the value 123.45:

Because the lambda expression assigned to myNum returns the value 123.45, that is the value obtained when getValue( ) is called.

In order for a lambda expression to be used in a target type context, the type of the abstract method and the type of the lambda expression must be compatible. For example, if the abstract method specifies two int parameters, then the lambda must specify two parameters whose type either is explicitly int or can be implicitly inferred as int by the context. In general, the type and number of the lambda expression’s parameters must be compatible with the method’s parameters; the return types must be compatible; and any exceptions thrown by the lambda expression must be acceptable to the method.

# Some Lambda Expression Examples

With the preceding discussion in mind, let’s look at some simple examples that illustrate the basic lambda expression concepts. The first example puts together the pieces shown in the foregoing section.

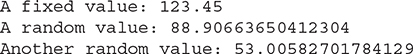

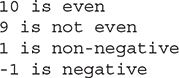

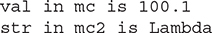

Sample output from the program is shown here:

As mentioned, the lambda expression must be compatible with the abstract method that it is intended to implement. For this reason, the commented-out line at the end of the preceding program is illegal because a value of type String is not compatible with double, which is the return type required by getValue( ).

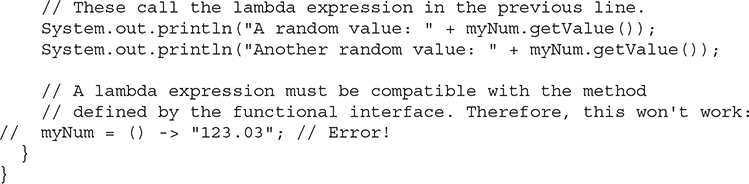

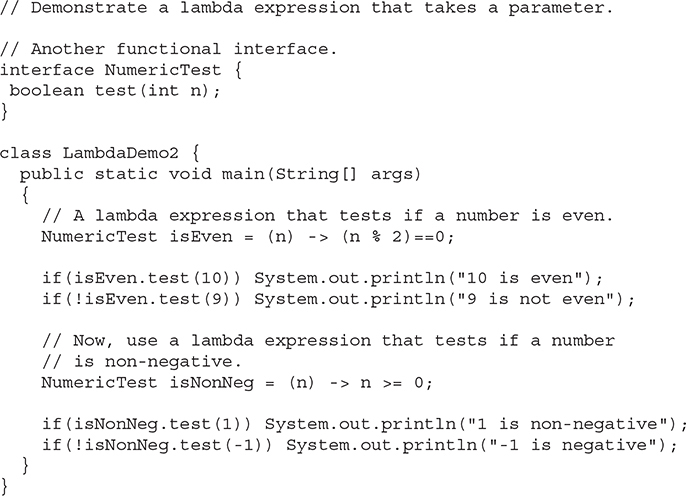

The next example shows the use of a parameter with a lambda expression:

The output from this program is shown here:

This program demonstrates a key fact about lambda expressions that warrants close examination. Pay special attention to the lambda expression that performs the test for evenness. It is shown again here:

(n) -> (n % 2)==0

Notice that the type of n is not specified. Rather, its type is inferred from the context. In this case, its type is inferred from the parameter type of test( ) as defined by the NumericTest interface, which is int. It is also possible to explicitly specify the type of a parameter in a lambda expression. For example, this is also a valid way to write the preceding:

(int n) -> (n % 2)==0

Here, n is explicitly specified as int. Usually it is not necessary to explicitly specify the type, but you can in those situations that require it. Beginning with JDK 11, you can also use var to explicitly indicate local variable type inference for a lambda expression parameter.

This program demonstrates another important point about lambda expressions: A functional interface reference can be used to execute any lambda expression that is compatible with it. Notice that the program defines two different lambda expressions that are compatible with the test( ) method of the functional interface NumericTest. The first, called isEven, determines if a value is even. The second, called isNonNeg, checks if a value is non-negative. In each case, the value of the parameter n is tested. Because each lambda expression is compatible with test( ), each can be executed through a NumericTest reference.

One other point before moving on: When a lambda expression has only one parameter, it is not necessary to surround the parameter name with parentheses when it is specified on the left side of the lambda operator. For example, this is also a valid way to write the lambda expression used in the program:

n -> (n % 2)==0

For consistency, this book will surround all lambda expression parameter lists with parentheses, even those containing only one parameter. Of course, you are free to adopt a different style.

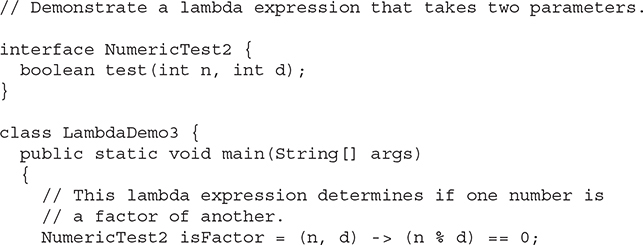

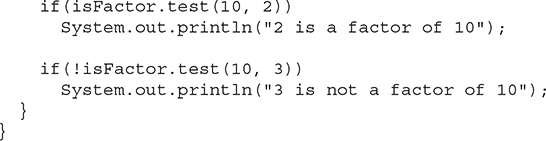

The next program demonstrates a lambda expression that takes two parameters. In this case, the lambda expression tests if one number is a factor of another.

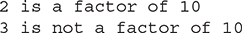

The output is shown here:

In this program, the functional interface NumericTest2 defines the test( ) method:

boolean test(int n, int d);

In this version, test( ) specifies two parameters. Thus, for a lambda expression to be compatible with test( ), the lambda expression must also specify two parameters. Notice how they are specified:

(n, d) -> (n % d) == 0

The two parameters, n and d, are specified in the parameter list, separated by commas. This example can be generalized. Whenever more than one parameter is required, the parameters are specified, separated by commas, in a parenthesized list on the left side of the lambda operator.

Here is an important point about multiple parameters in a lambda expression: If you need to explicitly declare the type of a parameter, then all of the parameters must have declared types. For example, this is legal:

(int n, int d) -> (n % d) == 0

But this is not:

(int n, d) -> (n % d) == 0

# Block Lambda Expressions

The body of the lambdas shown in the preceding examples consist of a single expression. These types of lambda bodies are referred to as expression bodies, and lambdas that have expression bodies are sometimes called expression lambdas. In an expression body, the code on the right side of the lambda operator must consist of a single expression. While expression lambdas are quite useful, sometimes the situation will require more than a single expression. To handle such cases, Java supports a second type of lambda expression in which the code on the right side of the lambda operator consists of a block of code that can contain more than one statement. This type of lambda body is called a block body. Lambdas that have block bodies are sometimes referred to as block lambdas.

