# Modules

JDK 9 introduced a new and important feature called modules. Modules give you a way to describe the relationships and dependencies of the code that comprises an application. Modules also let you control which parts of a module are accessible to other modules and which are not. Through the use of modules you can create more reliable, scalable programs.

As a general rule, modules are most helpful to large applications because they help reduce the management complexity often associated with a large software system. However, small programs also benefit from modules because the Java API library has now been organized into modules. Thus, it is now possible to specify which parts of the API are required by your program and which are not. This makes it possible to deploy programs with a smaller run-time footprint, which is especially important when creating code for small devices, such as those intended to be part of the Internet of Things (IoT).

Support for modules is provided both by language elements, including several keywords, and by enhancements to javac, java, and other JDK tools. Furthermore, new tools and file formats were introduced. As a result, the JDK and the run-time system were substantially upgraded to support modules. In short, modules constitute a major addition to, and evolution of, the Java language.

# Module Basics

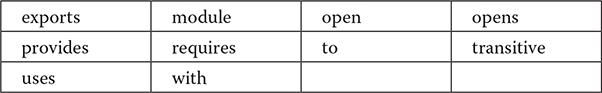

In its most fundamental sense, a module is a grouping of packages and resources that can be collectively referred to by the module’s name. A module declaration specifies the name of a module and defines the relationship a module and its packages have to other modules. Module declarations are program statements in a Java source file and are supported by several module-related keywords. They are shown here:

It is important to understand that these keywords are recognized as keywords only in the context of a module declaration. Otherwise, they are interpreted as identifiers in other situations. Thus, the keyword module could, for example, also be used as a parameter name, although such a use is certainly not recommended. However, making the module-related keywords context-sensitive prevents problems with pre-existing code that may use one or more of them as identifiers.

A module declaration is contained in a file called module-info.java. Thus, a module is defined in a Java source file. This file is then compiled by javac into a class file and is known as its module descriptor. The module-info.java file must contain only a module definition. It cannot contain other types of declarations.

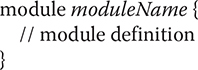

A module declaration begins with the keyword module. Here is its general form:

The name of the module is specified by moduleName, which must be a valid Java identifier or a sequence of identifiers separated by periods. The module definition is specified within the braces. Although a module definition may be empty (which results in a declaration that simply names the module), typically it specifies one or more clauses that define the characteristics of the module.

# A Simple Module Example

At the foundation of a module’s capabilities are two key features. The first is a module’s ability to specify that it requires another module. In other words, one module can specify that it depends on another. A dependence relationship is specified by use of a requires statement. By default, the presence of the required module is checked at both compile time and at run time. The second key feature is a module’s ability to control which, if any, of its packages are accessible by another module. This is accomplished by use of the exports keyword. The public and protected types within a package are accessible to other modules only if they are explicitly exported. Here we will develop an example that introduces both of these features.

The following example creates a modular application that demonstrates some simple mathematical functions. Although this application is purposely very small, it illustrates the core concepts and procedures required to create, compile, and run module-based code. Furthermore, the general approach shown here also applies to larger, real-world applications. It is strongly recommended that you work through the example on your computer, carefully following each step.

NOTE This chapter shows the process of creating, compiling, and running module-based code by use of the command-line tools. This approach has two advantages. First, it works for all Java programmers because no IDE is required. Second, it very clearly shows the fundamentals of the module system, including how it utilizes directories. To follow along, you will need to manually create a number of directories and ensure that each file is placed in its proper directory. As you might expect, when creating real-world, module-based applications, you will likely find a module-aware IDE easier to use because, typically, it will automate much of the process. However, learning the fundamentals of modules using the command-line tools ensures that you have a solid understanding of the topic.

The application defines two modules. The first module is called appstart. It contains a package called appstart.mymodappdemo that defines the application’s entry point in a class called MyModAppDemo. Thus, MyModAppDemo contains the application’s main( ) method. The second module is called appfuncs. It contains a package called appfuncs.simplefuncs that includes the class SimpleMathFuncs. This class defines three static methods that implement some simple mathematical functions. The entire application will be contained in a directory tree that begins at mymodapp.

Before continuing, a few words about module names are appropriate. First, in the examples that follow, the name of a module (such as appfuncs) is the prefix of the name of a package (such as appfuncs.simplefuncs) that it contains. This is not required, but it’s used here as a way of clearly indicating to what module a package belongs. In general, when learning about and experimenting with modules, short, simple names, such as those used in this chapter, are helpful, and you can use any sort of convenient names that you like. However, when creating modules suitable for distribution, you must be careful with the names you choose because you will want those names to be unique. At the time of this writing, the suggested way to achieve this is to use the reverse domain name method. In this method, the reverse domain name of the domain that “owns” the project is used as a prefix for the module. For example, a project associated with hotburgers.com (opens new window) would use com.hotburgers as the module prefix. (The same goes for package names.) Because naming conventions may evolve over time, you will want to check the Java documentation for current recommendations.

Let’s now begin. Start by creating the necessary source code directories by following these steps:

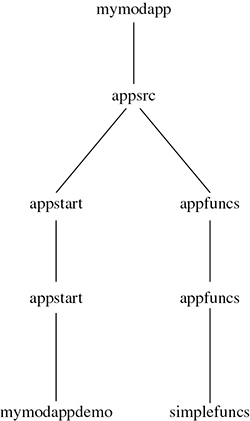

Create a directory called mymodapp. This is the top-level directory for the entire application.

Under mymodapp, create a subdirectory called appsrc. This is the top-level directory for the application’s source code.

Under appsrc, create the subdirectory appstart. Under this directory, create a subdirectory also called appstart. Under this directory, create the directory mymodappdemo. Thus, beginning with appsrc, you will have created this tree:

appsrc\appstart\appstart\mymodappdemo

- Also under appsrc, create the subdirectory appfuncs. Under this directory, create a subdirectory also called appfuncs. Under this directory, create the directory called simplefuncs. Thus, beginning with appsrc, you will have created this tree:

appsrc\appfuncs\appfuncs\simplefuncs

Your directory tree should look like that shown here.

After you have set up these directories, you can create the application’s source files.

