# Methods and Classes

This chapter continues the discussion of methods and classes begun in the preceding chapter. It examines several topics relating to methods, including overloading, parameter passing, and recursion. The chapter then returns to the class, discussing access control, the use of the keyword static, and one of Java’s most important built-in classes: String.

# Overloading Methods

In Java, it is possible to define two or more methods within the same class that share the same name, as long as their parameter declarations are different. When this is the case, the methods are said to be overloaded, and the process is referred to as method overloading. Method overloading is one of the ways that Java supports polymorphism. If you have never used a language that allows the overloading of methods, then the concept may seem strange at first. But as you will see, method overloading is one of Java’s most exciting and useful features.

When an overloaded method is invoked, Java uses the type and/or number of arguments as its guide to determine which version of the overloaded method to actually call. Thus, overloaded methods must differ in the type and/or number of their parameters. While overloaded methods may have different return types, the return type alone is insufficient to distinguish two versions of a method. When Java encounters a call to an overloaded method, it simply executes the version of the method whose parameters match the arguments used in the call.

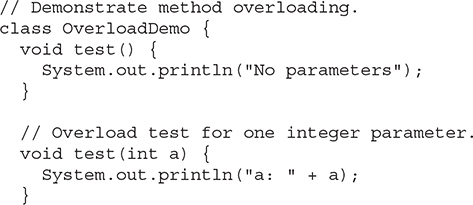

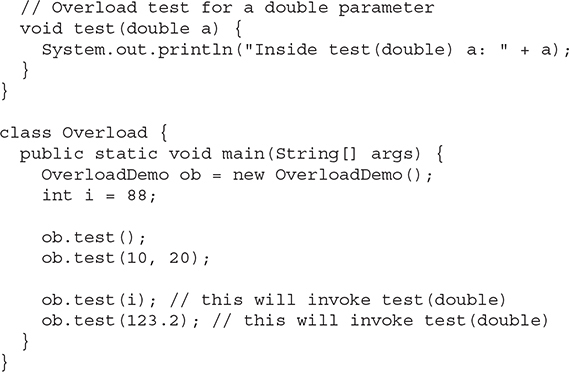

Here is a simple example that illustrates method overloading:

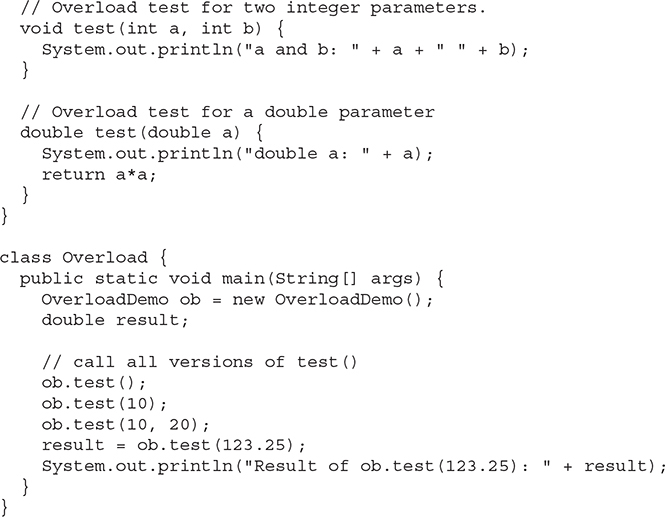

This program generates the following output:

As you can see, test( ) is overloaded four times. The first version takes no parameters, the second takes one integer parameter, the third takes two integer parameters, and the fourth takes one double parameter. The fact that the fourth version of test( ) also returns a value is of no consequence relative to overloading, since return types do not play a role in overload resolution.

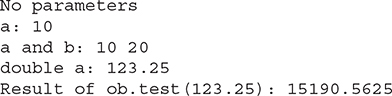

When an overloaded method is called, Java looks for a match between the arguments used to call the method and the method’s parameters. However, this match need not always be exact. In some cases, Java’s automatic type conversions can play a role in overload resolution. For example, consider the following program:

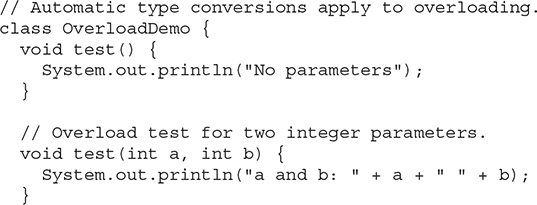

This program generates the following output:

As you can see, this version of OverloadDemo does not define test(int). Therefore, when test( ) is called with an integer argument inside Overload, no matching method is found. However, Java can automatically convert an integer into a double, and this conversion can be used to resolve the call. Therefore, after test(int) is not found, Java elevates i to double and then calls test(double). Of course, if test(int) had been defined, it would have been called instead. Java will employ its automatic type conversions only if no exact match is found.

Method overloading supports polymorphism because it is one way that Java implements the “one interface, multiple methods” paradigm. To understand how, consider the following. In languages that do not support method overloading, each method must be given a unique name. However, frequently you will want to implement essentially the same method for different types of data. Consider the absolute value function. In languages that do not support overloading, there are usually three or more versions of this function, each with a slightly different name. For instance, in C, the function abs( ) returns the absolute value of an integer, labs( ) returns the absolute value of a long integer, and fabs( ) returns the absolute value of a floating-point value. Since C does not support overloading, each function has its own name, even though all three functions do essentially the same thing. This makes the situation more complex, conceptually, than it actually is. Although the underlying concept of each function is the same, you still have three names to remember. This situation does not occur in Java, because each absolute value method can use the same name. Indeed, Java’s standard class library includes an absolute value method, called abs( ). This method is overloaded by Java’s Math class to handle all numeric types. Java determines which version of abs( ) to call based upon the type of argument.

The value of overloading is that it allows related methods to be accessed by use of a common name. Thus, the name abs represents the general action that is being performed. It is left to the compiler to choose the right specific version for a particular circumstance. You, the programmer, need only remember the general operation being performed. Through the application of polymorphism, several names have been reduced to one. Although this example is fairly simple, if you expand the concept, you can see how overloading can help you manage greater complexity.

When you overload a method, each version of that method can perform any activity you desire. There is no rule stating that overloaded methods must relate to one another. However, from a stylistic point of view, method overloading implies a relationship. Thus, while you can use the same name to overload unrelated methods, you should not. For example, you could use the name sqr to create methods that return the square of an integer and the square root of a floating-point value. But these two operations are fundamentally different. Applying method overloading in this manner defeats its original purpose. In practice, you should only overload closely related operations.

# Overloading Constructors

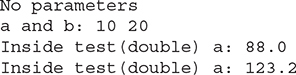

In addition to overloading normal methods, you can also overload constructor methods. In fact, for most real-world classes that you create, overloaded constructors will be the norm, not the exception. To understand why, let’s return to the Box class developed in the preceding chapter. Following is the latest version of Box:

As you can see, the Box( ) constructor requires three parameters. This means that all declarations of Box objects must pass three arguments to the Box( ) constructor. For example, the following statement is currently invalid:

Box ob = new Box();

Since Box( ) requires three arguments, it’s an error to call it without them. This raises some important questions. What if you simply wanted a box and did not care (or know) what its initial dimensions were? Or, what if you want to be able to initialize a cube by specifying only one value that would be used for all three dimensions? As the Box class is currently written, these other options are not available to you.