A block lambda expands the types of operations that can be handled within a lambda expression because it allows the body of the lambda to contain multiple statements. For example, in a block lambda you can declare variables, use loops, specify if and switch statements, create nested blocks, and so on. A block lambda is easy to create. Simply enclose the body within braces as you would any other block of statements.

Aside from allowing multiple statements, block lambdas are used much like the expression lambdas just discussed. One key difference, however, is that you must explicitly use a return statement to return a value. This is necessary because a block lambda body does not represent a single expression.

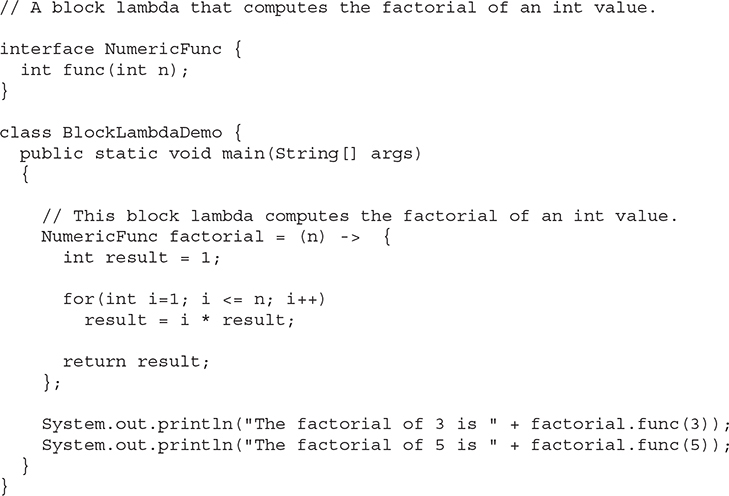

Here is an example that uses a block lambda to compute and return the factorial of an int value:

The output is shown here:

In the program, notice that the block lambda declares a variable called result, uses a for loop, and has a return statement. These are legal inside a block lambda body. In essence, the block body of a lambda is similar to a method body. One other point: When a return statement occurs within a lambda expression, it simply causes a return from the lambda. It does not cause an enclosing method to return.

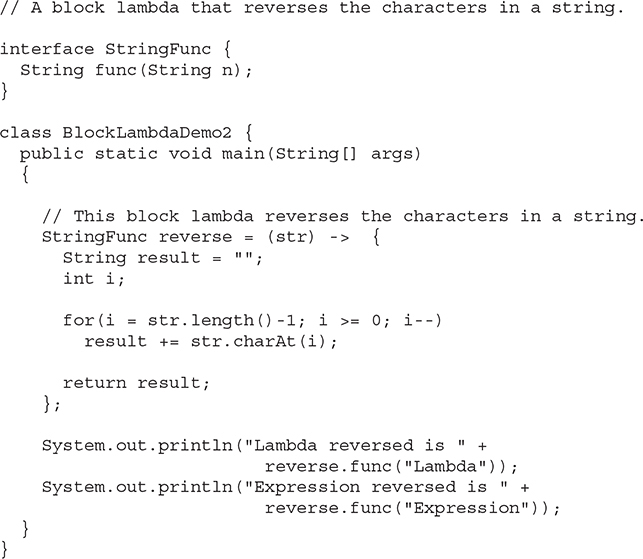

Another example of a block lambda is shown in the following program. It reverses the characters in a string.

The output is shown here:

In this example, the functional interface StringFunc declares the func( ) method. This method takes a parameter of type String and has a return type of String. Thus, in the reverse lambda expression, the type of str is inferred to be String. Notice that the charAt( ) method is called on str. This is legal because of the inference that str is of type String.

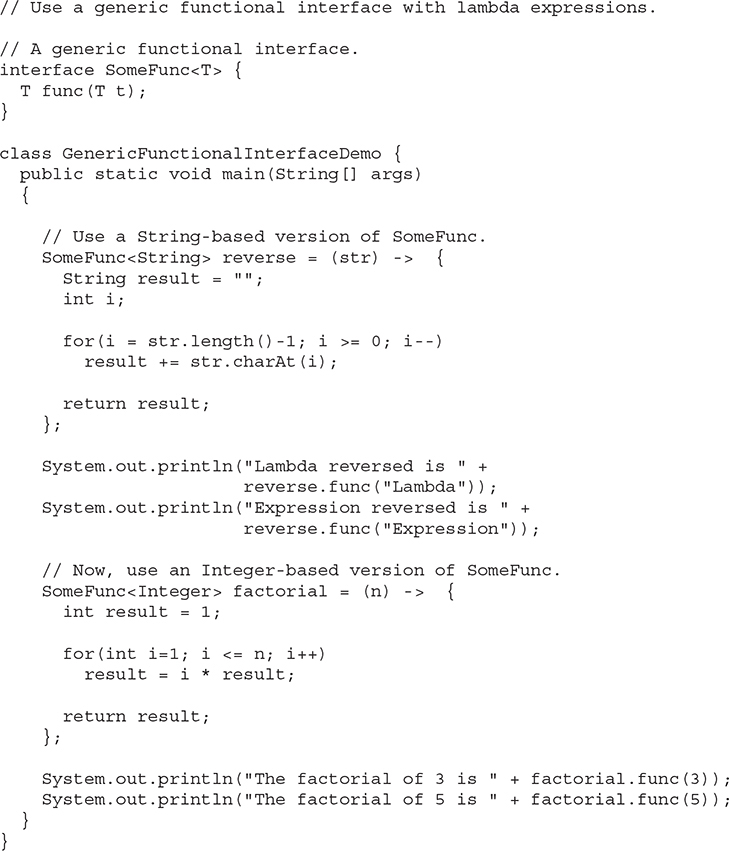

# Generic Functional Interfaces

A lambda expression itself cannot specify type parameters. Thus, a lambda expression cannot be generic. (Of course, because of type inference, all lambda expressions exhibit some “generic-like” qualities.) However, the functional interface associated with a lambda expression can be generic. In this case, the target type of the lambda expression is determined, in part, by the type argument or arguments specified when a functional interface reference is declared.