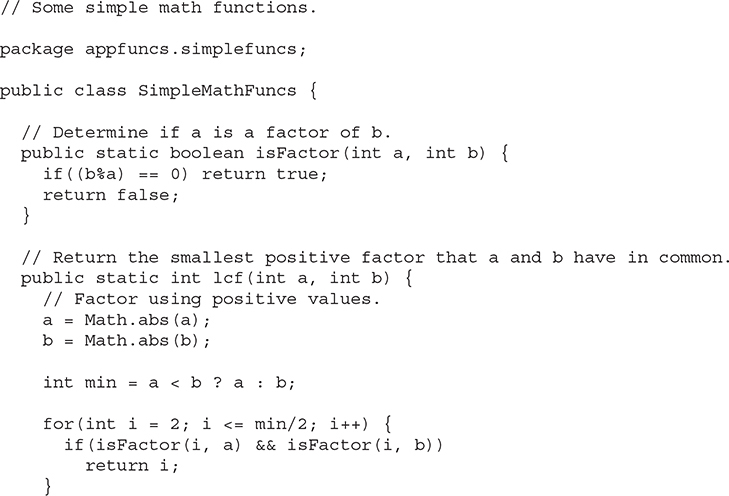

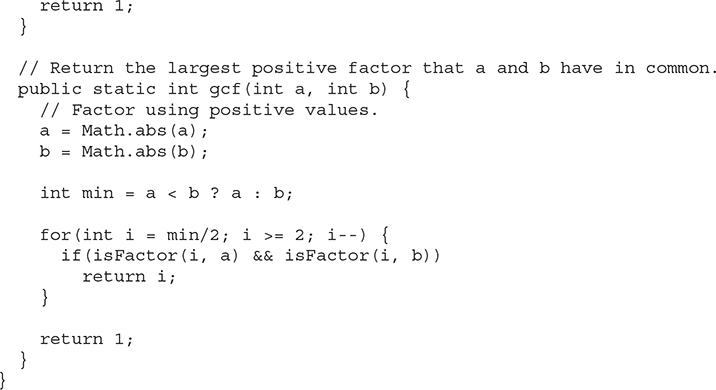

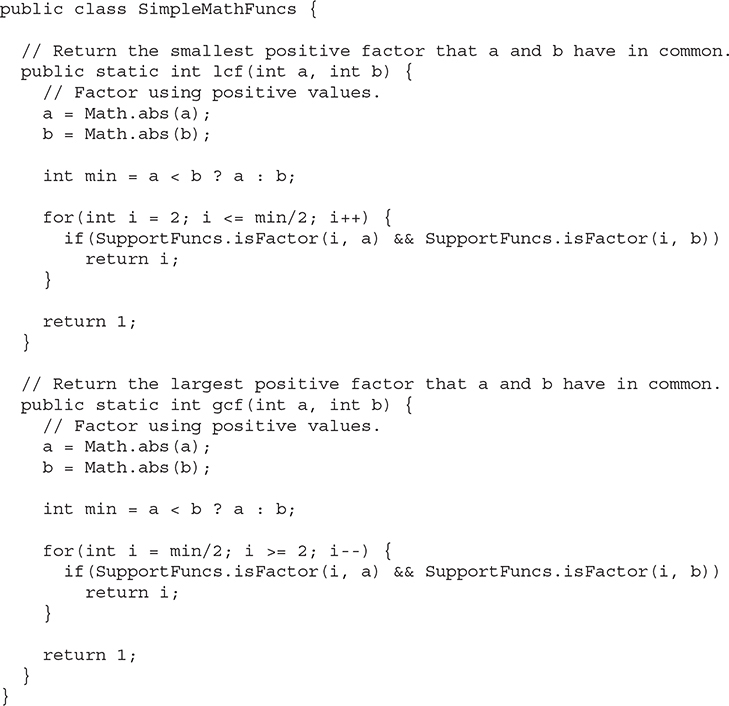

This example will use four source files. Two are the source files that define the application. The first is SimpleMathFuncs.java, shown here. Notice that SimpleMathFuncs is packaged in appfuncs.simplefuncs.

SimpleMathFuncs defines three simple static math functions. The first, isFactor( ), returns true if a is a factor of b. The lcf( ) method returns the smallest factor common to both a and b. In other words, it returns the least common factor of a and b. The gcf( ) method returns the greatest common factor of a and b. In both cases, 1 is returned if no common factors are found. This file must be put in the following directory:

appsrc\appfuncs\appfuncs\simplefuncs

This is the appfuncs.simplefuncs package directory.

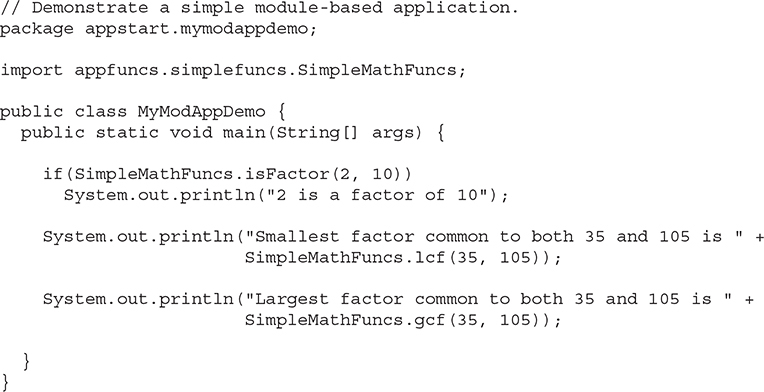

The second source file is MyModAppDemo.java, shown next. It uses the methods in SimpleMathFuncs. Notice that it is packaged in appstart.mymodappdemo. Also note that it imports the SimpleMathFuncs class because it depends on SimpleMathFuncs for its operation.

This file must be put in the following directory:

appsrc\appstart\appstart\mymodappdemo

This is the directory for the appstart.mymodappdemo package.

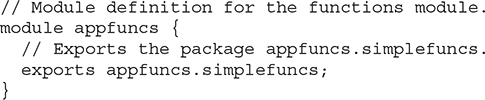

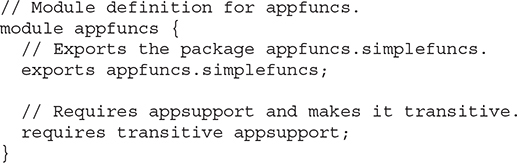

Next, you will need to add module-info.java files for each module. These files contain the module definitions. First, add this one, which defines the appfuncs module:

Notice that appfuncs exports the package appfuncs.simplefuncs, which makes it accessible to other modules. This file must be put into this directory:

appsrc\appfuncs

Thus, it goes in the appfuncs module directory, which is above the package directories.

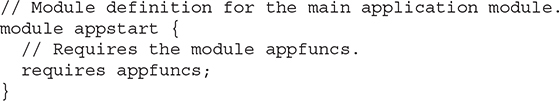

Finally, the module-info.java file for the appstart module is shown next. Notice that appstart requires the module appfuncs.

This file must be put into its module directory:

appsrc\appstart

Before examining the requires, exports, and module statements more closely, let’s first compile and run this example. Be sure that you have correctly created the directories and entered each file into its proper directory, as just explained.

# Compile and Run the First Module Example

Beginning with JDK 9, javac has been updated to support modules. Thus, like all other Java programs, module-based programs are compiled using javac. The process is easy, with the primary difference being that you will usually explicitly specify a module path. A module path tells the compiler where the compiled files will be located. When following along with this example, be sure that you execute the javac commands from the mymodapp directory in order for the paths to be correct. Recall that mymodapp is the top-level directory for the entire module application.

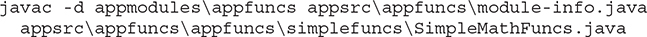

To begin, compile SimpleMathFuncs.java using this command:

Remember, this command must be executed from the mymodapp directory. Notice the use of the -d option. This tells javac where to put the output .class file. For the examples in this chapter, the top of the directory tree for compiled code is appmodules. This command will create the output package directories for appfuncs.simplefuncs under appmodules\appfuncs as needed.

Next, here is the javac command that compiles the module-info.java file for the appfuncs module:

javac -d appmodules\appfuncs appsrc\appfuncs\module-info.java

This puts the module-info.class file into the appmodules\appfuncs directory.

Although the preceding two-step process works, it was shown primarily for the sake of discussion. It is usually easier to compile a module’s module-info.java file and its source files in one command line. Here, the preceding two javac commands are combined into one:

In this case, each compiled file is put in its proper module or package directory.