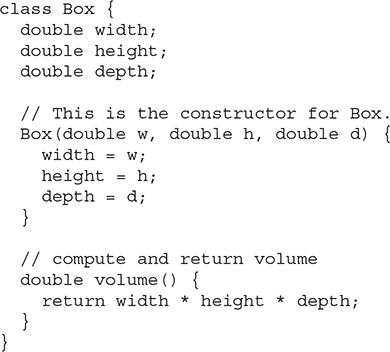

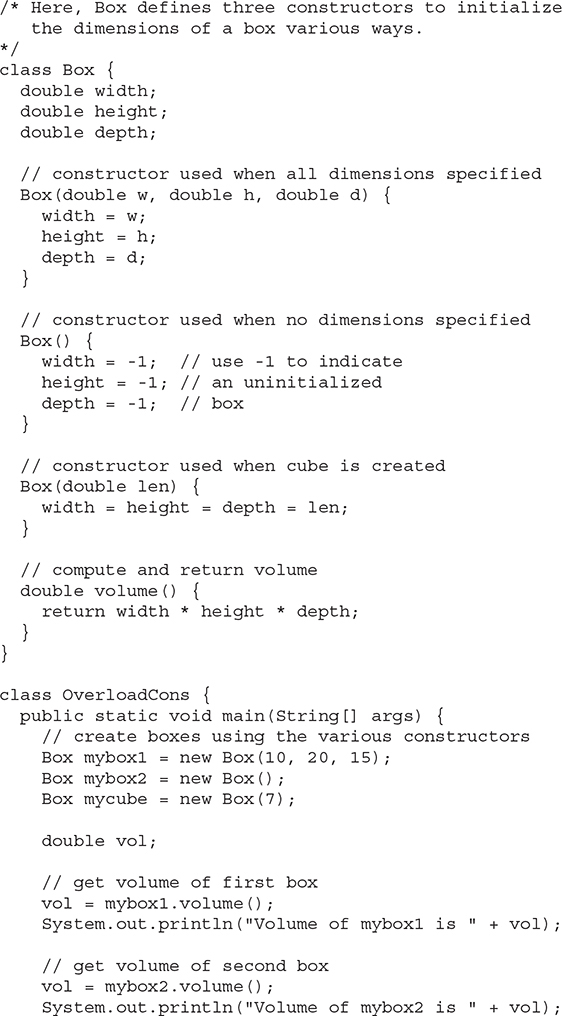

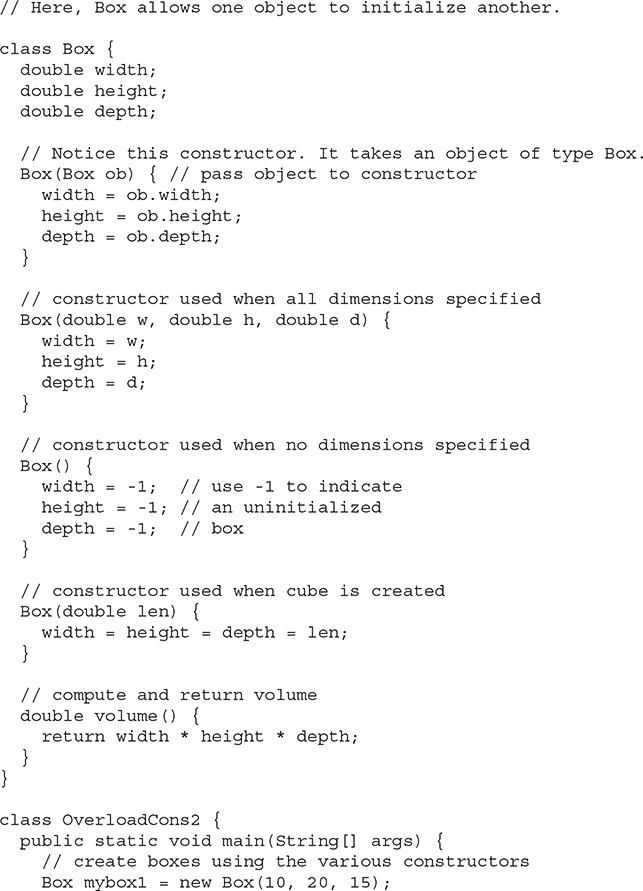

Fortunately, the solution to these problems is quite easy: simply overload the Box constructor so that it handles the situations just described. Here is a program that contains an improved version of Box that does just that:

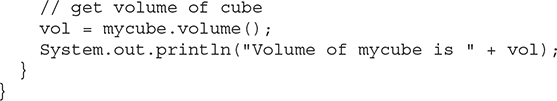

The output produced by this program is shown here:

As you can see, the proper overloaded constructor is called based upon the arguments specified when new is executed.

# Using Objects as Parameters

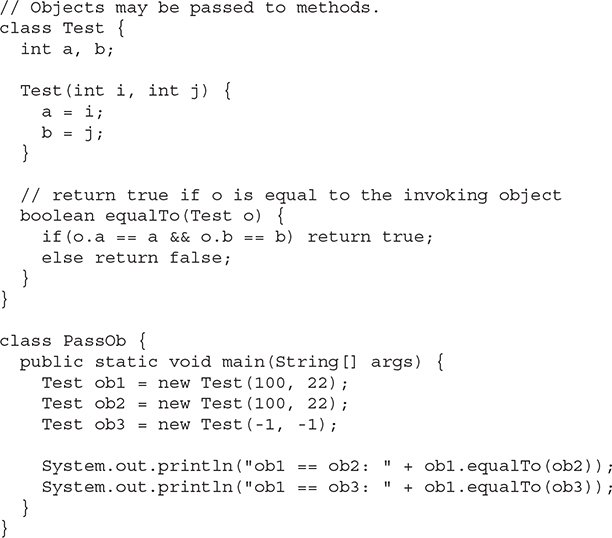

So far, we have only been using simple types as parameters to methods. However, it is both correct and common to pass objects to methods. For example, consider the following short program:

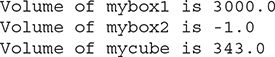

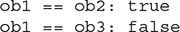

This program generates the following output:

As you can see, the equalTo( ) method inside Test compares two objects for equality and returns the result. That is, it compares the invoking object with the one that it is passed. If they contain the same values, then the method returns true. Otherwise, it returns false. Notice that the parameter o in equalTo( ) specifies Test as its type. Although Test is a class type created by the program, it is used in just the same way as Java’s built-in types.

One of the most common uses of object parameters involves constructors. Frequently, you will want to construct a new object so that it is initially the same as some existing object. To do this, you must define a constructor that takes an object of its class as a parameter. For example, the following version of Box allows one object to initialize another:

As you will see when you begin to create your own classes, providing many forms of constructors is usually required to allow objects to be constructed in a convenient and efficient manner.

# A Closer Look at Argument Passing

In general, there are two ways that a computer language can pass an argument to a subroutine. The first way is call-by-value. This approach copies the value of an argument into the formal parameter of the subroutine. Therefore, changes made to the parameter of the subroutine have no effect on the argument. The second way an argument can be passed is call-by-reference. In this approach, a reference to an argument (not the value of the argument) is passed to the parameter. Inside the subroutine, this reference is used to access the actual argument specified in the call. This means that changes made to the parameter will affect the argument used to call the subroutine. As you will see, although Java uses call-by-value to pass all arguments, the precise effect differs between whether a primitive type or a reference type is passed.

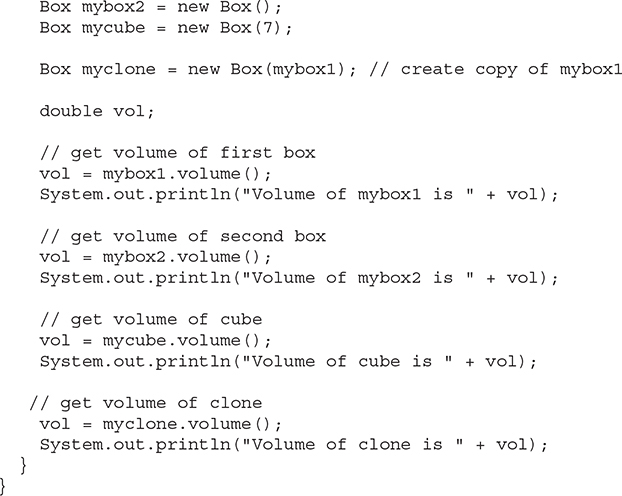

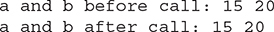

When you pass a primitive type to a method, it is passed by value. Thus, a copy of the argument is made, and what occurs to the parameter that receives the argument has no effect outside the method. For example, consider the following program:

The output from this program is shown here:

As you can see, the operations that occur inside meth( ) have no effect on the values of a and b used in the call; their values here did not change to 30 and 10.

