# Multithreaded Programming

Java provides built-in support for multithreaded programming. A multithreaded program contains two or more parts that can run concurrently. Each part of such a program is called a thread, and each thread defines a separate path of execution. Thus, multithreading is a specialized form of multitasking.

You are almost certainly acquainted with multitasking because it is supported by virtually all modern operating systems. However, there are two distinct types of multitasking: process-based and thread-based. It is important to understand the difference between the two. For many readers, process-based multitasking is the more familiar form. A process is, in essence, a program that is executing. Thus, process-based multitasking is the feature that allows your computer to run two or more programs concurrently. For example, process-based multitasking enables you to run the Java compiler at the same time that you are using a text editor or visiting a website. In process-based multitasking, a program is the smallest unit of code that can be dispatched by the scheduler.

In a thread-based multitasking environment, the thread is the smallest unit of dispatchable code. This means that a single program can perform two or more tasks simultaneously. For instance, a text editor can format text at the same time that it is printing, as long as these two actions are being performed by two separate threads. Thus, process-based multitasking deals with the “big picture,” and thread-based multitasking handles the details.

Multitasking threads require less overhead than multitasking processes. Processes are heavyweight tasks that require their own separate address spaces. Interprocess communication is expensive and limited. Context switching from one process to another is also costly. Threads, on the other hand, are lighter weight. They share the same address space and cooperatively share the same heavyweight process. Interthread communication is inexpensive, and context switching from one thread to the next is lower in cost. While Java programs make use of process-based multitasking environments, process-based multitasking is not under Java’s direct control. However, multithreaded multitasking is.

Multithreading enables you to write efficient programs that make maximum use of the processing power available in the system. One important way multithreading achieves this is by keeping idle time to a minimum. This is especially important for the interactive, networked environment in which Java operates because idle time is common. For example, the transmission rate of data over a network is much slower than the rate at which the computer can process it. Even local file system resources are read and written at a much slower pace than they can be processed by the CPU. And, of course, user input is much slower than the computer. In a single-threaded environment, your program has to wait for each of these tasks to finish before it can proceed to the next one—even though most of the time the program is idle, waiting for input. Multithreading helps you reduce this idle time because another thread can run when one is waiting.

If you have programmed for operating systems such as Windows, then you are already familiar with multithreaded programming. However, the fact that Java manages threads makes multithreading especially convenient because many of the details are handled for you.

# The Java Thread Model

The Java run-time system depends on threads for many things, and all the class libraries are designed with multithreading in mind. In fact, Java uses threads to enable the entire environment to be asynchronous. This helps reduce inefficiency by preventing the waste of CPU cycles.

The value of a multithreaded environment is best understood in contrast to its counterpart. Single-threaded systems often use an approach called an event loop with polling. In this model, a single thread of control runs in an infinite loop, polling a single event queue to decide what to do next. Once this polling mechanism returns with, say, a signal that a network file is ready to be read, then the event loop dispatches control to the appropriate event handler. Until this event handler returns, nothing else can happen in the program. This wastes CPU time. It can also result in one part of a program dominating the system and preventing any other events from being processed. In general, in a single-threaded environment, when a thread blocks (that is, suspends execution) because it is waiting for some resource, the entire program stops running. This is an example of how only being able to do one thing at a time, something common to all single-threaded systems, whatever approach they use, is an inefficient way to use the CPU.

The benefit of Java’s multithreading is that the main loop/polling mechanism is eliminated. One thread can pause without stopping other parts of your program. For example, the idle time created when a thread reads data from a network or waits for user input can be utilized elsewhere. Multithreading allows animation loops to sleep for a second between each frame without causing the whole system to pause. When a thread blocks in a Java program, only the single thread that is blocked pauses. All other threads continue to run.

As most readers know, over the past few years, multicore systems have become commonplace. Of course, single-core systems are still in use. It is important to understand that Java’s multithreading features work in both types of systems. In a single-core system, concurrently executing threads share the CPU, with each thread receiving a slice of CPU time. Therefore, in a single-core system, two or more threads do not actually run at the same time, but idle CPU time is utilized. However, in multicore systems, it is possible for two or more threads to actually execute simultaneously. In many cases, this can further improve program efficiency and increase the speed of certain operations.

Java has straddled these two CPU architectures with the thread model by implementing Java threads, each as a wrapper around an OS thread. Such Java threads are known as platform threads. For most developers, platform threads, when used correctly, give great scalability and performance characteristics. However, for some high-throughput server applications, particularly ones managing many connections simultaneously like a heavily trafficked web application, this model can lead to performance bottlenecks. For these special kinds of applications, JDK 21 has added a new way to map Java threads onto OS threads. Java threads using this new feature are called virtual threads. When an application uses virtual threads, the JVM is freed from tying each virtual thread one-to-one with an OS thread, offering greater efficiencies for highly multithreaded applications. While most developers will continue to use the default platform thread model, for those who do wish to explore virtual threads, fortunately, the programming model for the new virtual threads is the same as for platform threads. We’ll cover virtual threads at the end of the chapter.