To understand the value of generic functional interfaces, consider this: The two examples in the previous section used two different functional interfaces, one called NumericFunc and the other called StringFunc. However, both defined a method called func( ) that took one parameter and returned a result. In the first case, the type of the parameter and return type was int. In the second case, the parameter and return type was String. Thus, the only difference between the two methods was the type of data they required. Instead of having two functional interfaces whose methods differ only in their data types, it is possible to declare one generic interface that can be used to handle both circumstances. The following program shows this approach:

The output is shown here:

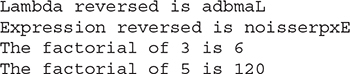

In the program, the generic functional interface SomeFunc is declared as shown here:

Here, T specifies both the return type and the parameter type of func( ). This means that it is compatible with any lambda expression that takes one parameter and returns a value of the same type.

The SomeFunc interface is used to provide a reference to two different types of lambdas. The first uses type String. The second uses type Integer. Thus, the same functional interface can be used to refer to the reverse lambda and the factorial lambda. Only the type argument passed to SomeFunc differs.

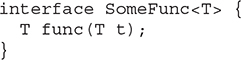

# Passing Lambda Expressions as Arguments

As explained earlier, a lambda expression can be used in any context that provides a target type. One of these is when a lambda expression is passed as an argument. In fact, passing a lambda expression as an argument is a common use of lambdas. Moreover, it is a very powerful use because it gives you a way to pass executable code as an argument to a method. This greatly enhances the expressive power of Java.

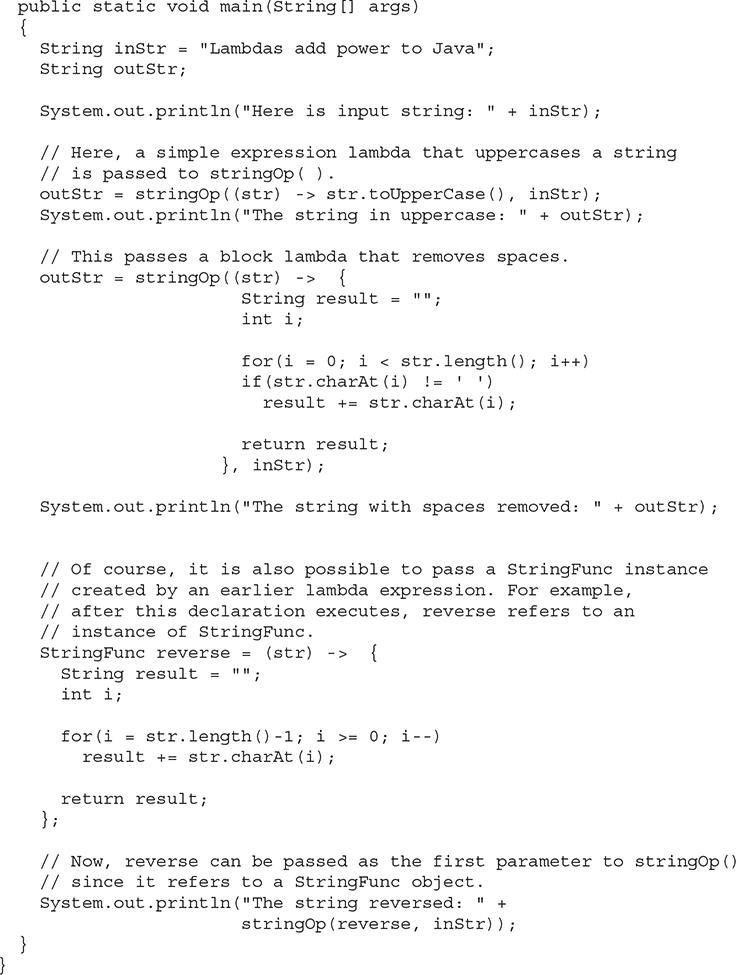

To pass a lambda expression as an argument, the type of the parameter receiving the lambda expression argument must be of a functional interface type compatible with the lambda. Although using a lambda expression as an argument is straightforward, it is still helpful to see it in action. The following program demonstrates the process:

The output is shown here:

In the program, first notice the stringOp( ) method. It has two parameters. The first is of type StringFunc, which is a functional interface. Thus, this parameter can receive a reference to any instance of StringFunc, including one created by a lambda expression. The second argument of stringOp( ) is of type String, and this is the string operated on.

Next, notice the first call to stringOp( ), shown again here:

outStr = stringOp((str) -> str.toUpperCase(), inStr);

Here, a simple expression lambda is passed as an argument. When this occurs, an instance of the functional interface StringFunc is created and a reference to that object is passed to the first parameter of stringOp( ). Thus, the lambda code, embedded in a class instance, is passed to the method. The target type context is determined by the type of parameter. Because the lambda expression is compatible with that type, the call is valid. Embedding simple lambdas, such as the one just shown, inside a method call is often a convenient technique—especially when the lambda expression is intended for a single use.

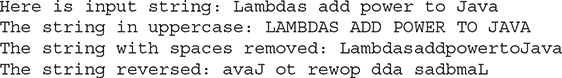

Next, the program passes a block lambda to stringOp( ). This lambda removes spaces from a string. It is shown again here:

Although this uses a block lambda, the process of passing the lambda expression is the same as just described for the simple expression lambda. In this case, however, some programmers will find the syntax a bit awkward.

When a block lambda seems overly long to embed in a method call, it is an easy matter to assign that lambda to a functional interface variable, as the previous examples have done. Then, you can simply pass that reference to the method. This technique is shown at the end of the program. There, a block lambda is defined that reverses a string. This lambda is assigned to reverse, which is a reference to a StringFunc instance. Thus, reverse can be used as an argument to the first parameter of stringOp( ). The program then calls stringOp( ), passing in reverse and the string on which to operate. Because the instance obtained by the evaluation of each lambda expression is an implementation of StringFunc, each can be used as the first parameter to stringOp( ).

One last point: In addition to variable initialization, assignment, and argument passing, the following also constitute target type contexts: casts, the ? operator, array initializers, return statements, and lambda expressions themselves.

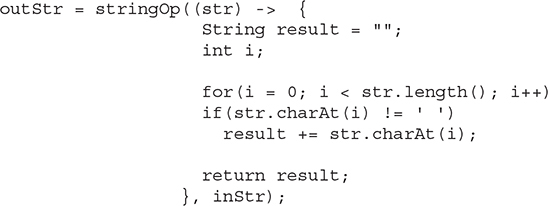

# Lambda Expressions and Exceptions

A lambda expression can throw an exception. However, it if throws a checked exception, then that exception must be compatible with the exception(s) listed in the throws clause of the abstract method in the functional interface. Here is an example that illustrates this fact. It computes the average of an array of double values. If a zero-length array is passed, however, it throws the custom exception EmptyArrayException. As the example shows, this exception is listed in the throws clause of func( ) declared inside the DoubleNumericArrayFunc functional interface.