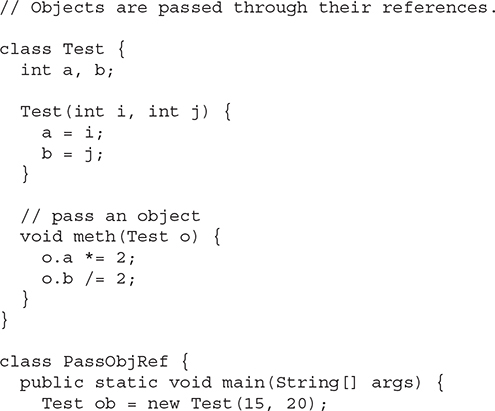

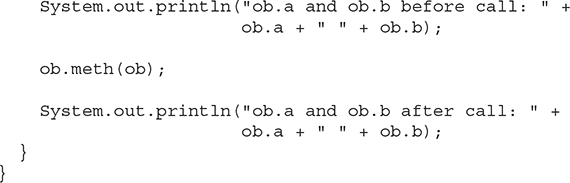

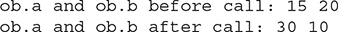

When you pass an object to a method, the situation changes dramatically, because objects are passed by what is effectively call-by-reference. Keep in mind that when you create a variable of a class type, you are only creating a reference to an object. Thus, when you pass this reference to a method, the parameter that receives it will refer to the same object as that referred to by the argument. This effectively means that objects act as if they are passed to methods by use of call-by-reference. Changes to the object inside the method do affect the object used as an argument. For example, consider the following program:

This program generates the following output:

As you can see, in this case, the actions inside meth( ) have affected the object used as an argument.

REMEMBER When an object reference is passed to a method, the reference itself is passed by use of call-by-value. However, since the value being passed refers to an object, the copy of that value will still refer to the same object that its corresponding argument does.

# Returning Objects

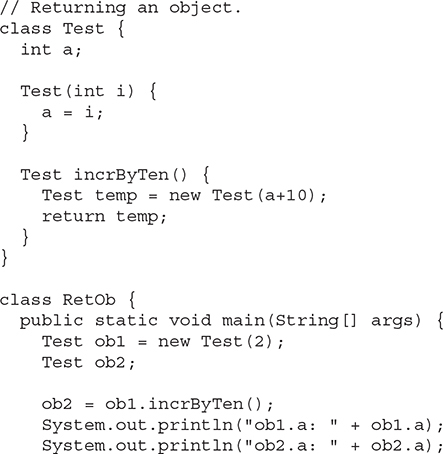

A method can return any type of data, including class types that you create. For example, in the following program, the incrByTen( ) method returns an object in which the value of a is ten greater than it is in the invoking object.

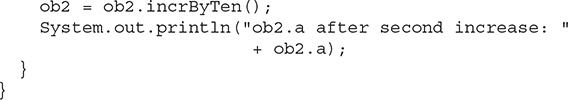

The output generated by this program is shown here:

As you can see, each time incrByTen( ) is invoked, a new object is created, and a reference to it is returned to the calling routine.

The preceding program makes another important point: Since all objects are dynamically allocated using new, you don’t need to worry about an object going out of scope because the method in which it was created terminates. The object will continue to exist as long as there is a reference to it somewhere in your program. When there are no references to it, the object will be reclaimed the next time garbage collection takes place.

# Recursion

Java supports recursion. Recursion is the process of defining something in terms of itself. As it relates to Java programming, recursion is the attribute that allows a method to call itself. A method that calls itself is said to be recursive.

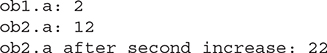

The classic example of recursion is the computation of the factorial of a number. The factorial of a number N is the product of all the whole numbers between 1 and N. For example, 3 factorial is 1 × 2 × 3, or 6. Here is how a factorial can be computed by use of a recursive method:

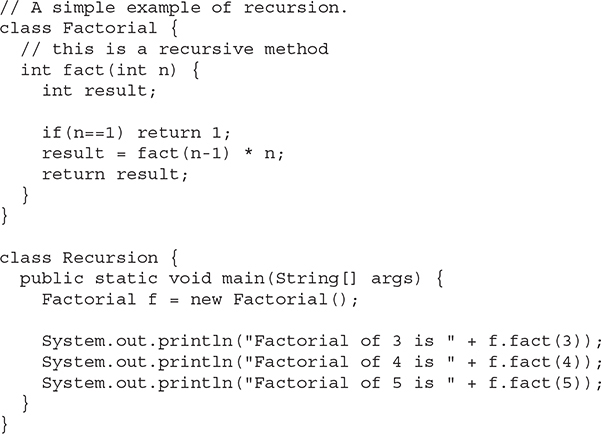

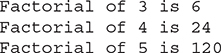

The output from this program is shown here:

If you are unfamiliar with recursive methods, then the operation of fact( ) may seem a bit confusing. Here is how it works. When fact( ) is called with an argument of 1, the function returns 1; otherwise, it returns the product of fact(n–1)*n. To evaluate this expression, fact( ) is called with n–1. This process repeats until n equals 1 and the calls to the method begin returning.

To better understand how the fact( ) method works, let’s go through a short example. When you compute the factorial of 3, the first call to fact( ) will cause a second call to be made with an argument of 2. This invocation will cause fact( ) to be called a third time with an argument of 1. This call will return 1, which is then multiplied by 2 (the value of n in the second invocation). This result (which is 2) is then returned to the original invocation of fact( ) and multiplied by 3 (the original value of n). This yields the answer, 6. You might find it interesting to insert println( ) statements into fact( ), which will show at what level each call is and what the intermediate answers are.

When a method calls itself, new local variables and parameters are allocated storage on the stack, and the method code is executed with these new variables from the start. As each recursive call returns, the old local variables and parameters are removed from the stack, and execution resumes at the point of the call inside the method. Recursive methods could be said to “telescope” out and back.

Recursive versions of many routines may execute a bit more slowly than the iterative equivalent because of the added overhead of the additional method calls. A large number of recursive calls to a method could cause a stack overrun. Because storage for parameters and local variables is on the stack and each new call creates a new copy of these variables, it is possible that the stack could be exhausted. If this occurs, the Java run-time system will cause an exception. However, this is typically not an issue unless a recursive routine runs wild.

The main advantage to recursive methods is that they can be used to create clearer and simpler versions of several algorithms than can their iterative relatives. For example, the QuickSort sorting algorithm is quite difficult to implement in an iterative way. Also, some types of AI-related algorithms are most easily implemented using recursive solutions.

When writing recursive methods, you must have an if statement somewhere to force the method to return without the recursive call being executed. If you don’t do this, once you call the method, it will never return. This is a very common error in working with recursion. Use println( ) statements liberally during development so that you can watch what is going on and abort execution if you see that you have made a mistake.

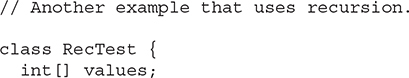

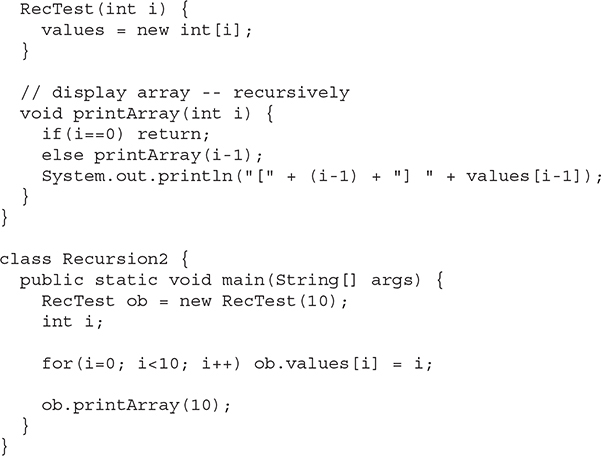

Here is one more example of recursion. The recursive method printArray( ) prints the first i elements in the array values.