NOTE In addition to the multithreading features described in this chapter, you will also want to explore the Fork/Join Framework. It provides a powerful means of creating multithreaded applications that automatically scale to make best use of multicore environments. The Fork/Join Framework is part of Java’s support for parallel programming, which is the name commonly given to the techniques that optimize some types of algorithms for parallel execution in systems that have more than one CPU. For a discussion of the Fork/Join Framework and other concurrency utilities, see Chapter 29. Java’s traditional multithreading capabilities are described here.

Threads exist in several states. Here is a general description: A thread can be running. It can be ready to run as soon as it gets CPU time. A running thread can be suspended, which temporarily halts its activity. A suspended thread can then be resumed, allowing it to pick up where it left off. A thread can be blocked when waiting for a resource. At any time, a thread can be terminated, which halts its execution immediately. Once terminated, a thread cannot be resumed.

# Thread Priorities

Java assigns to each thread a priority that determines how that thread should be treated with respect to the others. Thread priorities are integers that specify the relative priority of one thread to another. As an absolute value, a priority is meaningless; a higher-priority thread doesn’t run any faster than a lower-priority thread if it is the only thread running. Instead, a thread’s priority is used to decide when to switch from one running thread to the next. This is called a context switch. The rules that determine when a context switch takes place are simple:

• A thread can voluntarily relinquish control. This occurs when explicitly yielding, sleeping, or when blocked. In this scenario, all other threads are examined, and the highest-priority thread that is ready to run is given the CPU.

• A thread can be preempted by a higher-priority thread. In this case, a lower-priority thread that does not yield the processor is simply preempted—no matter what it is doing—by a higher-priority thread. Basically, as soon as a higher-priority thread wants to run, it does. This is called preemptive multitasking.

In cases where two threads with the same priority are competing for CPU cycles, the situation is a bit complicated. For some operating systems, threads of equal priority are time-sliced automatically in round-robin fashion. For other types of operating systems, threads of equal priority must voluntarily yield control to their peers. If they don’t, the other threads will not run.

CAUTION Portability problems can arise from the differences in the way that operating systems context-switch threads of equal priority.

# Synchronization

Because multithreading introduces an asynchronous behavior to your programs, there must be a way for you to enforce synchronicity when you need it. For example, if you want two threads to communicate and share a complicated data structure, such as a linked list, you need some way to ensure that they don’t conflict with each other. That is, you must prevent one thread from writing data while another thread is in the middle of reading it. For this purpose, Java implements an elegant twist on an age-old model of interprocess synchronization: the monitor. The monitor is a control mechanism first defined by C.A.R. Hoare. You can think of a monitor as a very small box that can hold only one thread. Once a thread enters a monitor, all other threads must wait until that thread exits the monitor. In this way, a monitor can be used to protect a shared asset from being manipulated by more than one thread at a time.

In Java, there is no class “Monitor”; instead, each object has its own implicit monitor that is automatically entered when one of the object’s synchronized methods is called. Once a thread is inside a synchronized method, no other thread can call any other synchronized method on the same object. This enables you to write very clear and concise multithreaded code, because synchronization support is built into the language.

# Messaging

After you divide your program into separate threads, you need to define how they will communicate with each other. When programming with some other languages, you must depend on the operating system to establish communication between threads. This, of course, adds overhead. By contrast, Java provides a clean, low-cost way for two or more threads to talk to each other, via calls to predefined methods that all objects have. Java’s messaging system allows a thread to enter a synchronized method on an object, and then wait there until some other thread explicitly notifies it to come out.

# The Thread Class and the Runnable Interface

Java’s multithreading system is built upon the Thread class, its methods, and its companion interface, Runnable. Thread encapsulates a thread of execution. Since you can’t directly refer to the ethereal state of a running thread, you will deal with it through its proxy, the Thread instance that spawned it. To create a new thread, your program will either extend Thread or implement the Runnable interface.

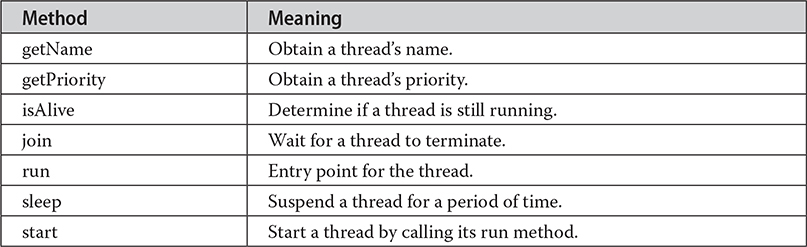

The Thread class defines several methods that help manage threads. Several of those used in this chapter are shown here:

Thus far, all the examples in this book have used a single thread of execution. The remainder of this chapter explains how to use Thread and Runnable to create and manage threads, beginning with the one thread that all Java programs have: the main thread.