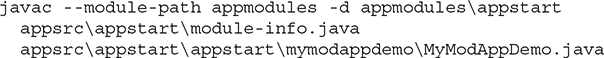

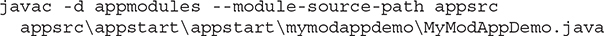

Now, compile module-info.java and MyModAppDemo.java for the appstart module, using this command:

Notice the --module-path option. It specifies the module path, which is the path on which the compiler will look for the user-defined modules required by the module-info.java file. In this case, it will look for the appfuncs module because it is needed by the appstart module. Also, notice that it specifies the output directory as appmodules\appstart. This means that the module-info.class file will be in the appmodules\appstart module directory and MyModAppDemo.class will be in the appmodules\appstart\appstart\mymodappdemo package directory.

Once you have completed the compilation, you can run the application with this java command:

java --module-path appmodules -m appstart/appstart.mymodappdemo.MyModAppDemo

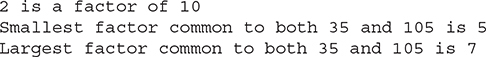

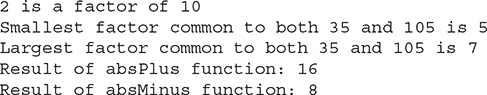

Here, the --module-path option specifies the path to the application’s modules. As mentioned, appmodules is the directory at the top of the compiled modules tree. The -m option specifies the class that contains the entry point of the application and, in this case, the name of the class that contains the main( ) method. When you run the program, you will see the following output:

# A Closer Look at requires and exports

The preceding module-based example relies on the two foundational features of the module system: the ability to specify a dependence and the ability to satisfy that dependence. These capabilities are specified through the use of the requires and exports statements within a module declaration. Each merits a closer examination at this time.

Here is the form of the requires statement used in the example:

requires moduleName;

Here, moduleName specifies the name of a module that is required by the module in which the requires statement occurs. This means that the required module must be present in order for the current module to compile. In the language of modules, the current module is said to read the module specified in the requires statement. When more than one module is required, it must be specified in its own requires statement. Thus, a module declaration may include several different requires statements. In general, the requires statement gives you a way to ensure that your program has access to the modules that it needs.

Here is the general form of the exports statement used in the example:

exports packageName;

Here, packageName specifies the name of the package that is exported by the module in which this statement occurs. A module can export as many packages as needed, with each one specified in a separate exports statement. Thus, a module may have several exports statements.

When a module exports a package, it makes all of the public and protected types in the package accessible to other modules. Furthermore, the public and protected members of those types are also accessible. However, if a package within a module is not exported, then it is private to that module, including all of its public types. For example, even though a class is declared as public within a package, if that package is not explicitly exported by an exports statement, then that class is not accessible to other modules. It is important to understand that the public and protected types of a package, whether exported or not, are always accessible within that package’s module. The exports statement simply makes them accessible to outside modules. Thus, any nonexported package is only for the internal use of its module.

The key to understanding requires and exports is that they work together. If one module depends on another, then it must specify that dependence with requires. The module on which another depends must explicitly export (i.e., make accessible) the packages that the dependent module needs. If either side of this dependence relationship is missing, the dependent module will not compile. As it relates to the foregoing example, MyModAppDemo uses the functions in SimpleMathFuncs. As a result, the appstart module declaration contains a requires statement that names the appfuncs module. The appfuncs module declaration exports the appfuncs.simplefuncs package, thus making the public types in the SimpleMathFuncs class available. Since both sides of the dependence relationship have been fulfilled, the application can compile and run. If either is missing, the compilation will fail.

It is important to emphasize that requires and exports statements must occur only within a module statement. Furthermore, a module statement must occur by itself in a file called module-info.java.

# java.base and the Platform Modules

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, beginning with JDK 9, the Java API packages have been incorporated into modules. In fact, the modularization of the API is one of the primary benefits realized by the addition of the modules. Because of their special role, the API modules are referred to as platform modules, and their names all begin with the prefix java. Here are some examples: java.base, java.desktop, and java.xml. By modularizing the API, it becomes possible to deploy an application with only the packages that it requires, rather than the entire Java Runtime Environment (JRE). Because of the size of the full JRE, this is a very important improvement.

The fact that all of the Java API library packages are now in modules gives rise to the following question: How can the main( ) method in MyModAppDemo in the preceding example use System.out.println( ) without specifying a requires statement for the module that contains the System class? Obviously, the program will not compile and run unless System is present. The same question also applies to the use of the Math class in SimpleMathFuncs. The answer to this question is found in java.base.

Of the platform modules, the most important is java.base. It includes and exports those packages fundamental to Java, such as java.lang, java.io, and java.util, among many others. Because of its importance, java.base is automatically accessible to all modules. Furthermore, all other modules automatically require java.base. There is no need to include a requires java.base statement in a module declaration. (As a point of interest, it is not wrong to explicitly specify java.base, it’s just not necessary.) Thus, in much the same way that java.lang is automatically available to all programs without the use of an import statement, the java.base module is automatically accessible to all module-based programs without explicitly requesting it.

Because java.base contains the java.lang package, and java.lang contains the System class, MyModAppDemo in the preceding example can automatically use System.out.println( ) without an explicit requires statement. The same applies to the use of the Math class in SimpleMathFuncs, because the Math class is also in java.lang. As you will see when you begin to create your own module-based applications, many of the API classes you will commonly need are in the packages included in java.base. Thus, the automatic inclusion of java.base simplifies the creation of module-based code because Java’s core packages are automatically accessible.

One last point: Beginning with JDK 9, the documentation for the Java API now tells you the name of the module in which a package is contained. If the module is java.base, then you can use the contents of that package directly. Otherwise, your module declaration must include a requires clause for the desired module.

# Legacy Code and the Unnamed Module

Another question may have occurred to you when working through the first sample module program. Because Java now supports modules, and the API packages are also contained in modules, why do all of the other programs in the preceding chapters compile and run without error even though they do not use modules? More generally, since there is now over 20 years of Java code in existence and (at the time of this writing) the vast majority of that code does not use modules, how is it possible to compile, run, and maintain that legacy code with a JDK 9 or later compiler? Given Java’s original philosophy of “write once, run everywhere,” this is a very important question because backward capability must be maintained. As you will see, Java answers this question by providing an elegant, nearly transparent means of ensuring backward compatibility with pre-existing code.

Support for legacy code is provided by two key features. The first is the unnamed module. When you use code that is not part of a named module, it automatically becomes part of the unnamed module. The unnamed module has two important attributes. First, all of the packages in the unnamed module are automatically exported. Second, the unnamed module can access any and all other modules. Thus, when a program does not use modules, all API modules in the Java platform are automatically accessible through the unnamed module.

The second key feature that supports legacy code is the automatic use of the class path, rather than the module path. When you compile a program that does not use modules, the class path mechanism is employed, just as it has been since Java’s original release. As a result, the program is compiled and run in the same way it was prior to the advent of modules.