This program generates the following output:

# Introducing Access Control

As you know, encapsulation links data with the code that manipulates it. However, encapsulation provides another important attribute: access control. Through encapsulation, you can control what parts of a program can access the members of a class. By controlling access, you can prevent misuse. For example, allowing access to data only through a well-defined set of methods, you can prevent the misuse of that data. Thus, when correctly implemented, a class creates a “black box” that may be used, but the inner workings of which are not open to tampering. However, the classes that were presented earlier do not completely meet this goal. For example, consider the Stack class shown at the end of Chapter 6. While it is true that the methods push( ) and pop( ) do provide a controlled interface to the stack, this interface is not enforced. That is, it is possible for another part of the program to bypass these methods and access the stack directly. Of course, in the wrong hands, this could lead to trouble. In this section, you will be introduced to the mechanism by which you can precisely control access to the various members of a class.

How a member can be accessed is determined by the access modifier attached to its declaration. Java supplies a rich set of access modifiers. Some aspects of access control are related mostly to inheritance or packages. (A package is, essentially, a grouping of classes.) These parts of Java’s access control mechanism will be discussed in subsequent chapters. Here, let’s begin by examining access control as it applies to a single class. Once you understand the fundamentals of access control, the rest will be easy.

NOTE The modules feature added by JDK 9 can also impact accessibility. Modules are described in Chapter 16.

Java’s access modifiers are public, private, and protected. Java also defines a default access level. protected applies only when inheritance is involved. The other access modifiers are described next.

Let’s begin by defining public and private. When a member of a class is modified by public, then that member can be accessed by any other code. When a member of a class is specified as private, then that member can only be accessed by other members of its class. Now you can understand why main( ) has always been preceded by the public modifier. It is called by code that is outside the program—that is, by the Java run-time system. When no access modifier is used, then by default the member of a class is public within its own package, but cannot be accessed outside of its package. (Packages are discussed in Chapter 9.)

In the classes developed so far, all members of a class have used the default access mode. However, this is not what you will typically want to be the case. Usually, you will want to restrict access to the data members of a class—allowing access only through methods. Also, there will be times when you will want to define methods that are private to a class.

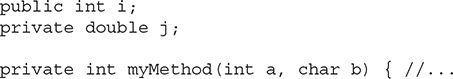

An access modifier precedes the rest of a member’s type specification. That is, it must begin a member’s declaration statement. Here is an example:

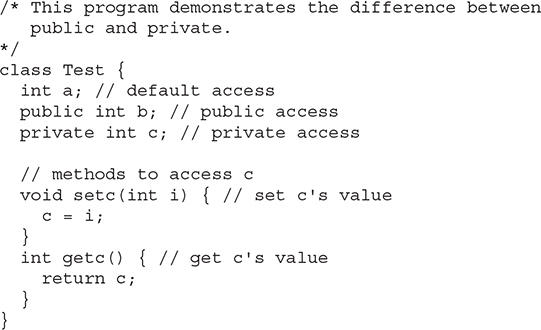

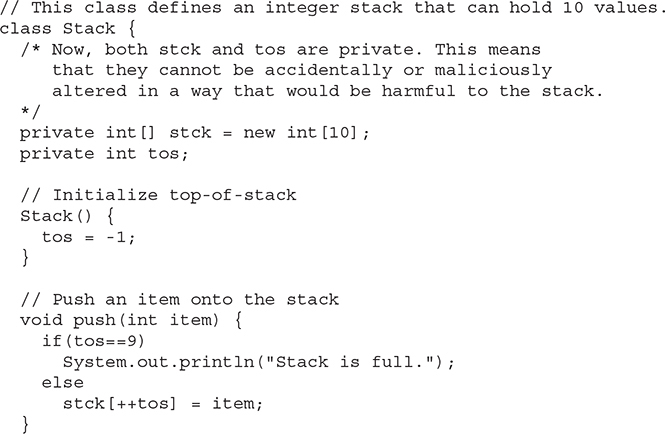

To understand the effects of public and private access, consider the following program:

As you can see, inside the Test class, a uses default access, which for this example is the same as specifying public. b is explicitly specified as public. Member c is given private access. This means that it cannot be accessed by code outside of its class. So, inside the AccessTest class, c cannot be used directly. It must be accessed through its public methods: setc( ) and getc( ). If you were to remove the comment symbol from the beginning of the following line,

// ob.c = 100; // Error!

then you would not be able to compile this program because of the access violation.

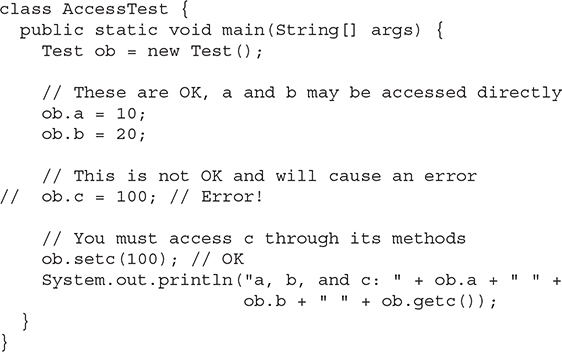

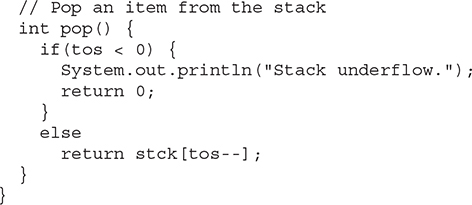

To see how access control can be applied to a more practical example, consider the following improved version of the Stack class shown at the end of Chapter 6:

As you can see, now both stck, which holds the stack, and tos, which is the index of the top of the stack, are specified as private. This means that they cannot be accessed or altered except through push( ) and pop( ). Making tos private, for example, prevents other parts of your program from inadvertently setting it to a value that is beyond the end of the stck array.

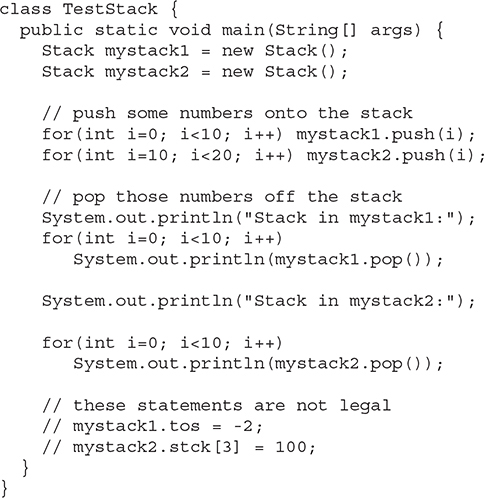

The following program demonstrates the improved Stack class. Try removing the commented-out lines to prove to yourself that the stck and tos members are, indeed, inaccessible.

Although methods will usually provide access to the data defined by a class, this does not always have to be the case. It is perfectly proper to allow an instance variable to be public when there is good reason to do so. For example, most of the simple classes in this book were created with little concern about controlling access to instance variables for the sake of simplicity. However, in most real-world classes, you will need to allow operations on data only through methods. The next chapter will return to the topic of access control. As you will see, it is particularly important when inheritance is involved.

# Understanding static

There will be times when you will want to define a class member that will be used independently of any object of that class. Normally, a class member must be accessed only in conjunction with an object of its class. However, it is possible to create a member that can be used by itself, without reference to a specific instance. To create such a member, precede its declaration with the keyword static. When a member is declared static, it can be accessed before any objects of its class are created, and without reference to any object. You can declare both methods and variables to be static. The most common example of a static member is main( ). main( ) is declared as static because it must be called before any objects exist.

Instance variables declared as static are, essentially, global variables. When objects of its class are declared, no copy of a static variable is made. Instead, all instances of the class share the same static variable.

Methods declared as static have several restrictions:

• They can only directly call other static methods of their class.

• They can only directly access static variables of their class.