The first call to average.func( ) returns the value 2.5. The second call, which passes a zero-length array, causes an EmptyArrayException to be thrown. Remember, the inclusion of the throws clause in func( ) is necessary. Without it, the program will not compile because the lambda expression will no longer be compatible with func( ).

This example demonstrates another important point about lambda expressions. Notice that the parameter specified by func( ) in the functional interface DoubleNumericArrayFunc is an array. However, the parameter to the lambda expression is simply n, rather than n[ ]. Remember, the type of a lambda expression parameter will be inferred from the target context. In this case, the target context is double[ ], so the type of n will be double[ ]. It is not necessary (or legal) to specify it as n[ ]. It would be legal to explicitly declare it as double[ ] n, but doing so gains nothing in this case.

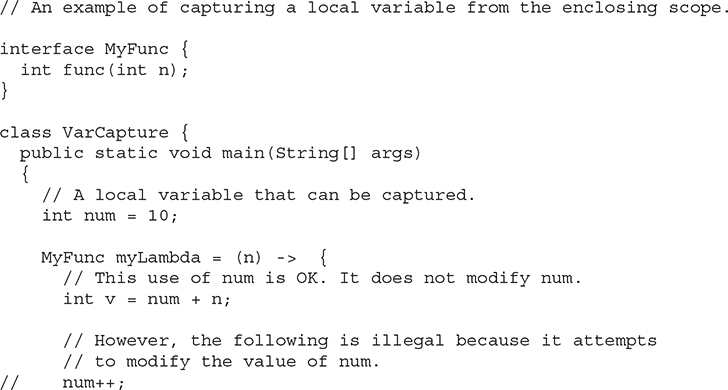

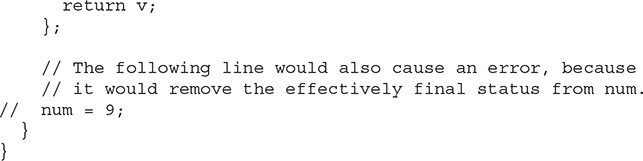

# Lambda Expressions and Variable Capture

Variables defined by the enclosing scope of a lambda expression are accessible within the lambda expression. For example, a lambda expression can use an instance or static variable defined by its enclosing class. A lambda expression also has access to this (both explicitly and implicitly), which refers to the invoking instance of the lambda expression’s enclosing class. Thus, a lambda expression can obtain or set the value of an instance or static variable and call a method defined by its enclosing class.

However, when a lambda expression uses a local variable from its enclosing scope, a special situation is created that is referred to as a variable capture. In this case, a lambda expression may only use local variables that are effectively final. An effectively final variable is one whose value does not change after it is first assigned. There is no need to explicitly declare such a variable as final, although doing so would not be an error. (The this parameter of an enclosing scope is automatically effectively final, and lambda expressions do not have a this of their own.)

It is important to understand that a local variable of the enclosing scope cannot be modified by the lambda expression. Doing so would remove its effectively final status, thus rendering it illegal for capture.

The following program illustrates the difference between effectively final and mutable local variables:

As the comments indicate, num is effectively final and can, therefore, be used inside myLambda. However, if num were to be modified, either inside the lambda or outside of it, num would lose its effectively final status. This would cause an error, and the program would not compile.

It is important to emphasize that a lambda expression can use and modify an instance variable from its invoking class. It just can’t use a local variable of its enclosing scope unless that variable is effectively final.

# Method References

There is an important feature related to lambda expressions called the method reference. A method reference provides a way to refer to a method without executing it. It relates to lambda expressions because it, too, requires a target type context that consists of a compatible functional interface. When evaluated, a method reference also creates an instance of the functional interface.

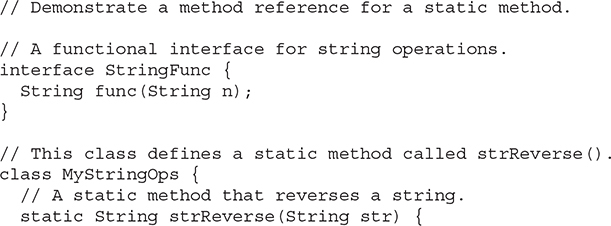

There are different types of method references. We will begin with method references to static methods.

# Method References to static Methods

To create a static method reference, use this general syntax:

ClassName::methodName

Notice that the class name is separated from the method name by a double colon. The :: is a separator that was added to Java by JDK 8 expressly for this purpose. This method reference can be used anywhere in which it is compatible with its target type.

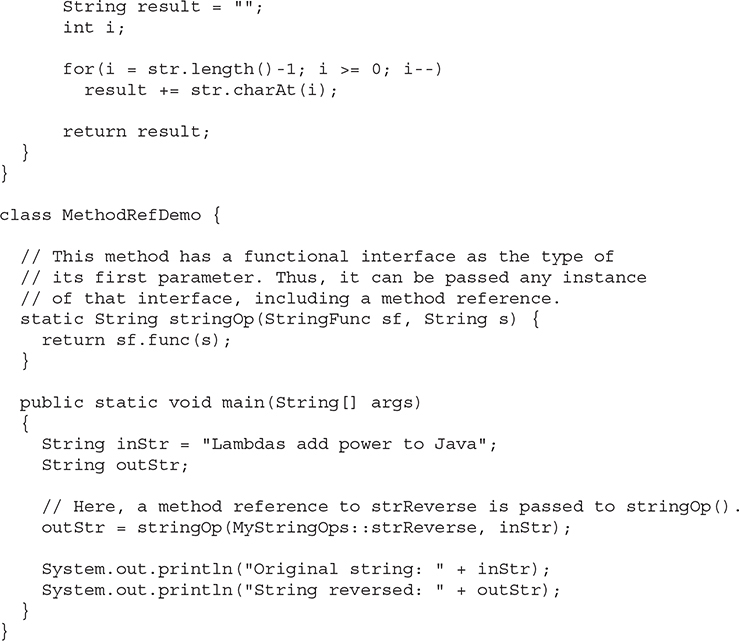

The following program demonstrates a static method reference:

The output is shown here:

In the program, pay special attention to this line:

outStr = stringOp(MyStringOps::strReverse, inStr);

Here, a reference to the static method strReverse( ), declared inside MyStringOps, is passed as the first argument to stringOp( ). This works because strReverse is compatible with the StringFunc functional interface. Thus, the expression MyStringOps::strReverse evaluates to a reference to an object in which strReverse provides the implementation of func( ) in StringFunc.