# The Main Thread

When a Java program starts up, one thread begins running immediately. This is usually called the main thread of your program, because it is the one that is executed when your program begins. The main thread is important for two reasons:

• It is the thread from which other “child” threads will be spawned.

• Often, it must be the last thread to finish execution because it performs various shutdown actions.

Although the main thread is created automatically when your program is started, it can be controlled through a Thread object. To do so, you must obtain a reference to it by calling the method currentThread( ), which is a public static member of Thread. Its general form is shown here:

static Thread currentThread( )

This method returns a reference to the thread in which it is called. Once you have a reference to the main thread, you can control it just like any other thread.

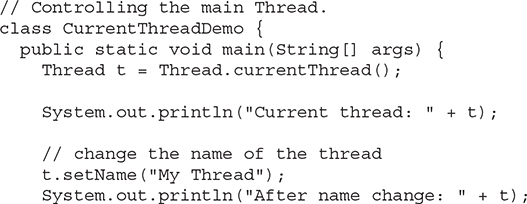

Let’s begin by reviewing the following example:

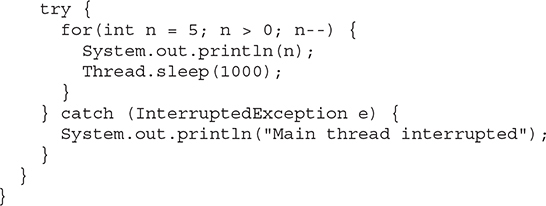

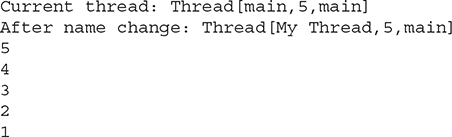

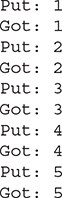

In this program, a reference to the current thread (the main thread, in this case) is obtained by calling currentThread( ), and this reference is stored in the local variable t. Next, the program displays information about the thread. The program then calls setName( ) to change the internal name of the thread. Information about the thread is then redisplayed. Next, a loop counts down from five, pausing one second between each line. The pause is accomplished by the sleep( ) method. The argument to sleep( ) specifies the delay period in milliseconds. Notice the try/catch block around this loop. The sleep( ) method in Thread might throw an InterruptedException. This would happen if some other thread wanted to interrupt this sleeping one. This example just prints a message if it gets interrupted. In a real program, you would need to handle this differently. Here is the output generated by this program:

Notice the output produced when t is used as an argument to println( ). This displays, in order: the name of the thread, its priority, and the name of its group. By default, the name of the main thread is main. Its priority is 5, which is the default value, and main is also the name of the group of threads to which this thread belongs. A thread group is a data structure that controls the state of a collection of threads as a whole. After the name of the thread is changed, t is again output. This time, the new name of the thread is displayed.

Let’s look more closely at the methods defined by Thread that are used in the program. The sleep( ) method causes the thread from which it is called to suspend execution for the specified period of milliseconds. Its general form is shown here:

static void sleep(long milliseconds) throws InterruptedException

The number of milliseconds to suspend is specified in milliseconds. This method may throw an InterruptedException.

The sleep( ) method has a second form, shown next, that allows you to specify the period in terms of milliseconds and nanoseconds:

static void sleep(long milliseconds, int nanoseconds) throws InterruptedException

This second form is useful only in environments that allow timing periods as short as nanoseconds.

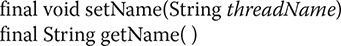

As the preceding program shows, you can set the name of a thread by using setName( ). You can obtain the name of a thread by calling getName( ) (but note that this is not shown in the program). These methods are members of the Thread class and are declared like this:

Here, threadName specifies the name of the thread.

# Creating a Thread

In the most general sense, you create a thread by instantiating an object of type Thread. Java defines two ways in which this can be accomplished:

• You can implement the Runnable interface.

• You can extend the Thread class itself.

The following two sections look at each method, in turn.

# Implementing Runnable

The easiest way to create a thread is to create a class that implements the Runnable interface. Runnable abstracts a unit of executable code. You can construct a thread on any object that implements Runnable. To implement Runnable, a class need only implement a single method called run( ), which is declared like this:

public void run( )

Inside run( ), you will define the code that constitutes the new thread. It is important to understand that run( ) can call other methods, use other classes, and declare variables, just like the main thread can. The only difference is that run( ) establishes the entry point for another, concurrent thread of execution within your program. This thread will end when run( ) returns.

After you create a class that implements Runnable, you will instantiate an object of type Thread from within that class. Thread defines several constructors. The one that we will use is shown here:

Thread(Runnable threadOb, String threadName)

In this constructor, threadOb is an instance of a class that implements the Runnable interface. This defines where execution of the thread will begin. The name of the new thread is specified by threadName.