Because of the unnamed module and the automatic use of the class path, there was no need to declare any modules for the sample programs shown elsewhere in this book. They run properly whether you compile them with a modern compiler or an earlier one, such as JDK 8. Thus, even though modules are a feature that has significant impact on Java, compatibility with legacy code is maintained. This approach also provides a smooth, nonintrusive, nondisruptive transition path to modules. Thus, it enables you to move a legacy application to modules at your own pace. Furthermore, it allows you to avoid the use of modules when they are not needed.

Before moving on, an important point needs to be made. For the types of sample programs used elsewhere in this book, and for sample programs in general, there is no benefit in using modules. Modularizing them would simply add clutter and complicate them for no reason or benefit. Furthermore, for many simple programs, there is no need to contain them in modules. For the reasons stated at the start of this chapter, modules are often of the greatest benefit when creating commercial programs. Therefore, no examples outside this chapter will use modules. This also allows the examples to be compiled and run in a pre–JDK 9 environment, which is important to readers using an older version of Java. Thus, except for the examples in this chapter, the examples in this book work for both pre-module and post-module JDKs.

# Exporting to a Specific Module

The basic form of the exports statement makes a package accessible to any and all other modules. This is often exactly what you want. However, in some specialized development situations, it can be desirable to make a package accessible to only a specific set of modules, not all other modules. For example, a library developer might want to export a support package to certain other modules within the library, but not make it available for general use. Adding a to clause to the exports statement provides a means by which this can be accomplished.

In an exports statement, the to clause specifies a list of one or more modules that have access to the exported package. Furthermore, only those modules named in the to clause will have access. In the language of modules, the to clause creates what is known as a qualified export.

The form of exports that includes to is shown here:

exports packageName to moduleNames;

Here, moduleNames is a comma-separated list of modules to which the exporting module grants access.

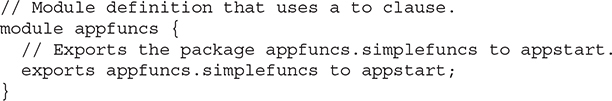

You can try the to clause by changing the module-info.java file for the appfuncs module, as shown here:

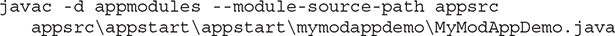

Now, simplefuncs is exported only to appstart and to no other modules. After making this change, you can recompile the application by using this javac command:

After compiling, you can run the application as shown earlier.

This example also uses another module-related feature. Look closely at the preceding javac command. First, notice that it specifies the --module-source-path option. The module source path specifies the top of the module source tree. The --module-source-path option automatically compiles the files in the tree under the specified directory, which is appsrc in this example. The --module-source-path option must be used with the -d option to ensure that the compiled modules are stored in their proper directories under appmodules. This form of javac is called multi-module mode because it enables more than one module to be compiled at a time. The multi-module compilation mode is especially helpful here because the to clause refers to a specific module, and the requiring module must have access to the exported package. Thus, in this case, both appstart and appfuncs are needed to avoid warnings and/or errors during compilation. Multi-module mode avoids this problem because both modules are being compiled at the same time.

The multi-module mode of javac has another advantage. It automatically finds and compiles all source files for the application, creating the necessary output directories. Because of the advantages that multi-module compilation mode offers, it will be used for the subsequent examples.

NOTE As a general rule, qualified export is a special case feature. Most often, your modules will either provide unqualified export of a package or not export the package at all, keeping it inaccessible. As such, qualified export is discussed here primarily for the sake of completeness. Also, qualified export by itself does not prevent the exported package from being misused by malicious code in a module that masquerades as the targeted module. The security techniques required to prevent this from happening are beyond the scope of this book. Consult the Oracle documentation for details on security in this regard, and Java security details in general.

# Using requires transitive

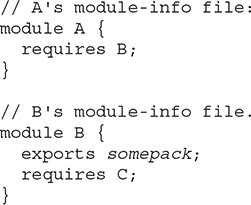

Consider a situation in which there are three modules, A, B, and C, that have the following dependences:

• A requires B.

• B requires C.

Given this situation, it is clear that since A depends on B and B depends on C, A has an indirect dependence on C. As long as A does not directly use any of the contents of C, then you can simply have A require B in its module-info file, and have B export the packages required by A in its module-info file, as shown here:

Here, somepack is a placeholder for the package exported by B and used by A. Although this works as long as A does not need to use anything defined in C, a problem occurs if A does want to access a type in C. In this case, there are two solutions.

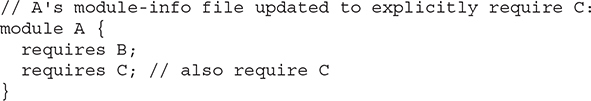

The first solution is to simply add a requires C statement to A’s file, as shown here:

This solution certainly works, but if B will be used by many modules, you must add requires C to all module definitions that require B. This is not only tedious, it is also error prone. Fortunately, there is a better solution. You can create an implied dependence on C. Implied dependence is also referred to as implied readability.

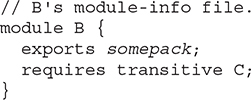

To create an implied dependence, add the transitive keyword after requires in the clause that requires the module upon which an implied readability is needed. In the case of this example, you would change B’s module-info file as shown here:

Here, C is now required as transitive. After making this change, any module that depends on B will also, automatically, depend on C. Thus, A would automatically have access to C.

You can experiment with requires transitive by reworking the preceding modular application example so that the isFactor( ) method is removed from the SimpleMathFuncs class in the appfuncs.simplefuncs package and put into a new class, module, and package. The new class will be called SupportFuncs, the module will be called appsupport, and the package will be called appsupport.supportfuncs. The appfuncs module will then add a dependence on the appsupport module by use of requires transitive. This will enable both the appfuncs and appstart modules to access it without appstart having to provide its own requires statement. This works because appstart receives access to it through an appfuncs requires transitive statement. The following describes the process in detail.

To begin, create the source directories that support the new appsupport module. First, create appsupport under the appsrc directory. This is the module directory for the support functions. Under appsupport, create the package directory by adding the appsupport subdirectory followed by the supportfuncs subdirectory. Thus, the directory tree for appsupport should now look like this:

appsrc\appsupport\appsupport\supportfuncs

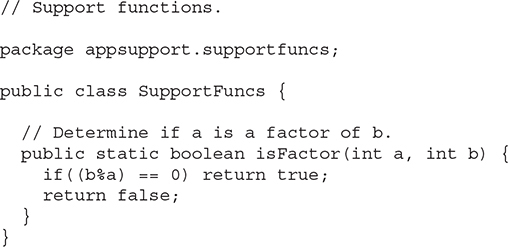

Once the directories have been established, create the SupportFuncs class. Notice that SupportFuncs is part of the appsupport.supportfuncs package. Therefore, you must put it in the appsupport.supportfuncs package directory.

Notice that isFactor( ) is now part of SupportFuncs, rather than SimpleMathFuncs.

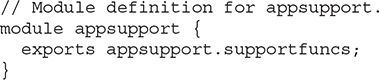

Next, create the module-info.java file for the appsupport module and put it in the appsrc\appsupport directory.

As you can see, it exports the appsupport.supportfuncs package.

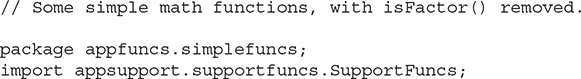

Because isFactor( ) is now part of Supportfuncs, remove it from SimpleMathFuncs. Thus, SimpleMathFuncs.java will now look like this:

Notice that now the SupportFuncs class is imported and calls to isFactor( ) are referred to through the class name SupportFuncs.