• They cannot refer to this or super in any way. (The keyword super relates to inheritance and is described in the next chapter.)

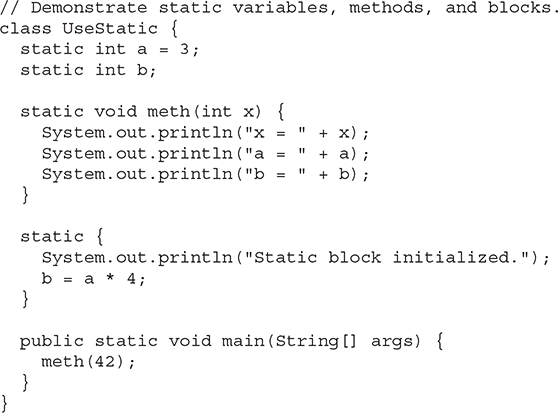

If you need to do computation in order to initialize your static variables, you can declare a static block that gets executed exactly once, when the class is first loaded. The following example shows a class that has a static method, some static variables, and a static initialization block:

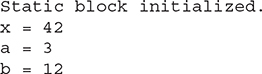

As soon as the UseStatic class is loaded, all of the static statements are run. First, a is set to 3, then the static block executes, which prints a message and then initializes b to a*4 or 12. Then main( ) is called, which calls meth( ), passing 42 to x. The three println( ) statements refer to the two static variables a and b, as well as to the parameter x.

Here is the output of the program:

Outside of the class in which they are defined, static methods and variables can be used independently of any object. To do so, you need only specify the name of their class followed by the dot operator. For example, if you wish to call a static method from outside its class, you can do so using the following general form:

classname.method( )

Here, classname is the name of the class in which the static method is declared. As you can see, this format is similar to that used to call non-static methods through object-reference variables. A static variable can be accessed in the same way—by use of the dot operator on the name of the class. This is how Java implements a controlled version of global methods and global variables.

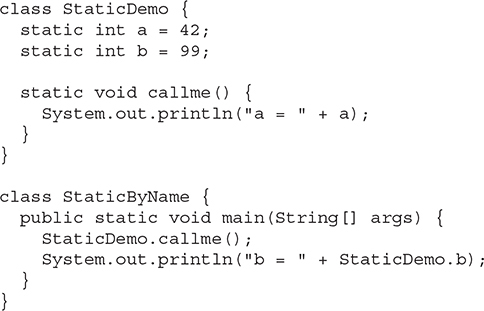

Here is an example. Inside main( ), the static method callme( ) and the static variable b are accessed through their class name StaticDemo.

Here is the output of this program:

# Introducing final

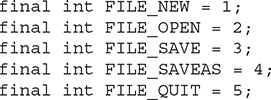

A field can be declared as final. Doing so prevents its contents from being modified, making it, essentially, a constant. This means that you must initialize a final field when it is declared. You can do this in one of two ways: First, you can give it a value when it is declared. Second, you can assign it a value within a constructor. The first approach is probably the most common. Here is an example:

Subsequent parts of your program can now use FILE_OPEN, etc., as if they were constants, without fear that a value has been changed. It is a common coding convention to choose all uppercase identifiers for final fields, as this example shows.

In addition to fields, both method parameters and local variables can be declared final. Declaring a parameter final prevents it from being changed within the method. Declaring a local variable final prevents it from being assigned a value more than once.

The keyword final can also be applied to methods, but its meaning is substantially different than when it is applied to variables. This additional usage of final is explained in the next chapter, when inheritance is described.

# Arrays Revisited

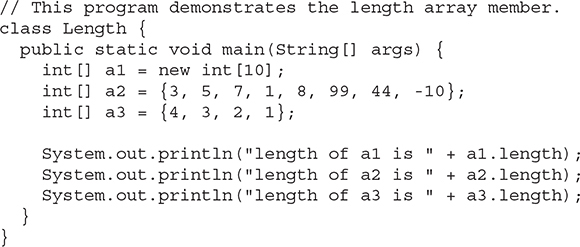

Arrays were introduced earlier in this book, before classes had been discussed. Now that you know about classes, an important point can be made about arrays: they are implemented as objects. Because of this, there is a special array attribute that you will want to take advantage of. Specifically, the size of an array—that is, the number of elements that an array can hold—is found in its length instance variable. All arrays have this variable, and it will always hold the size of the array. Here is a program that demonstrates this property:

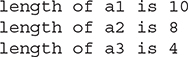

This program displays the following output:

As you can see, the size of each array is displayed. Keep in mind that the value of length has nothing to do with the number of elements that are actually in use. It only reflects the number of elements that the array is designed to hold.

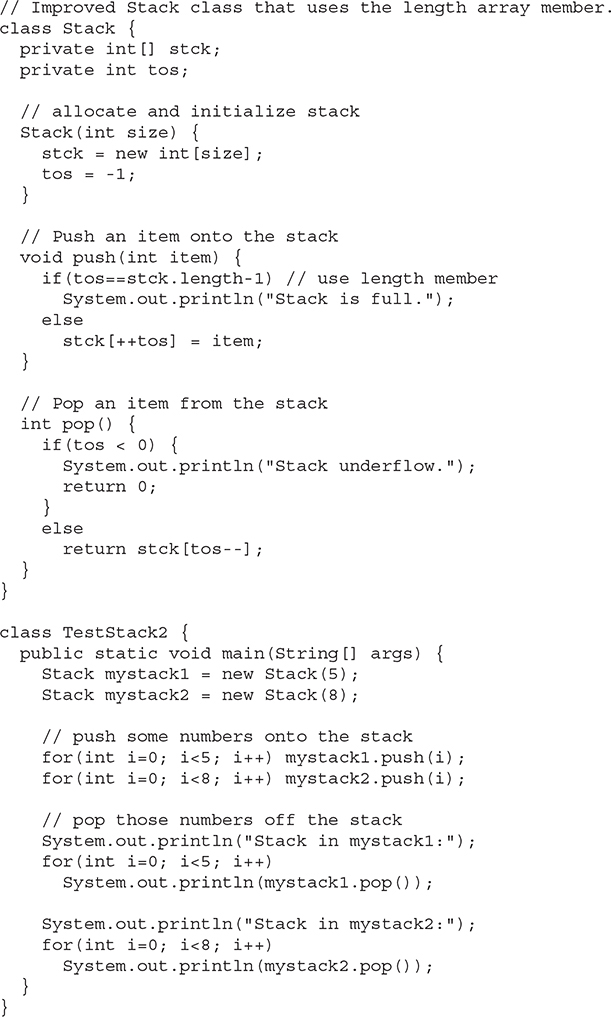

You can put the length member to good use in many situations. For example, here is an improved version of the Stack class. As you might recall, the earlier versions of this class always created a ten-element stack. The following version lets you create stacks of any size. The value of stck.length is used to prevent the stack from overflowing.

Notice that the program creates two stacks: one five elements deep and the other eight elements deep. As you can see, the fact that arrays maintain their own length information makes it easy to create stacks of any size.

# Introducing Nested and Inner Classes

It is possible to define a class within another class; such classes are known as nested classes. The scope of a nested class is bounded by the scope of its enclosing class. Thus, if class B is defined within class A, then B does not exist independently of A. A nested class has access to the members, including private members, of the class in which it is nested. However, the enclosing class does not have access to the members of the nested class. A nested class that is declared directly within its enclosing class scope is a member of its enclosing class. It is also possible to declare a nested class that is local to a block.

There are two types of nested classes: static and inner. A static nested class is one that has the static modifier applied. Because it is static, it must access the non-static members of its enclosing class through an object. That is, it cannot refer to non-static members of its enclosing class directly.

The second type of nested class is the inner class. An inner class is a non-static nested class. It has access to all of the variables and methods of its outer class and may refer to them directly in the same way that other non-static members of the outer class do.