After the new thread is created, it will not start running until you call its start( ) method, which is declared within Thread. In essence, start( ) initiates a call to run( ). The start( ) method is shown here:

void start( )

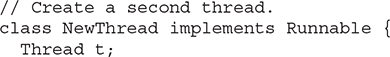

Here is an example that creates a new thread and starts it running:

Inside NewThread’s constructor, a new Thread object is created by the following statement:

t = new Thread(this, "Demo Thread");

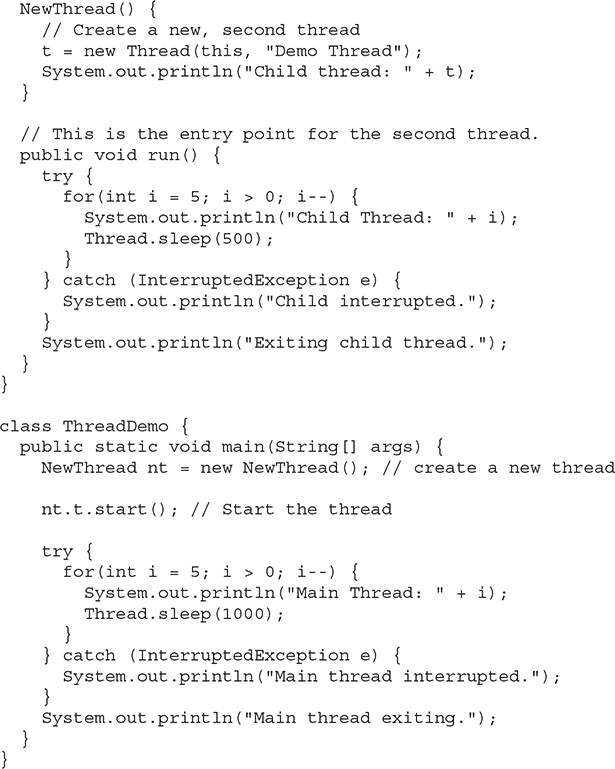

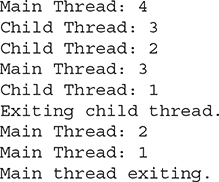

Passing this as the first argument indicates that you want the new thread to call the run( ) method on the this object. Inside main( ), start( ) is called, which starts the thread of execution beginning at the run( ) method. This causes the child thread’s for loop to begin. Next, the main thread enters its for loop. Both threads continue running, sharing the CPU in single-core systems, until their loops finish. The output produced by this program is as follows.(Your output may vary based upon the specific execution environment.)

As mentioned earlier, in a multithreaded program, it is often useful for the main thread to be the last thread to finish running. The preceding program ensures that the main thread finishes last, because the main thread sleeps for 1000 milliseconds between iterations, but the child thread sleeps for only 500 milliseconds. This causes the child thread to terminate earlier than the main thread. Shortly, you will see a better way to wait for a thread to finish.

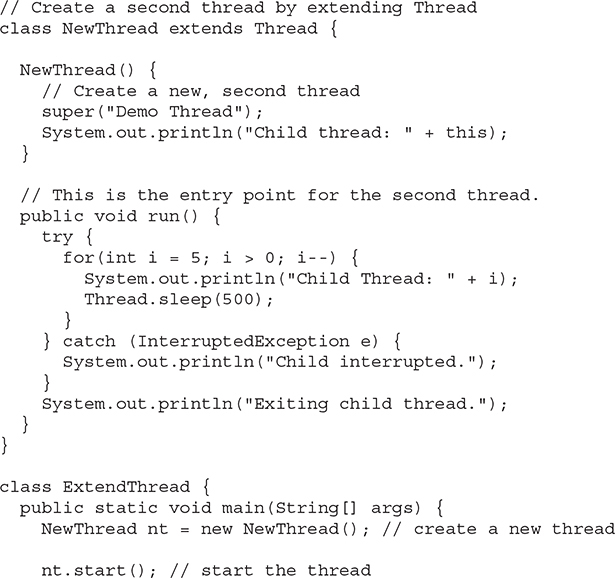

# Extending Thread

The second way to create a thread is to create a new class that extends Thread, and then to create an instance of that class. The extending class must override the run( ) method, which is the entry point for the new thread. As before, a call to start( ) begins execution of the new thread. Here is the preceding program rewritten to extend Thread:

This program generates the same output as the preceding version. As you can see, the child thread is created by instantiating an object of NewThread, which is derived from Thread.

Notice the call to super( ) inside NewThread. This invokes the following form of the Thread constructor:

public Thread(String threadName)

Here, threadName specifies the name of the thread.

# Choosing an Approach

At this point, you might be wondering why Java has two ways to create child threads, and which approach is better. The answers to these questions turn on the same point. The Thread class defines several methods that can be overridden by a derived class. Of these methods, the only one that must be overridden is run( ). This is, of course, the same method required when you implement Runnable. Many Java programmers feel that classes should be extended only when they are being enhanced or adapted in some way. So, if you will not be overriding any of Thread’s other methods, it is probably best simply to implement Runnable. Also, by implementing Runnable, your thread class does not need to inherit Thread, making it free to inherit a different class. Ultimately, which approach to use is up to you. However, throughout the rest of this chapter, we will create threads by using classes that implement Runnable.