# Method References to Instance Methods

To pass a reference to an instance method on a specific object, use this basic syntax:

objRef::methodName

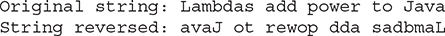

As you can see, the syntax is similar to that used for a static method, except that an object reference is used instead of a class name. Here is the previous program rewritten to use an instance method reference:

This program produces the same output as the previous version.

In the program, notice that strReverse( ) is now an instance method of MyStringOps. Inside main( ), an instance of MyStringOps called strOps is created. This instance is used to create the method reference to strReverse in the call to stringOp, as shown again here:

outStr = stringOp(strOps::strReverse, inStr);

In this example, strReverse( ) is called on the strOps object.

It is also possible to handle a situation in which you want to specify an instance method that can be used with any object of a given class—not just a specified object. In this case, you will create a method reference as shown here:

ClassName::instanceMethodName

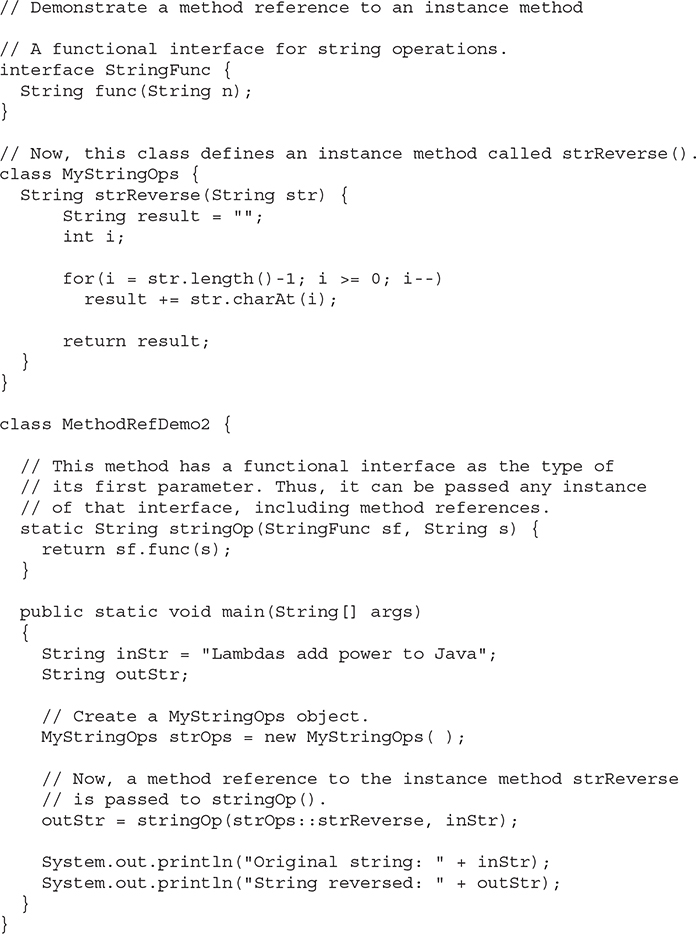

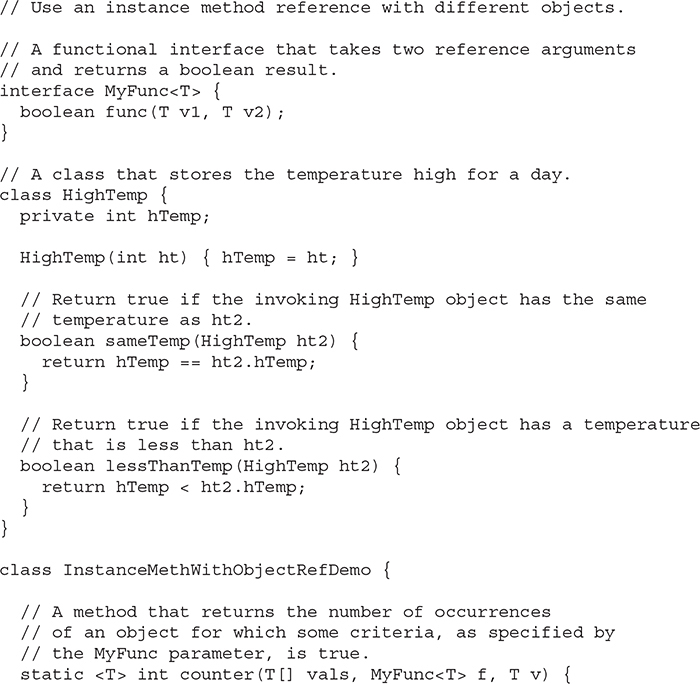

Here, the name of the class is used instead of a specific object, even though an instance method is specified. With this form, the first parameter of the functional interface matches the invoking object and the second parameter matches the parameter specified by the method. Here is an example. It defines a method called counter( ) that counts the number of objects in an array that satisfy the condition defined by the func( ) method of the MyFunc functional interface. In this case, it counts instances of the HighTemp class.

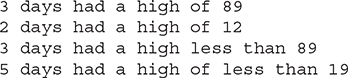

The output is shown here:

In the program, notice that HighTemp has two instance methods: sameTemp( ) and lessThanTemp( ). The first returns true if two HighTemp objects contain the same temperature. The second returns true if the temperature of the invoking object is less than that of the passed object. Each method has a parameter of type HighTemp, and each method returns a boolean result. Thus, each is compatible with the MyFunc functional interface because the invoking object type can be mapped to the first parameter of func( ) and the argument mapped to func( )’s second parameter. Thus, when the expression

HighTemp::sameTemp

is passed to the counter( ) method, an instance of the functional interface MyFunc is created in which the parameter type of the first parameter is that of the invoking object of the instance method, which is HighTemp. The type of the second parameter is also HighTemp because that is the type of the parameter to sameTemp( ). The same is true for the lessThanTemp( ) method.

One other point: you can refer to the superclass version of a method by use of super, as shown here:

super::name

The name of the method is specified by name. Another form is

typeName.super::name

where typeName refers to an enclosing class or super interface.