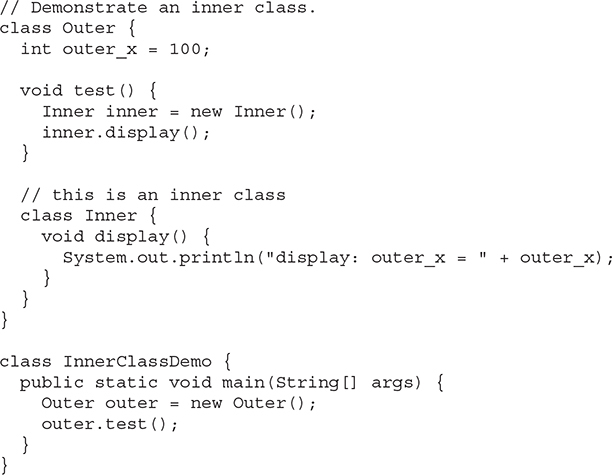

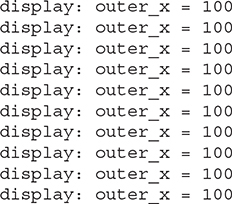

The following program illustrates how to define and use an inner class. The class named Outer has one instance variable named outer_x, one instance method named test( ), and defines one inner class called Inner.

Output from this application is shown here:

display: outer_x = 100

In the program, an inner class named Inner is defined within the scope of class Outer. Therefore, any code in class Inner can directly access the variable outer_x. An instance method named display( ) is defined inside Inner. This method displays outer_x on the standard output stream. The main( ) method of InnerClassDemo creates an instance of class Outer and invokes its test( ) method. That method creates an instance of class Inner, and the display( ) method is called.

It is important to realize that an instance of Inner can be created only in the context of class Outer. The Java compiler generates an error message otherwise. In general, an inner class instance is often created by code within its enclosing scope, as the example does.

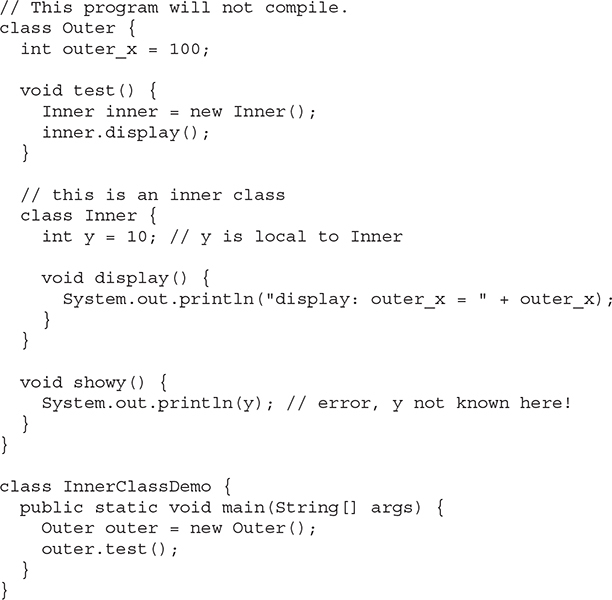

As explained, an inner class has access to all of the members of its enclosing class, but the reverse is not true. Members of the inner class are known only within the scope of the inner class and may not be used by the outer class. For example:

Here, y is declared as an instance variable of Inner. Thus, it is not known outside of that class and it cannot be used by showy( ).

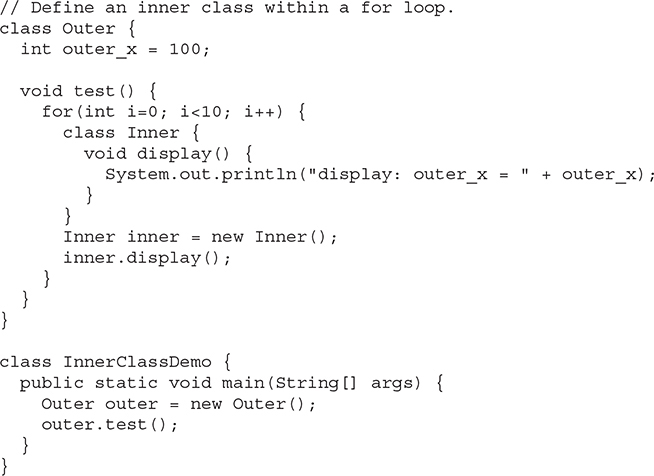

Although we have been focusing on inner classes declared as members within an outer class scope, it is possible to define inner classes within any block scope. For example, you can define a nested class within the block defined by a method or even within the body of a for loop, as this next program shows:

The output from this version of the program is shown here:

While nested classes are not applicable to all situations, they are particularly helpful when handling events. We will return to the topic of nested classes in Chapter 25. There you will see how inner classes can be used to simplify the code needed to handle certain types of events. You will also learn about anonymous inner classes, which are inner classes that don’t have a name.

One point of interest: Nested classes were not allowed by the original 1.0 specification for Java. They were added by Java 1.1.

# Exploring the String Class

Although the String class will be examined in depth in Part II of this book, a short exploration of it is warranted now, because we will be using strings in some of the sample programs shown toward the end of Part I. String is probably the most commonly used class in Java’s class library. The obvious reason for this is that strings are a very important part of programming.

The first thing to understand about strings is that every string you create is actually an object of type String. Even string constants are actually String objects. For example, in the statement

System.out.println("This is a String, too");

the string "This is a String, too" is a String object.

The second thing to understand about strings is that objects of type String are immutable; once a String object is created, its contents cannot be altered. While this may seem like a serious restriction, it is not, for two reasons:

• If you need to change a string, you can always create a new one that contains the modifications.

• Java defines peer classes of String, called StringBuffer and StringBuilder, that allow strings to be altered, so all of the normal string manipulations are still available in Java. (StringBuffer and StringBuilder are described in Part II of this book.)

Strings can be constructed in a variety of ways. The easiest is to use a statement like this:

String myString = "this is a test";

Once you have created a String object, you can use it anywhere that a string is allowed. For example, this statement displays myString:

System.out.println(myString);

Java defines one operator for String objects: +. It is used to concatenate two strings. For example, the statement

String myString = "I" + " like " + "Java.";

results in myString containing "I like Java."

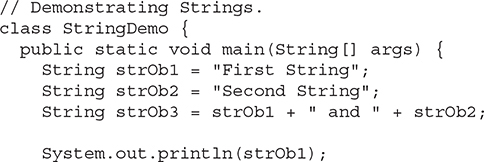

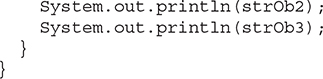

The following program demonstrates the preceding concepts:

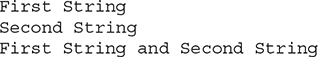

The output produced by this program is shown here:

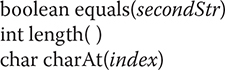

The String class contains several methods that you can use. Here are a few. You can test two strings for equality by using equals( ). You can obtain the length of a string by calling the length( ) method. You can obtain the character at a specified index within a string by calling charAt( ). The general forms of these three methods are shown here:

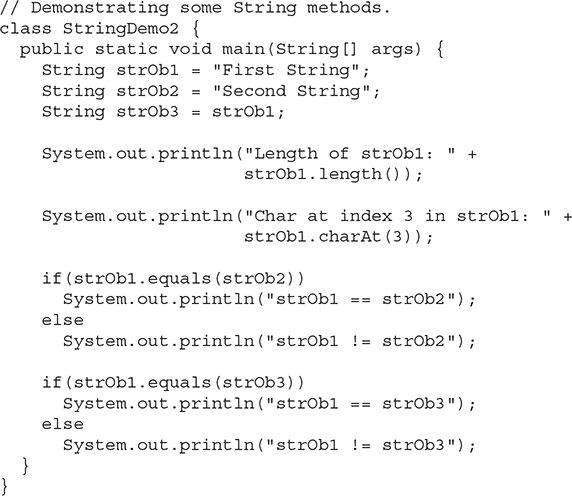

Here is a program that demonstrates these methods:

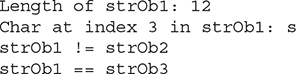

This program generates the following output:

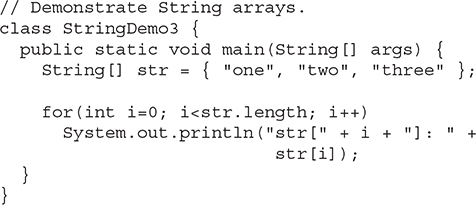

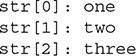

Of course, you can have arrays of strings, just like you can have arrays of any other type of object. For example:

Here is the output from this program:

As you will see in the following section, string arrays play an important part in many Java programs.