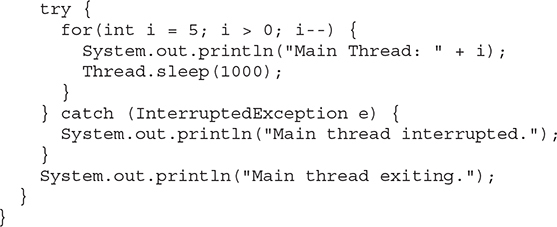

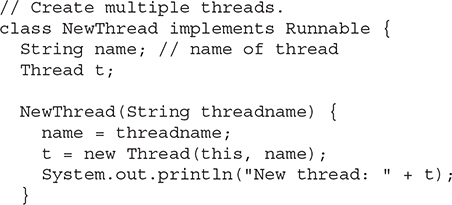

# Creating Multiple Threads

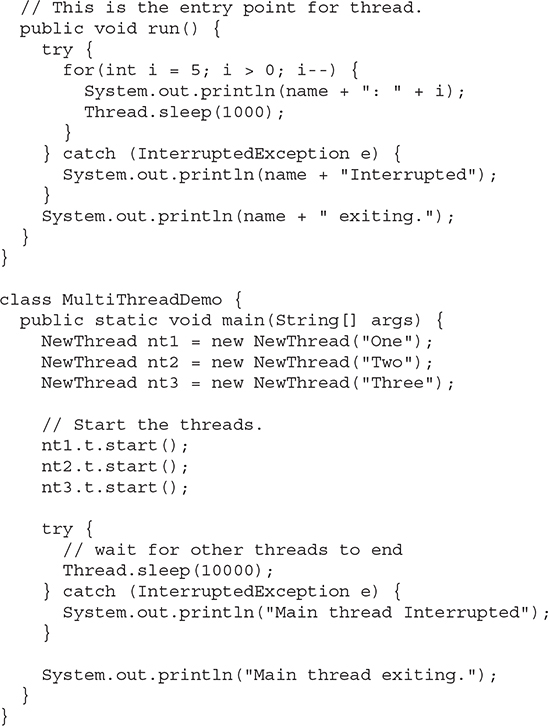

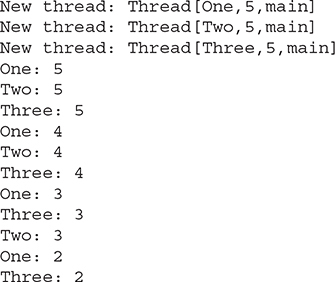

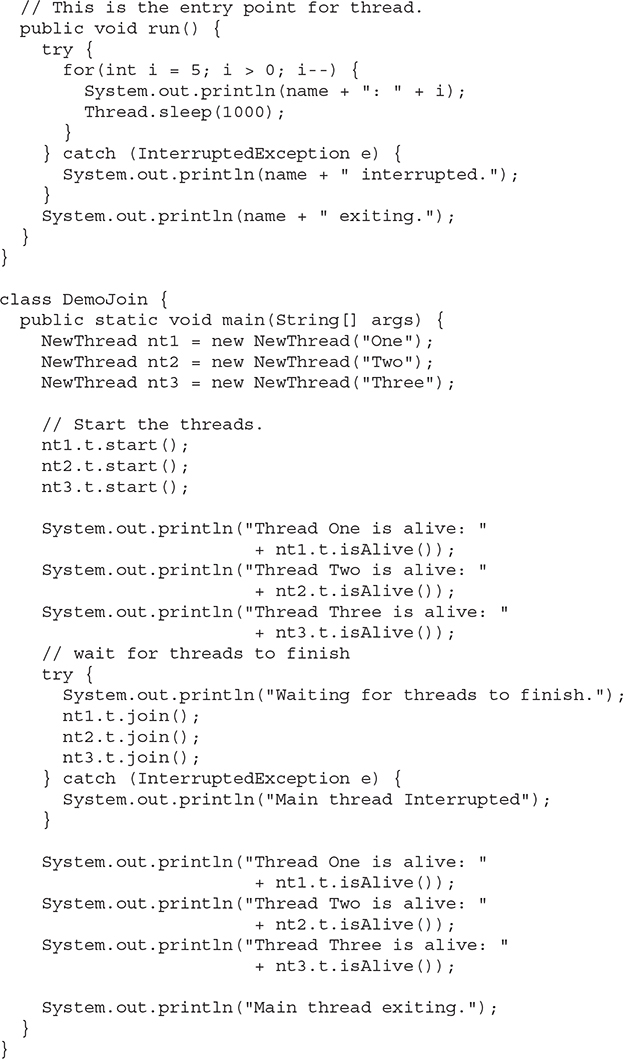

So far, you have been using only two threads: the main thread and one child thread. However, your program can spawn as many threads as it needs. For example, the following program creates three child threads:

Sample output from this program is shown here. (Your output may vary based upon the specific execution environment.)