# Method References with Generics

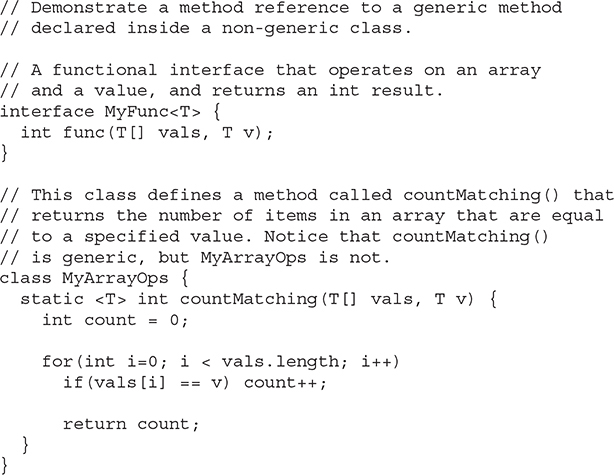

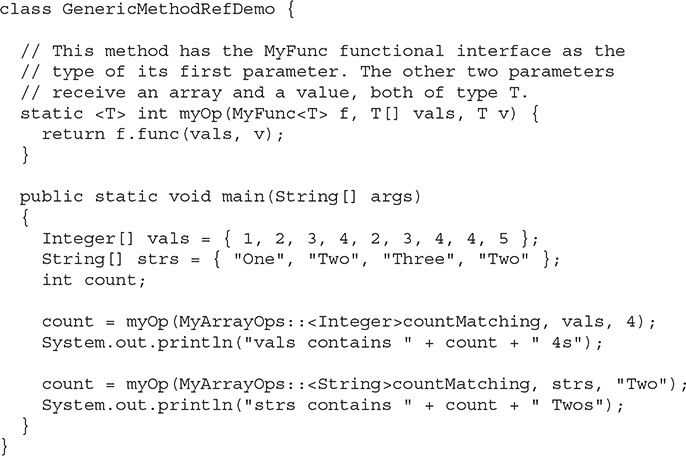

You can use method references with generic classes and/or generic methods. For example, consider the following program:

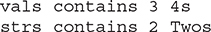

The output is shown here:

In the program, MyArrayOps is a non-generic class that contains a generic method called countMatching( ). The method returns a count of the elements in an array that match a specified value. Notice how the generic type argument is specified. For example, its first call in main( ), shown here:

count = myOp(MyArrayOps::\<Integer\>countMatching, vals, 4);

passes the type argument Integer. Notice that it occurs after the ::. This syntax can be generalized: When a generic method is specified as a method reference, its type argument comes after the :: and before the method name. It is important to point out, however, that explicitly specifying the type argument is not required in this situation (and many others) because the type argument would have been automatically inferred. In cases in which a generic class is specified, the type argument follows the class name and precedes the ::.

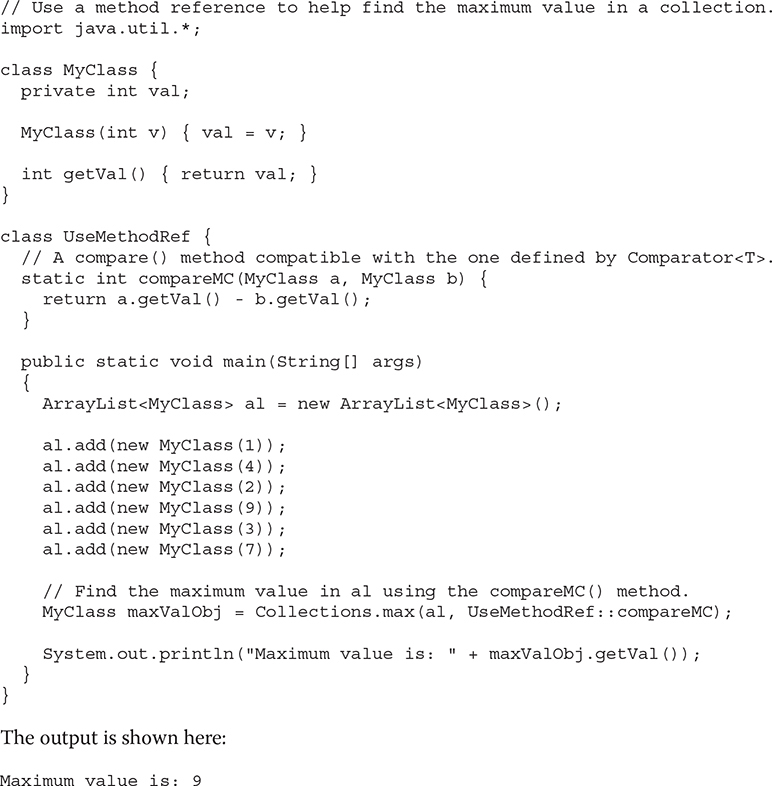

Although the preceding examples show the mechanics of using method references, they don’t show their real benefits. One place method references can be quite useful is in conjunction with the Collections Framework, which is described later in Chapter 20. However, for completeness, a short, but effective, example that uses a method reference to help determine the largest element in a collection is included here. (If you are unfamiliar with the Collections Framework, return to this example after you have worked through Chapter 20.)

One way to find the largest element in a collection is to use the max( ) method defined by the Collections class. For the version of max( ) used here, you must pass a reference to the collection and an instance of an object that implements the Comparator<T> interface. This interface specifies how two objects are compared. It defines only one abstract method, called compare( ), that takes two arguments, each the type of the objects being compared. It must return greater than zero if the first argument is greater than the second, zero if the two arguments are equal, and less than zero if the first object is less than the second.

In the past, to use max( ) with user-defined objects, an instance of Comparator<T> had to be obtained by first explicitly implementing it by a class, and then creating an instance of that class. This instance was then passed as the comparator to max( ). Beginning with JDK 8, it is now possible to simply pass a reference to a comparison method to max( ) because doing so automatically implements the comparator. The following simple example shows the process by creating an ArrayList of MyClass objects and then finding the one in the list that has the highest value (as defined by the comparison method):

The output is shown here:

Maximum value is: 9

In the program, notice that MyClass neither defines any comparison method of its own, nor does it implement Comparator. However, the maximum value of a list of MyClass items can still be obtained by calling max( ) because UseMethodRef defines the static method compareMC( ), which is compatible with the compare( ) method defined by Comparator. Therefore, there is no need to explicitly implement and create an instance of Comparator.