Next, change the module-info.java file for appfuncs so that in its requires statement, appsupport is specified as transitive, as shown here:

Because appfuncs requires appsupport as transitive, there is no need for the module-info.java file for appstart to also require it. Its dependence on appsupport is implied. Thus, no changes to the module-info.java file for appstart are needed.

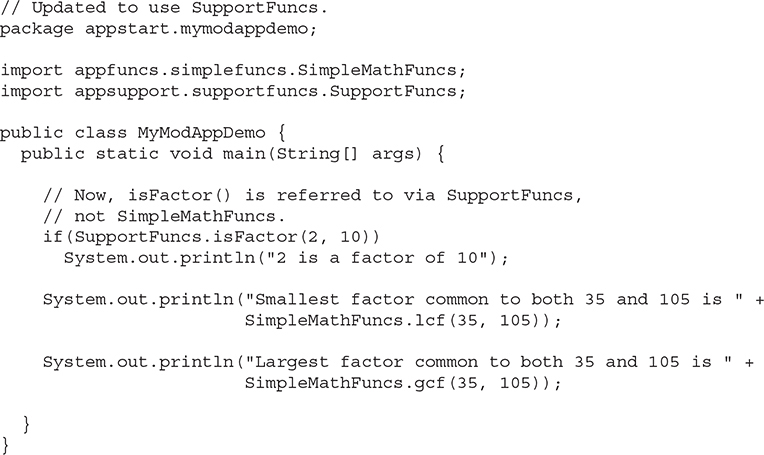

Finally, update MyModAppDemo.java to reflect these changes. Specifically, it must now import the SupportFuncs class and specify it when invoking isFactor( ), as shown here:

Once you have completed all of the preceding steps, you can recompile the entire program using this multi-module compilation command:

As explained earlier, the multi-module compilation will automatically create the parallel module subdirectories, under the appmodules directory.

You can run the program using this command:

java --module-path appmodules -m appstart/appstart.mymodappdemo.MyModAppDemo

It will produce the same output as the previous version. However, this time three different modules are required.

To prove that the transitive modifier is actually required by the application, remove it from the module-info.java file for appfuncs. Then, try to compile the program. As you will see, an error will result because appsupport is no longer accessible by appstart.

Here is another experiment. In the module-info file for appsupport, try exporting the appsupport.supportfuncs package to only appfuncs by use of a qualified export, as shown here:

exports appsupport.supportfuncs to appfuncs;

Next, attempt to compile the program. As you see, the program will not compile because now the support function isFactor( ) is not available to MyModAppDemo, which is in the appstart module. As explained previously, a qualified export restricts access to a package to only those modules specified by the to clause.

One final point: because of a special exception in the Java language syntax, in a requires statement, if transitive is immediately followed by a separator (such as a semicolon), it is interpreted as an identifier (for example, as a module name) rather than a keyword.

# Use Services

In programming, it is often useful to separate what must be done from how it is done. As you learned in Chapter 9, one way this is accomplished in Java is through the use of interfaces. The interface specifies the what, and the implementing class specifies the how. This concept can be expanded so that the implementing class is provided by code that is outside your program, through the use of a plug-in. Using such an approach, the capabilities of an application can be enhanced, upgraded, or altered by simply changing the plug-in. The core of the application itself remains unchanged. One way that Java supports a pluggable application architecture is through the use of services and service providers. Because of their importance, especially in large, commercial applications, Java’s module system provides support for them.

Before we begin, it is necessary to state that applications that use services and service providers are typically fairly sophisticated. Therefore, you may find that you do not often need the service-based module features. However, because support for services constitutes a rather significant part of the module system, it is important that you have a general understanding of how these features work. Also, a simple example is presented that illustrates the core techniques needed to use them.

# Service and Service Provider Basics

In Java, a service is a program unit whose functionality is defined by an interface or abstract class. Thus, a service specifies in a general way some form of program activity. A concrete implementation of a service is supplied by a service provider. In other words, a service defines the form of some action, and the service provider supplies that action.

As mentioned, services are often used to support a pluggable architecture. For example, a service might be used to support the translation of one language into another. In this case, the service supports translation in general. The service provider supplies a specific translation, such as German to English or French to Chinese. Because all service providers implement the same interface, different translators can be used to translate different languages without having to change the core of the application. You can simply change the service provider.

Service providers are supported by the ServiceLoader class. ServiceLoader is a generic class packaged in java.util. It is declared like this:

class ServiceLoader<S>

Here, S specifies the service type. Service providers are loaded by the load( ) method. It has several forms; the one we will use is shown here:

public static <S> ServiceLoader<S> load(Class <S> serviceType)

Here, serviceType specifies the Class object for the desired service type. Recall that Class is a class that encapsulates information about a class. There are a variety of ways to obtain a Class instance. The way we will use here involves a class literal. Recall that a class literal has this general form:

className.class

Here, className specifies the name of the class.

When load( ) is called, it returns a ServiceLoader instance for the application. This object supports iteration and can be cycled through by use of a for-each for loop. Therefore, to find a specific provider, simply search for it using a loop.

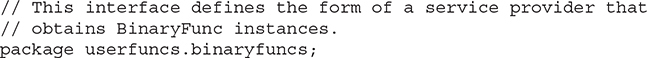

# The Service-Based Keywords

Modules support services through the use of the keywords provides, uses, and with. Essentially, a module specifies that it provides a service with a provides statement. A module indicates that it requires a service with a uses statement. The specific type of service provider is declared by with. When used together, they enable you to specify a module that provides a service, a module that needs that service, and the specific implementation of that service. Furthermore, the module system ensures that the service and service providers are available and will be found.

Here is the general form of provides:

provides serviceType with implementationTypes;

Here, serviceType specifies the type of the service, which is often an interface, although abstract classes are also used. A comma-separated list of the implementation types is specified by implementationTypes. Therefore, to provide a service, the module indicates both the name of the service and its implementation.

Here is the general form of the uses statement:

uses serviceType;

Here, serviceType specifies the type of the service required.

# A Module-Based Service Example

To demonstrate the use of services, we will add a service to the modular application example that we have been evolving. For simplicity, we will begin with the first version of the application shown at the start of this chapter. To it we will add two new modules. The first is called userfuncs. It will define interfaces that support functions that perform binary operations in which each argument is an int and the result is an int. The second module is called userfuncsimp, and it contains concrete implementations of the interfaces.

Begin by creating the necessary source directories:

Under the appsrc directory, add directories called userfuncs and userfuncsimp.

Under userfuncs, add the subdirectory also called userfuncs. Under that directory, add the subdirectory binaryfuncs. Thus, beginning with appsrc, you will have created this tree:

appsrc\userfuncs\userfuncs\binaryfuncs

- Under userfuncsimp, add the subdirectory also called userfuncsimp. Under that directory, add the subdirectory binaryfuncsimp. Thus, beginning with appsrc, you will have created this tree:

appsrc\userfuncsimp\userfuncsimp\binaryfuncsimp

This example expands the original version of the application by providing support for functions beyond those built into the application. Recall that the SimpleMathFuncs class supplies three built-in functions: isFactor( ), lcf( ), and gcf( ). Although it would be possible to add more functions to this class, doing so requires modifying and recompiling the application. By implementing services, it becomes possible to “plug in” new functions at run time, without modifying the application, and that is what this example will do. In this case, the service supplies functions that take two int arguments and return an int result. Of course, other types of functions can be supported if additional interfaces are provided, but support for binary integer functions is sufficient for our purposes and keeps the source code size of the example manageable.