As you can see, once started, all three child threads share the CPU. Notice the call to sleep(10000) in main( ). This causes the main thread to sleep for ten seconds and ensures that it will finish last.

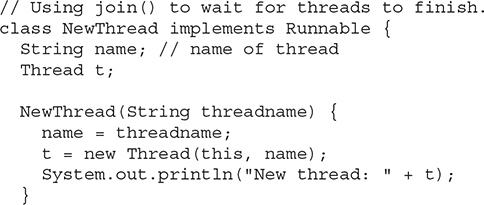

# Using isAlive( ) and join( )

As mentioned, often you will want the main thread to finish last. In the preceding examples, this is accomplished by calling sleep( ) within main( ), with a long enough delay to ensure that all child threads terminate prior to the main thread. However, this is hardly a satisfactory solution, and it also raises a larger question: How can one thread know when another thread has ended? Fortunately, Thread provides a means by which you can answer this question.

Two ways exist to determine whether a thread has finished. First, you can call isAlive( ) on the thread. This method is defined by Thread, and its general form is shown here:

final boolean isAlive( )

The isAlive( ) method returns true if the thread upon which it is called is still running. It returns false otherwise.

While isAlive( ) is occasionally useful, the method that you will more commonly use to wait for a thread to finish is called join( ), shown here:

final void join( ) throws InterruptedException

This method waits until the thread on which it is called terminates. Its name comes from the concept of the calling thread waiting until the specified thread joins it. Additional forms of join( ) allow you to specify a maximum amount of time that you want to wait for the specified thread to terminate.

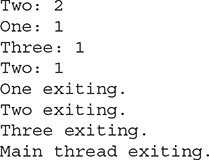

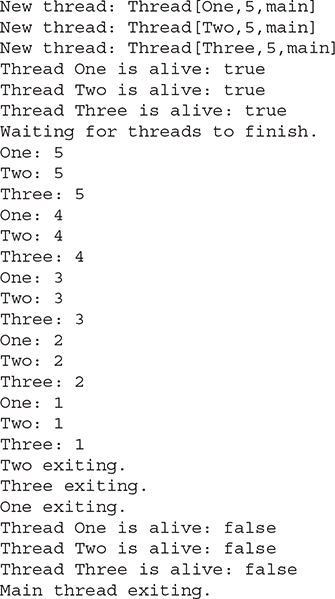

Here is an improved version of the preceding example that uses join( ) to ensure that the main thread is the last to finish. It also demonstrates the isAlive( ) method.

Sample output from this program is shown here. (Your output may vary based upon the specific execution environment.)

As you can see, after the calls to join( ) return, the threads have stopped executing.

# Thread Priorities

Thread priorities are used by the thread scheduler to decide when each thread should be allowed to run. In theory, over a given period of time, higher-priority threads get more CPU time than lower-priority threads. In practice, the amount of CPU time that a thread gets often depends on several factors besides its priority. (For example, how an operating system implements multitasking can affect the relative availability of CPU time.) A higher-priority thread can also preempt a lower-priority one. For instance, when a lower-priority thread is running and a higher-priority thread resumes (from sleeping or waiting on I/O, for example), it will preempt the lower-priority thread.

In theory, threads of equal priority should get equal access to the CPU. But you need to be careful. Remember, Java is designed to work in a wide range of environments. Some of those environments implement multitasking fundamentally differently than others. You should think of the thread priority as a polite suggestion to the thread scheduler as to how to prioritize your threads at times when the system resources are getting stretched. But the thread scheduler will likely have other factors to consider as well. So you should experiment with your application in a range of conditions if you are using thread priorities and not depend on it as if it were a strict rule.

To set a thread’s priority, use the setPriority( ) method, which is a member of Thread. This is its general form:

final void setPriority(int level)

Here, level specifies the new priority setting for the calling thread. The value of level must be within the range MIN_PRIORITY and MAX_PRIORITY. Currently, these values are 1 and 10, respectively. To return a thread to default priority, specify NORM_PRIORITY, which is currently 5. These priorities are defined as static final variables within Thread.

You can obtain the current priority setting by calling the getPriority( ) method of Thread, shown here:

final int getPriority( )

Implementations of Java may have radically different behavior when it comes to scheduling. Most of the inconsistencies arise when you have threads that are relying on preemptive behavior, instead of cooperatively giving up CPU time. The safest way to obtain predictable, cross-platform behavior with Java is to use threads that voluntarily give up control of the CPU.

# Synchronization

When two or more threads need access to a shared resource, they need some way to ensure that the resource will be used by only one thread at a time. The process by which this is achieved is called synchronization. As you will see, Java provides unique, language-level support for it.