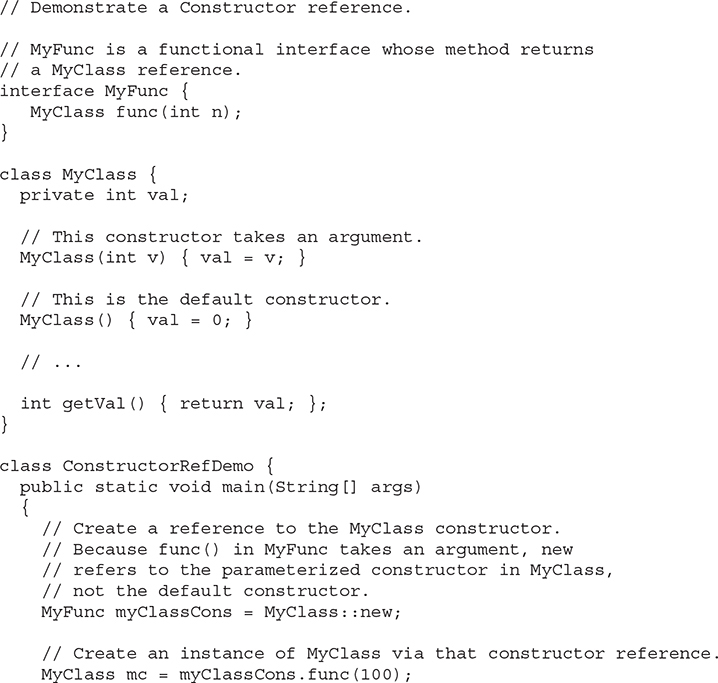

# Constructor References

Similar to the way that you can create references to methods, you can create references to constructors. Here is the general form of the syntax that you will use:

classname::new

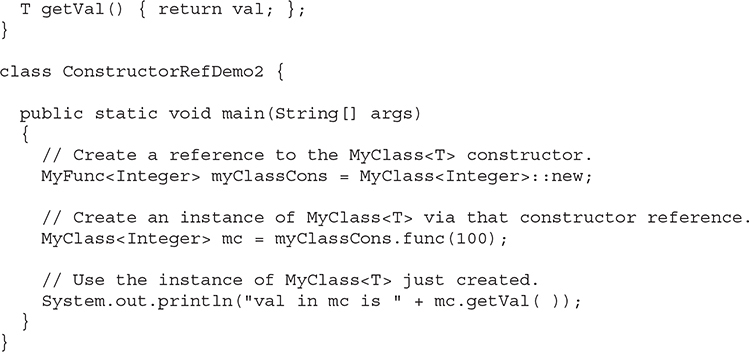

This reference can be assigned to any functional interface reference that defines a method compatible with the constructor. Here is a simple example:

The output is shown here:

val in mc is 100

In the program, notice that the func( ) method of MyFunc returns a reference of type MyClass and has an int parameter. Next, notice that MyClass defines two constructors. The first specifies a parameter of type int. The second is the default, parameterless constructor. Now, examine the following line:

MyFunc myClassCons = MyClass::new;

Here, the expression MyClass::new creates a constructor reference to a MyClass constructor. In this case, because MyFunc’s func( ) method takes an int parameter, the constructor being referred to is MyClass(int v) because it is the one that matches. Also notice that the reference to this constructor is assigned to a MyFunc reference called myClassCons. After this statement executes, myClassCons can be used to create an instance of MyClass, as this line shows:

MyClass mc = myClassCons.func(100);

In essence, myClassCons has become another way to call MyClass(int v).

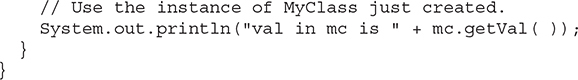

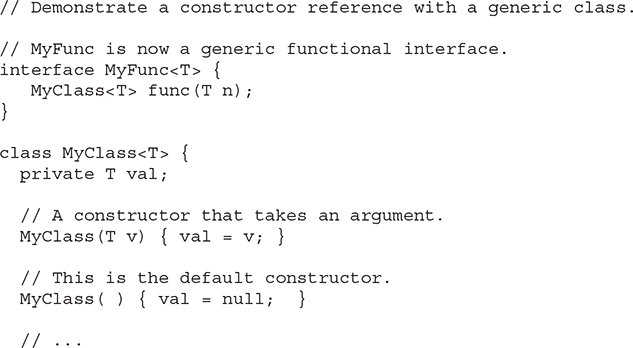

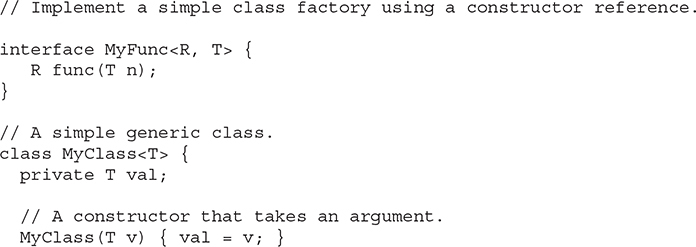

Constructor references to generic classes are created in the same fashion. The only difference is that the type argument can be specified. This works the same as it does for using a generic class to create a method reference: simply specify the type argument after the class name. The following illustrates this by modifying the previous example so that MyFunc and MyClass are generic:

This program produces the same output as the previous version. The difference is that now both MyFunc and MyClass are generic. Thus, the sequence that creates a constructor reference can include a type argument (although one is not always needed), as shown here:

MyFunc\<Integer\> myClassCons = MyClass\<Integer\>::new;

Because the type argument Integer has already been specified when myClassCons is created, it can be used to create a MyClass<Integer> object, as the next line shows:

MyClass\<Integer\> mc = myClassCons.func(100);