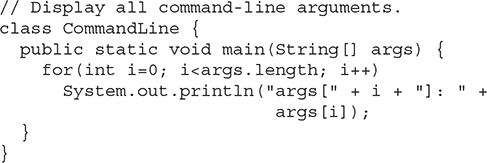

# Using Command-Line Arguments

Sometimes you will want to pass information into a program when you run it. This is accomplished by passing command-line arguments to main( ). A command-line argument is the information that directly follows the program’s name on the command line when it is executed. To access the command-line arguments inside a Java program is quite easy—they are stored as strings in a String array passed to the args parameter of main( ). The first command-line argument is stored at args[0], the second at args[1], and so on. For example, the following program displays all of the command-line arguments that it is called with:

Try executing this program, as shown here:

java CommandLine this is a test 100 -1

When you do, you will see the following output:

REMEMBER All command-line arguments are passed as strings. You must convert numeric values to their internal forms manually, as explained in Chapter 19.

# Varargs: Variable-Length Arguments

Modern versions of Java include a feature that simplifies the creation of methods that need to take a variable number of arguments. This feature is called varargs, and it is short for variable-length arguments. A method that takes a variable number of arguments is called a variable-arity method, or simply a varargs method.

Situations that require that a variable number of arguments be passed to a method are not unusual. For example, a method that opens an Internet connection might take a user name, password, filename, protocol, and so on, but supply defaults if some of this information is not provided. In this situation, it would be convenient to pass only the arguments to which the defaults did not apply. Another example is the printf( ) method that is part of Java’s I/O library. As you will see in Chapter 22, it takes a variable number of arguments, which it formats and then outputs.

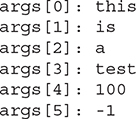

In the early days of Java, variable-length arguments could be handled two ways, neither of which was particularly pleasing. First, if the maximum number of arguments was small and known, then you could create overloaded versions of the method, one for each way the method could be called. Although this works and is suitable for some cases, it applies to only a narrow class of situations.

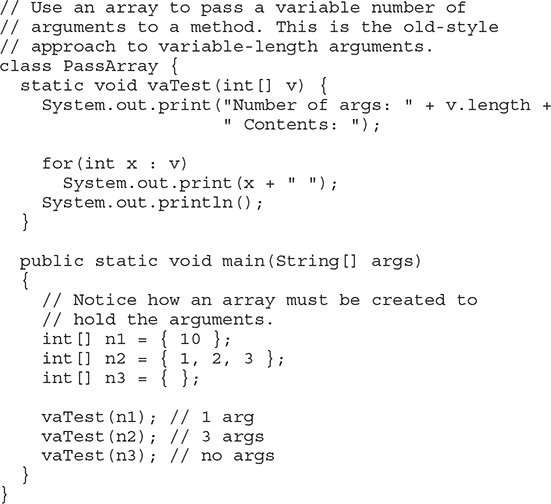

In cases where the maximum number of potential arguments was larger, or unknowable, a second approach was used in which the arguments were put into an array, and then the array was passed to the method. This approach, which you may still find in older legacy code, is illustrated by the following program:

The output from the program is shown here:

In the program, the method vaTest( ) is passed its arguments through the array v. This old-style approach to variable-length arguments does enable vaTest( ) to take an arbitrary number of arguments. However, it requires that these arguments be manually packaged into an array prior to calling vaTest( ). Not only is it tedious to construct an array each time vaTest( ) is called, it is potentially error-prone. The varargs feature offers a simpler, better option.

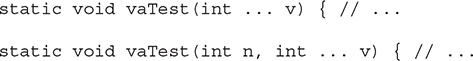

A variable-length argument is specified by three periods (…). For example, here is how vaTest( ) is written using a vararg:

static void vaTest(int ... v) {

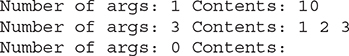

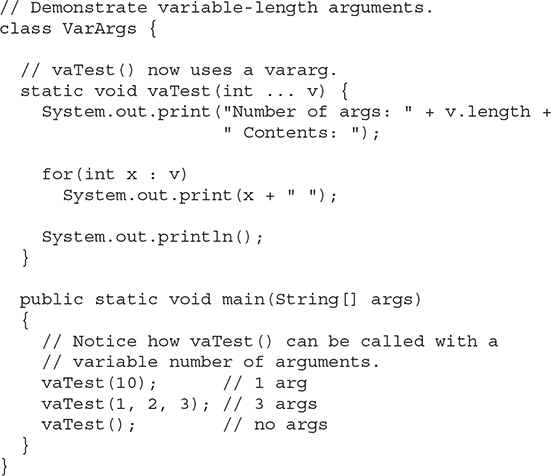

This syntax tells the compiler that vaTest( ) can be called with zero or more arguments. As a result, v is implicitly declared as an array of type int[ ]. Thus, inside vaTest( ), v is accessed using the normal array syntax. Here is the preceding program rewritten using a vararg:

The output from the program is the same as the original version.

There are two important things to notice about this program. First, as explained, inside vaTest( ), v is operated on as an array. This is because v is an array. The … syntax simply tells the compiler that a variable number of arguments will be used and that these arguments will be stored in the array referred to by v. Second, in main( ), vaTest( ) is called with different numbers of arguments, including no arguments at all. The arguments are automatically put in an array and passed to v. In the case of no arguments, the length of the array is zero.

A method can have “normal” parameters along with a variable-length parameter. However, the variable-length parameter must be the last parameter declared by the method. For example, this method declaration is perfectly acceptable:

int doIt(int a, int b, double c, int ... vals) {

In this case, the first three arguments used in a call to doIt( ) are matched to the first three parameters. Then, any remaining arguments are assumed to belong to vals.

Remember, the varargs parameter must be last. For example, the following declaration is incorrect:

int doIt(int a, int b, double c, int ... vals, boolean stopFlag) { // Error!

Here, there is an attempt to declare a regular parameter after the varargs parameter, which is illegal.

There is one more restriction to be aware of: there must be only one varargs parameter. For example, this declaration is also invalid:

int doIt(int a, int b, double c, int ... vals, double ... morevals) { // Error!

The attempt to declare the second varargs parameter is illegal.

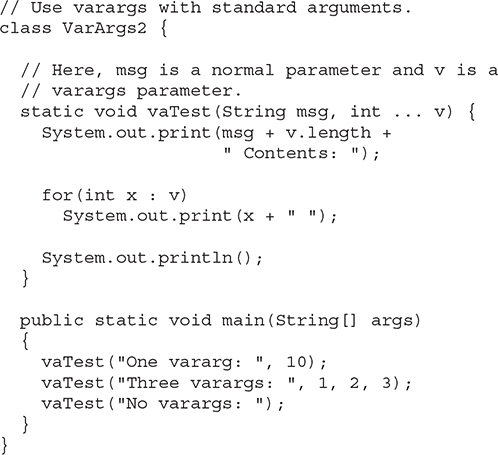

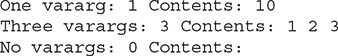

Here is a reworked version of the vaTest( ) method that takes a regular argument and a variable-length argument:

The output from this program is shown here:

# Overloading Vararg Methods

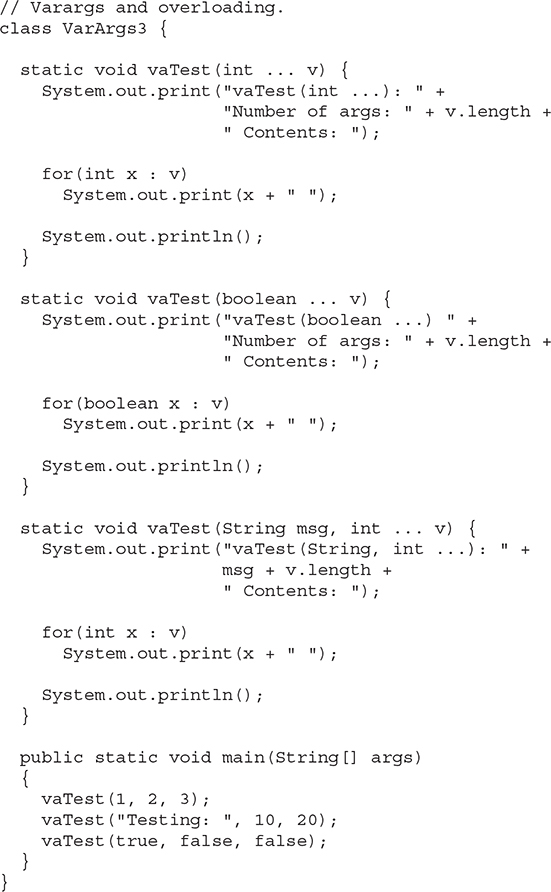

You can overload a method that takes a variable-length argument. For example, the following program overloads vaTest( ) three times:

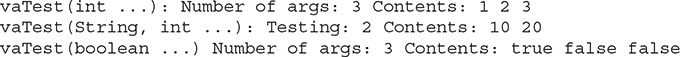

The output produced by this program is shown here:

This program illustrates both ways that a varargs method can be overloaded. First, the types of its vararg parameter can differ. This is the case for vaTest(int ...) and vaTest(boolean ...). Remember, the ... causes the parameter to be treated as an array of the specified type. Therefore, just as you can overload methods by using different types of array parameters, you can overload vararg methods by using different types of varargs. In this case, Java uses the type difference to determine which overloaded method to call.

The second way to overload a varargs method is to add one or more normal parameters. This is what was done with vaTest(String, int ...). In this case, Java uses both the number of arguments and the type of the arguments to determine which method to call.

NOTE A varargs method can also be overloaded by a non-varargs method. For example, vaTest(int x) is a valid overload of vaTest( ) in the foregoing program. This version is invoked only when one int argument is present. When two or more int arguments are passed, the varargs version vaTest (int…v) is used.

# Varargs and Ambiguity

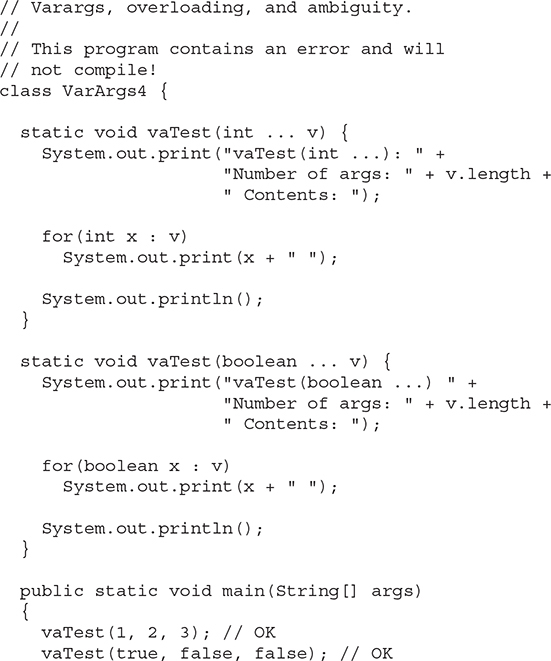

Somewhat unexpected errors can result when overloading a method that takes a variable-length argument. These errors involve ambiguity because it is possible to create an ambiguous call to an overloaded varargs method. For example, consider the following program:

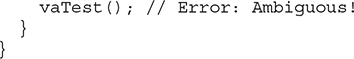

In this program, the overloading of vaTest( ) is perfectly correct. However, this program will not compile because of the following call:

vaTest(); // Error: Ambiguous!

Because the vararg parameter can be empty, this call could be translated into a call to vaTest(int …) or vaTest(boolean …). Both are equally valid. Thus, the call is inherently ambiguous.

Here is another example of ambiguity. The following overloaded versions of vaTest( ) are inherently ambiguous even though one takes a normal parameter:

Although the parameter lists of vaTest( ) differ, there is no way for the compiler to resolve the following call:

vaTest(1)

Does this translate into a call to vaTest(int …), with one varargs argument, or into a call to vaTest(int, int …) with no varargs arguments? There is no way for the compiler to answer this question. Thus, the situation is ambiguous.

Because of ambiguity errors like those just shown, sometimes you will need to forego overloading and simply use two different method names. Also, in some cases, ambiguity errors expose a conceptual flaw in your code, which you can remedy by more carefully crafting a solution.

# Local Variable Type Inference with Reference Types

As you saw in Chapter 3, beginning with JDK 10, Java supports local variable type inference. Recall that when using local variable type inference, the type of the variable is specified as var and the variable must be initialized. Earlier examples have shown type inference with primitive types, but it can also be used with reference types. In fact, type inference with reference types constitutes a primary use. Here is a simple example that declares a String variable called myStr:

var myStr = "This is a string";

Because a quoted string is used as an initializer, the type String is inferred.

As explained in Chapter 3, one of the benefits of local variable type inference is its ability to streamline code, and it is with reference types where such streamlining is most apparent. The reason for this is that many class types in Java have rather long names. For example, in Chapter 13, you will learn about the FileInputStream class, which is used to open a file for input operations. In the past, you would declare and initialize a FileInputStream using a traditional declaration like the one shown here:

FileInputStream fin = new FileInputStream("test.txt");

With the use of var, it can now be written like this:

var fin = new FileInputStream("test.txt");

Here, fin is inferred to be of type FileInputStream because that is the type of its initializer. There is no need to explicitly repeat the type name. As a result, this declaration of fin is substantially shorter than writing it the traditional way. Thus, the use of var streamlines the declaration. This benefit becomes even more apparent in more complex declarations, such as those involving generics. In general, the streamlining attribute of local variable type inference helps lessen the tedium of entering long type names into your program.

Of course, the streamlining aspect of local variable type inference must be used carefully to avoid reducing the readability of your program and, thus, obscuring its meaning. For example, consider a declaration such as the one shown here:

var x = o.getNext();

In this case, it may not be immediately clear to someone reading your code what the type of x is. In essence, local variable type inference is a feature that you should use wisely.

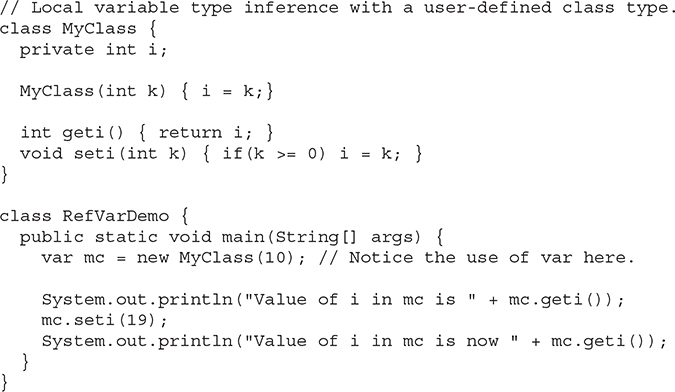

As you would expect, you can also use local variable type inference with user-defined classes, as the following program illustrates. It creates a class called MyClass and then uses local variable type inference to declare and initialize an object of that class.

The output of the program is shown here:

In the program, pay special attention to this line:

var mc = new MyClass(10); // Notice the use of var here.

Here, the type of mc will be inferred as MyClass because that is the type of the initializer, which is a new MyClass object.

As explained earlier in this book, for the benefit of readers working in Java environments that do not support local variable type inference, it will not be used by most examples in the remainder of this edition of this book. This way, the majority of examples will compile and run for the largest number of readers.