Key to synchronization is the concept of the monitor. A monitor is an object that is used as a mutually exclusive lock. Only one thread can own a monitor at a given time. When a thread acquires a lock, it is said to have entered the monitor. All other threads attempting to enter the locked monitor will be suspended until the first thread exits the monitor. These other threads are said to be waiting for the monitor. A thread that owns a monitor can reenter the same monitor if it so desires.

You can synchronize your code in either of two ways. Both involve the use of the synchronized keyword, and both are examined here.

# Using Synchronized Methods

Synchronization is easy in Java, because all objects have their own implicit monitor associated with them. To enter an object’s monitor, just call a method that has been modified with the synchronized keyword. While a thread is inside a synchronized method, all other threads that try to call it (or any other synchronized method) on the same instance have to wait. To exit the monitor and relinquish control of the object to the next waiting thread, the owner of the monitor simply returns from the synchronized method.

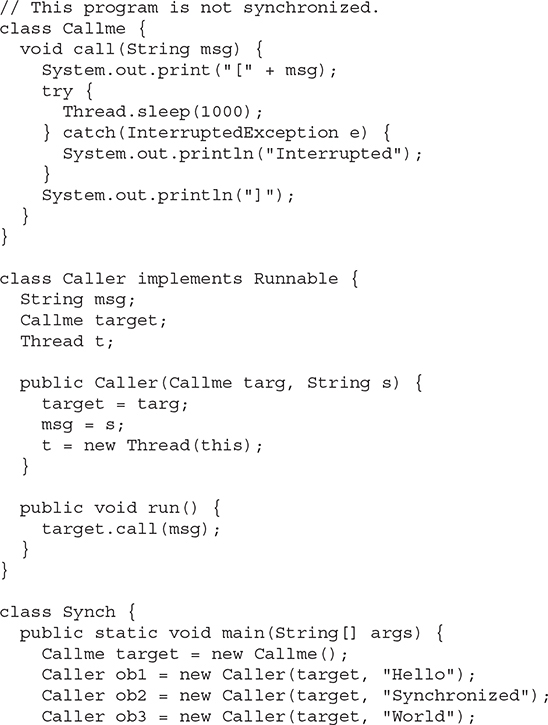

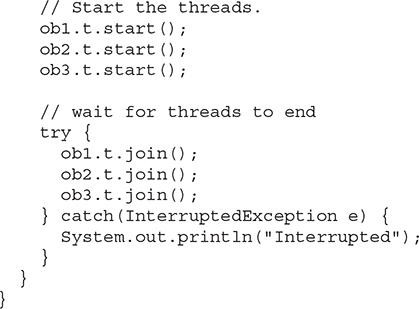

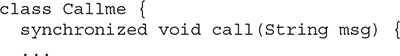

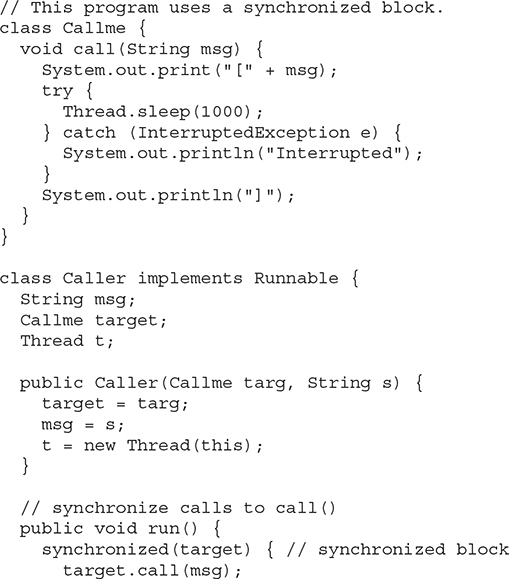

To understand the need for synchronization, let’s begin with a simple example that does not use it—but should. The following program has three simple classes. The first one, Callme, has a single method named call( ). The call( ) method takes a String parameter called msg. This method tries to print the msg string inside of square brackets. The interesting thing to notice is that after call( ) prints the opening bracket and the msg string, it calls Thread.sleep(1000), which pauses the current thread for one second.

The constructor of the next class, Caller, takes a reference to an instance of the Callme class and a String, which are stored in target and msg, respectively. The constructor also creates a new thread that will call this object’s run( ) method. The run( ) method of Caller calls the call( ) method on the target instance of Callme, passing in the msg string. Finally, the Synch class starts by creating a single instance of Callme, and three instances of Caller, each with a unique message string. The same instance of Callme is passed to each Caller.

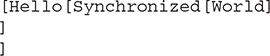

Here is the output produced by this program:

As you can see, by calling sleep( ), the call( ) method allows execution to switch to another thread. This results in the mixed-up output of the three message strings. In this program, nothing exists to prevent all three threads from calling the same method, on the same object, at the same time. This is known as a race condition, because the three threads are racing each other to complete the method. This example used sleep( ) to make the effects repeatable and obvious. In most situations, a race condition is more subtle and less predictable, because you can’t be sure when the context switch will occur. This can cause a program to run right one time and wrong the next.