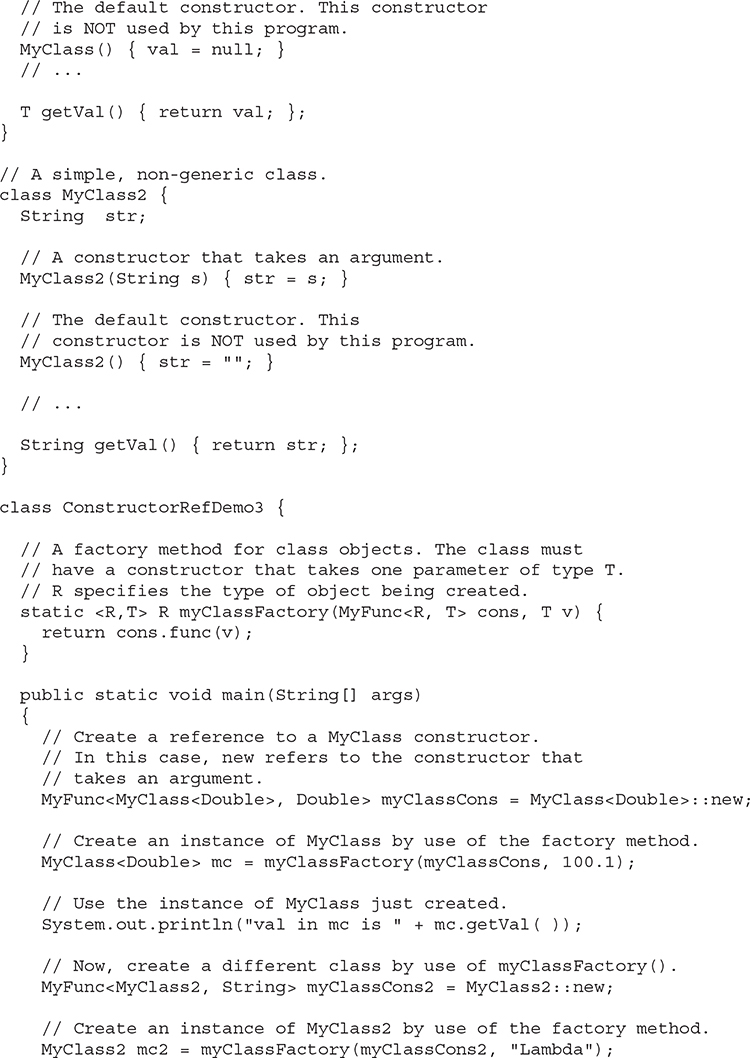

Although the preceding examples demonstrate the mechanics of using a constructor reference, no one would use a constructor reference as just shown because nothing is gained. Furthermore, having what amounts to two names for the same constructor creates a confusing situation (to say the least). However, to give you the flavor of a more practical usage, the following program uses a static method, called myClassFactory( ), that is a factory for objects of any type of MyFunc objects. It can be used to create any type of object that has a constructor compatible with its first parameter.

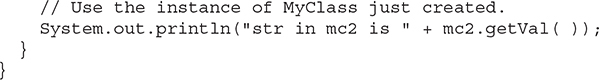

The output is shown here:

As you can see, myClassFactory( ) is used to create objects of type MyClass<Double> and MyClass2. Although both classes differ—for example, MyClass is generic and MyClass2 is not—both can be created by myClassFactory( ) because they both have constructors that are compatible with func( ) in MyFunc. This works because myClassFactory( ) is passed the constructor for the object that it builds. You might want to experiment with this program a bit, trying different classes that you create. Also try creating instances of different types of MyClass objects. As you will see, myClassFactory( ) can create any type of object whose class has a constructor that is compatible with func( ) in MyFunc. Although this example is quite simple, it hints at the power that constructor references bring to Java.

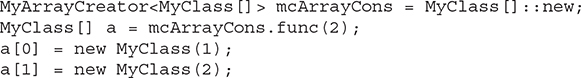

Before moving on, it is important to mention a second form of the constructor reference syntax that is used for arrays. To create a constructor reference for an array, use this construct:

type[]::new

Here, type specifies the type of object being created. For example, assuming the form of MyClass as shown in the first constructor reference example (ConstructorRefDemo) and given the MyArrayCreator interface shown here:

the following creates a two-element array of MyClass objects and gives each element an initial value:

Here, the call to func(2) causes a two-element array to be created. In general, a functional interface must contain a method that takes a single int parameter if it is to be used to refer to an array constructor.

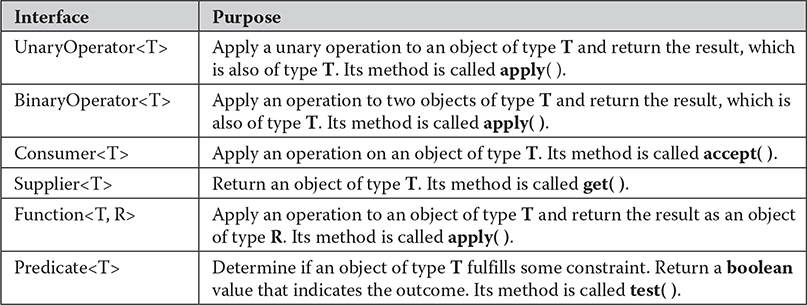

# Predefined Functional Interfaces

Up to this point, the examples in this chapter have defined their own functional interfaces so that the fundamental concepts behind lambda expressions and functional interfaces could be clearly illustrated. However, in many cases, you won’t need to define your own functional interface because the package called java.util.function provides several predefined ones. Although we will look at them more closely in Part II, here is a sampling:

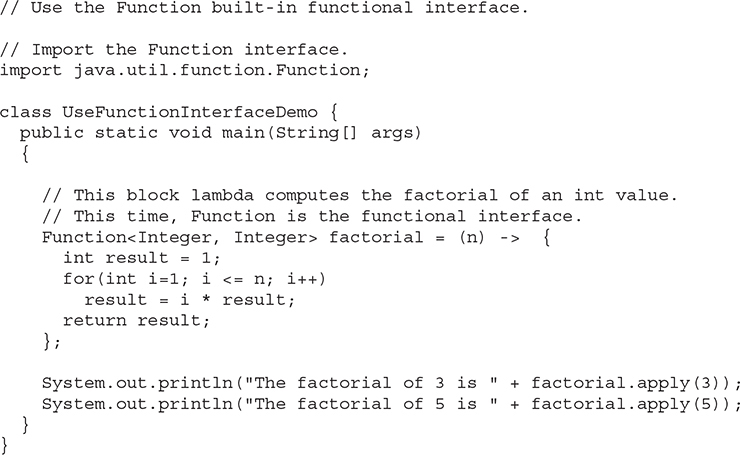

The following program shows the Function interface in action by using it to rework the earlier example called BlockLambdaDemo that demonstrated block lambdas by implementing a factorial example. That example created its own functional interface called NumericFunc, but the built-in Function interface could have been used, as this version of the program illustrates:

It produces the same output as previous versions of the program.