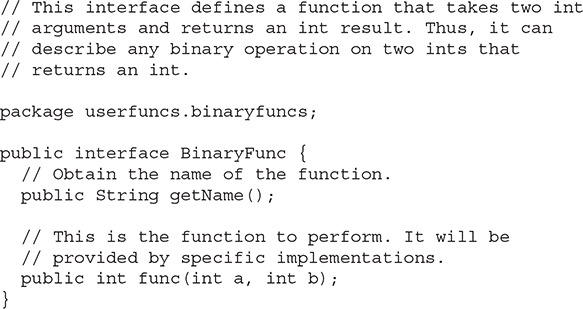

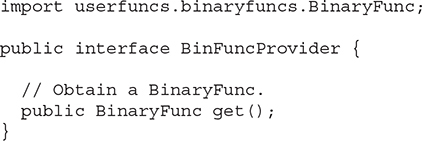

# The Service Interfaces

Two service-related interfaces are needed. One specifies the form of an action, and the other specifies the form of the provider of that action. Both go in the binaryfuncs directory, and both are in the userfuncs.binaryfuncs package. The first, called BinaryFunc, declares the form of a binary function. It is shown here:

BinaryFunc declares the form of an object that can implement a binary integer function. This is specified by the func( ) method. The name of the function is obtainable from getName( ). The name will be used to determine what type of function is implemented. This interface is implemented by a class that supplies a binary function.

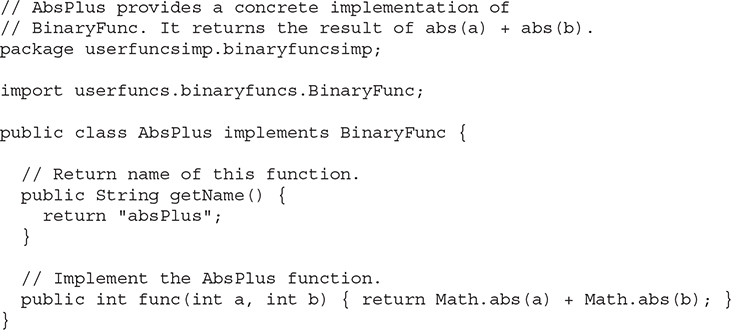

The second interface declares the form of the service provider. It is called BinFuncProvider and is shown here:

BinFuncProvider declares only one method, get( ), which is used to obtain an instance of BinaryFunc. This interface must be implemented by a class that wants to provide instances of BinaryFunc.

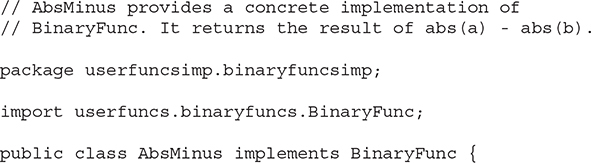

# The Implementation Classes

In this example, two concrete implementations of BinaryFunc are supported. The first is AbsPlus, which returns the sum of the absolute values of its arguments. The second is AbsMinus, which returns the result of subtracting the absolute value of the second argument from the absolute value of the first argument. These are provided by the classes AbsPlusProvider and AbsMinusProvider. The source code for these classes must be stored in the binaryfuncsimp directory, and they are all part of the userfuncsimp.binaryfuncsimp package.

The code for AbsPlus is shown here:

AbsPlus implements func( ) such that it returns the result of adding the absolute values of a and b. Notice that getName( ) returns the "absPlus" string. It identifies this function.

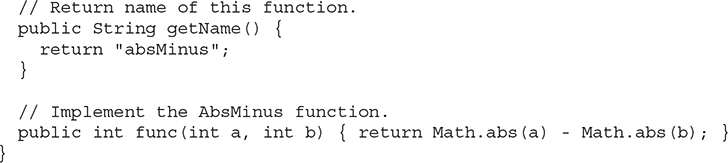

The AbsMinus class is shown next:

Here, func( ) is implemented to return the difference between the absolute values of a and b, and the string "absMinus" is returned by getName( ).

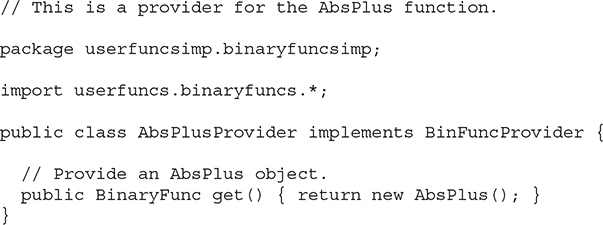

To obtain an instance of AbsPlus, the AbsPlusProvider is used. It implements BinFuncProvider and is shown here:

The get( ) method simply returns a new AbsPlus( ) object. Although this provider is very simple, it is important to point out that some service providers will be much more complex.

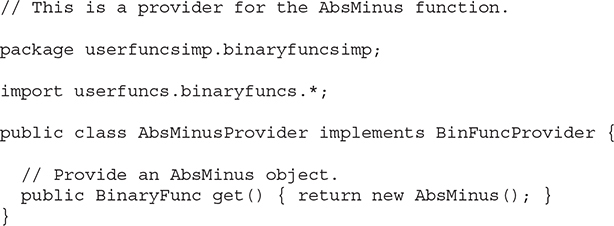

The provider for AbsMinus is called AbsMinusProvider and is shown next:

Its get( ) method returns an object of AbsMinus.

# The Module Definition Files

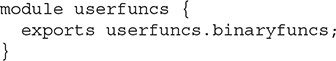

Next, two module definition files are needed. The first is for the userfuncs module. It is shown here:

This code must be contained in a module-info.java file that is in the userfuncs module directory. Notice that it exports the userfuncs.binaryfuncs package. This is the package that defines the BinaryFunc and BinFuncProvider interfaces.

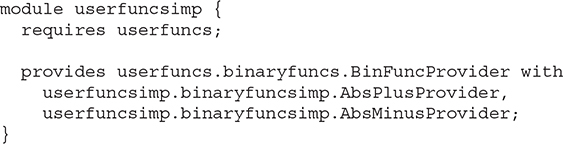

The second module-info.java file is shown next. It defines the module that contains the implementations. It goes in the userfuncsimp module directory.

This module requires userfuncs because that is where BinaryFunc and BinFuncProvider are contained, and those interfaces are needed by the implementations. The module provides BinFuncProvider implementations with the classes AbsPlusProvider and AbsMinusProvider.

# Demonstrate the Service Providers in MyModAppDemo

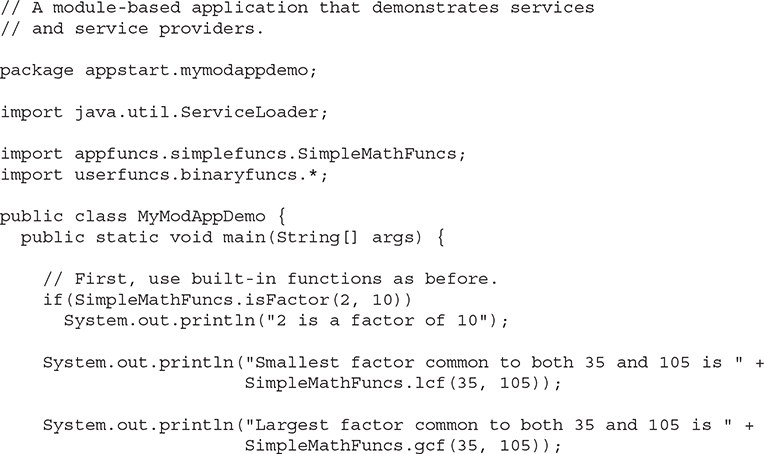

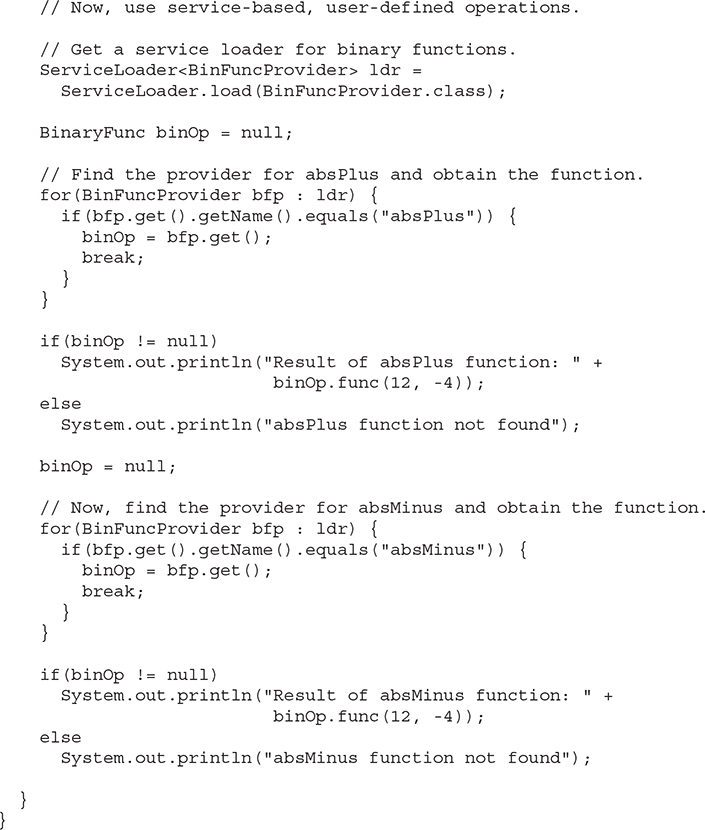

To demonstrate the use of the services, the main( ) method of MyModAppDemo is expanded to use AbsPlus and AbsMinus. It does so by loading them at run time by use of ServiceLoader.load( ). Here is the updated code:

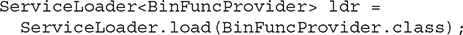

Let’s take a close look at how a service is loaded and executed by the preceding code. First, a service loader for services of type BinFuncProvider is created with this statement:

Notice that the type parameter to ServiceLoader is BinFuncProvider. This is also the type used in the call to load( ). This means that providers that implement this interface will be found. Thus, after this statement executes, BinFuncProvider classes in the module will be available through ldr. In this case, both AbsPlusProvider and AbsMinusProvider will be available.

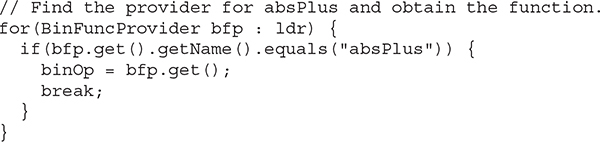

Next, a reference of type BinaryFunc called binOp is declared and initialized to null. It will be used to refer to an implementation that supplies a specific type of binary function. Next, the following loop searches ldr for one that has the "absPlus" name.

Here, a for-each loop iterates through ldr. Inside the loop, the name of the function supplied by the provider is checked. If it matches "absPlus", that function is assigned to binOp by calling the provider’s get( ) method.

Finally, if the function is found, as it will be in this example, it is executed by this statement:

In this case, because binOp refers to an instance of AbsPlus, the call to func( ) performs an absolute value addition. A similar sequence is used to find and execute AbsMinus.

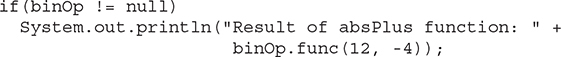

Because MyModAppDemo now uses BinFuncProvider, its module definition file must include a uses statement that specifies this fact. Recall that MyModAppDemo is in the appstart module. Therefore, you must change the module-info.java file for appstart as shown here:

# Compile and Run the Module-Based Service Example

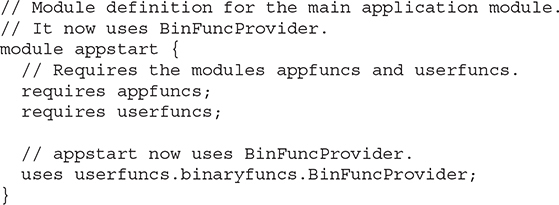

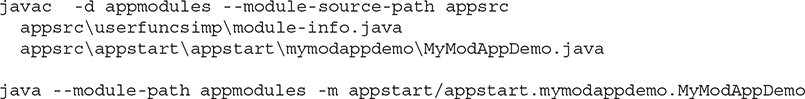

Once you have performed all of the preceding steps, you can compile and run the example by executing the following commands:

Here is the output:

As the output shows, the binary functions were located and executed. It is important to emphasize that if either the provides statement in the userfuncsimp module or the uses statement in the appstart module were missing, the application would fail.

One last point: The preceding example was kept very simple in order to clearly illustrate module support for services, but much more sophisticated uses are possible. For example, you might use a service to provide a sort( ) method that sorts a file. Various sorting algorithms could be supported and made available through the service. The specific sort could then be chosen based on the desired run-time characteristics, the nature and/or size of the data, and whether random access to the data is supported. You might want to try implementing such a service as a way to further experiment with services in modules.

# Module Graphs

A term you are likely to encounter when working with modules is module graph. During compilation, the compiler resolves the dependence relationships between modules by creating a module graph that represents the dependences. The process ensures that all dependences are resolved, including those that occur indirectly. For example, if module A requires module B, and B requires module C, then the module graph will contain module C even if A does not use it directly.

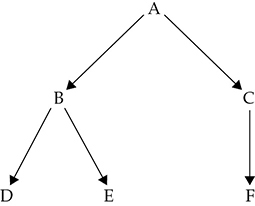

Module graphs can be depicted visually in a drawing to illustrate the relationship between modules. Here is a simple example. Assume six modules called A, B, C, D, E, and F. Further assume that A requires B and C, B requires D and E, and C requires F. The following visually depicts this relationship. (Because java.base is automatically included, it is not shown in the diagram.)

In Java, the arrows point from the dependent module to the required module. Thus, a drawing of a module graph depicts what modules have access to what other modules. Frankly, only the smallest applications can have their module graphs visually represented because of the complexity typically involved in many commercial applications.

# Three Specialized Module Features

The preceding discussions have described the key features of modules supported by the Java language, and they are the features on which you will typically rely when creating your own modules. However, there are three additional module-related features that can be quite useful in certain circumstances. These are the open module, the opens statement, and the use of requires static. Each of these features is designed to handle a specialized situation, and each constitutes a fairly advanced aspect of the module system. That said, it is important for all Java programmers to have a general understanding of their purpose.

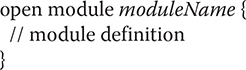

# Open Modules

As you learned earlier in this chapter, by default, the types in a module’s packages are accessible only if they are explicitly exported via an exports statement. While this is usually what you will want, there can be circumstances in which it is useful to enable run-time access to all packages in the module, whether a package is exported or not. To allow this, you can create an open module. An open module is declared by preceding the module keyword with the open modifier, as shown here:

In an open module, types in all its packages are accessible at run time. Understand, however, that only those packages that are explicitly exported are available at compile time. Thus, the open modifier affects only run-time accessibility. The primary reason for an open module is to enable the packages in the module to be accessed through reflection. As explained in Chapter 12, reflection is the feature that lets a program analyze code at run time.

# The opens Statement

It is possible for a module to open a specific package for run-time access by other modules and for reflective access rather than opening an entire module. To do so, use the opens statement, shown here:

opens packageName;

Here, packageName specifies the package to open. It is also possible to include a to clause, which names those modules for which the package is opened.

It is important to understand opens does not grant compile-time access. It is used only to open a package for run-time and reflective access. However, you can both export and open a module. One other point: an opens statement cannot be used in an open module. Remember, all packages in an open module are already open.

# requires static

As you know, requires specifies a dependence that, by default, is enforced both during compilation and at run time. However, it is possible to relax this requirement in such a way that a module is not required at run time. This is accomplished by use of the static modifier in a requires statement. For example, this specifies that mymod is required for compilation, but not at run time:

requires static mymod;

In this case, the addition of static makes mymod optional at run time. This can be helpful in a situation in which a program can utilize functionality if it is present, but not require it.

# Introducing jlink and Module JAR Files

As the preceding discussions have shown, modules represent a substantial enhancement to the Java language. The module system also supports enhancements at run time. One of the most important is the ability to create a run-time image that is specifically tailored to your application. To accomplish this, you can use a JDK tool called jlink. It combines a group of modules into an optimized run-time image. You can use jlink to link modular JAR files, JMOD files, or even modules in their unarchived, “exploded directory” form.

# Linking Files in an Exploded Directory

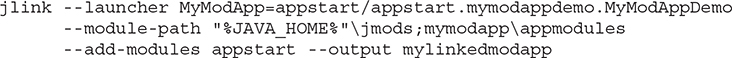

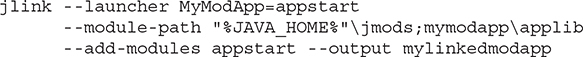

Let’s look first at using jlink to create a run-time image from unarchived modules. That is, the files are contained in their raw form in a fully expanded (i.e., exploded) directory. Assuming a Windows environment, the following command links the modules for the first example in this chapter. It must be executed from a directory directly above mymodapp.

Let’s look closely at this command. First, the option --launcher tells jlink to create a command that starts the application. It specifies the name of the application and the path to the main class. In this case, the main class is MyModAppDemo. The --module-path option specifies the path to the required modules. The first is the path to the platform modules; the second is the path to the application modules. Notice the use of the environmental variable JAVA_HOME. It represents the path to the standard JDK directory. For example, in a standard Windows installation, the path will typically be something similar to "C:\program files"\java\jdk-17\jmods, but the use of JAVA_HOME is both shorter and able to work no matter in what directory the JDK was installed. The --add-modules option specifies the module or modules to add. Notice that only appstart is specified. This is because jlink automatically resolves all dependencies and includes all required modules. Finally, --output specifies the output directory.

After you run the preceding command, a directory called mylinkedmodapp will have been created that contains the run-time image. In its bin directory, you will find a launcher file called MyModApp that you can use to run the application. For example, in Windows, this will be a batch file that executes the program.

# Linking Modular JAR Files

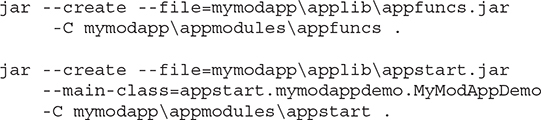

Although linking modules from their exploded directory is convenient, when working on real-world code, you will often be using JAR files. (Recall that JAR stands for _J_ava _AR_chive. It is a file format typically used for application deployment.) In the case of modular code, you will be using modular JAR files. A modular JAR file is one that contains a module-info.class file. Beginning with JDK 9, the jar tool has the ability to create modular JAR files. For example, it can now recognize a module path. Once you have created modular JAR files, you can use jlink to link them into a run-time image. To understand the process, let’s work through an example. Again assuming the first example in this chapter, here are the jar commands that create modular JAR files for the MyModAppDemo program. Each must be executed from a directory directly above mymodapp. Also, you will need to create a directory called applib under mymodapp.

Here, --create tells jar to create a new JAR file. The --file option specifies the name of the JAR file. The files to include are specified by the -C option. The class that contains main( ) is specified by the --main-class option. After running these commands, the JAR files for the application will be in the applib directory under mymodapp.

Given the modular JAR files just created, here is the command that links them:

Here, the module path to the JAR files is specified, not the path to the exploded directories. Otherwise, the jlink command is the same as before.

As a point of interest, you can use the following command to run the application directly from the JAR files. It must be executed from a directory directly above mymodapp.

java -p mymodapp\applib -m appstart

Here, -p specifies the module path, and -m specifies the module that contains the program’s entry point.

# JMOD Files

The jlink tool can also link files that use the newer JMOD format introduced by JDK 9. JMOD files can include things that are not applicable to a JAR file. They are created by the new jmod tool. Although most applications will still use module JAR files, JMOD files will be of value in specialized situations. As a point of interest, beginning with JDK 9, the platform modules are contained in JMOD files.

NOTE jlink can also be used by the recently added jpackage tool. This tool can create a natively installable application.

# A Brief Word About Layers and Automatic Modules

When learning about modules, you are likely to encounter reference to two additional module-related features. These are layers and automatic modules. Both are designed for specialized, advanced work with modules or when migrating preexisting applications. Although it is likely that most programmers will not need to make use of these features, a brief description of each is given here in the interest of completeness.

A module layer associates the modules in a module graph with a class loader. Thus, different layers can use different class loaders. Layers enable certain specialized types of applications to be more easily constructed.

An automatic module is created by specifying a nonmodular JAR file on the module path, with its name being automatically derived. (It is also possible to explicitly specify a name for an automatic module in the manifest file.) Automatic modules enable normal modules to have a dependence on code in the automatic module. Automatic modules are provided as an aid in migration from pre-modular code to fully modular code. Thus, they are primarily a transitional feature.

# Final Thoughts on Modules

The preceding discussions have introduced and demonstrated the core elements of Java’s module system. These are the features about which every Java programmer should have at least a basic understanding. As you might guess, the module system provides additional features that give you fine-grained control over the creation and use of modules. For example, both javac and java have many more options related to modules than described in this chapter. Because modules are a significant addition to Java, it is likely that the module system will evolve over time. You will want to watch for enhancements to this innovative aspect of Java.