To fix the preceding program, you must serialize access to call( ). That is, you must restrict its access to only one thread at a time. To do this, you simply need to precede call( )’s definition with the keyword synchronized, as shown here:

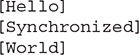

This prevents other threads from entering call( ) while another thread is using it. After synchronized has been added to call( ), the output of the program is as follows:

Any time that you have a method, or group of methods, that changes the internal state of an object in a multithreaded situation, you should consider using the synchronized keyword to guard the state from race conditions. Remember, once a thread enters any synchronized method on an instance, no other thread can enter any other synchronized method on the same instance. However, nonsynchronized methods on that instance will continue to be callable.

# The synchronized Statement

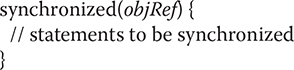

While creating synchronized methods within classes that you create is an easy and effective means of achieving synchronization, it will not work in all cases. To understand why, consider the following: Imagine that you want to synchronize access to objects of a class that was not designed for multithreaded access. That is, the class does not use synchronized methods. Further, this class was not created by you, but by a third party, and you do not have access to the source code. Thus, you can’t add synchronized to the appropriate methods within the class. How can access to an object of this class be synchronized? Fortunately, the solution to this problem is quite easy: You simply put calls to the methods defined by this class inside a synchronized block.

This is the general form of the synchronized statement:

Here, objRef is a reference to the object being synchronized. A synchronized block ensures that a call to a synchronized method that is a member of objRef’s class occurs only after the current thread has successfully entered objRef’s monitor.

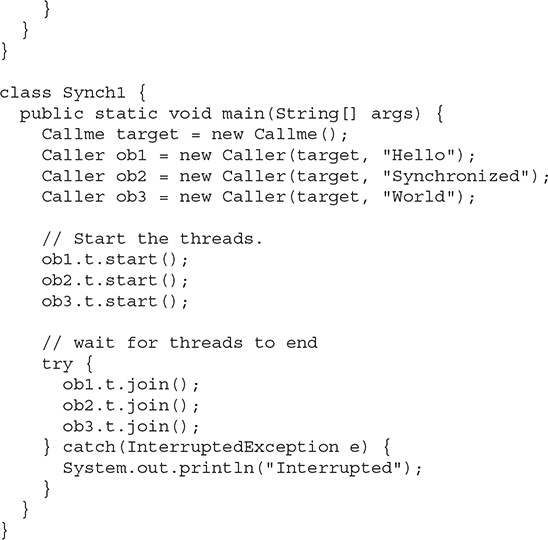

Here is an alternative version of the preceding example, using a synchronized block within the run( ) method:

Here, the call( ) method is not modified by synchronized. Instead, the synchronized statement is used inside Caller’s run( ) method. This causes the same correct output as the preceding example, because each thread waits for the prior one to finish before proceeding.

# Interthread Communication

The preceding examples unconditionally blocked other threads from asynchronous access to certain methods. This use of the implicit monitors in Java objects is powerful, but you can achieve a more subtle level of control through interthread communication. As you will see, this is especially easy in Java.

As discussed earlier, multithreading replaces event loop programming by dividing your tasks into discrete, logical units. Threads also provide a secondary benefit: they do away with polling. Polling is usually implemented by a loop that is used to check some condition repeatedly. Once the condition is true, appropriate action is taken. This wastes CPU time. For example, consider the classic queuing problem, where one thread is producing some data and another is consuming it. To make the problem more interesting, suppose that the producer has to wait until the consumer is finished before it generates more data. In a polling system, the consumer would waste many CPU cycles while it waited for the producer to produce. Once the producer was finished, it would start polling, wasting more CPU cycles waiting for the consumer to finish, and so on. Clearly, this situation is undesirable.

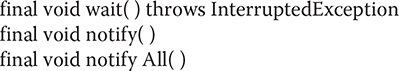

To avoid polling, Java includes an elegant interthread communication mechanism via the wait( ), notify( ), and notifyAll( ) methods. These methods are implemented as final methods in Object, so all classes have them. All three methods can be called only from within a synchronized context. Although conceptually advanced from a computer science perspective, the rules for using these methods are actually quite simple:

• wait( ) tells the calling thread to give up the monitor and go to sleep until some other thread enters the same monitor and calls notify( ) or notifyAll( ).

• notify( ) wakes up a thread that called wait( ) on the same object.

• notifyAll( ) wakes up all the threads that called wait( ) on the same object. One of the threads will be granted access.

These methods are declared within Object, as shown here:

Additional forms of wait( ) exist that allow you to specify a period of time to wait.

Before working through an example that illustrates interthread communication, an important point needs to be made. Although wait( ) normally waits until notify( ) or notifyAll( ) is called, there is a possibility that in very rare cases the waiting thread could be awakened due to a spurious wakeup. In this case, a waiting thread resumes without notify( ) or notifyAll( ) having been called. (In essence, the thread resumes for no apparent reason.) Because of this remote possibility, the Java API documentation recommends that calls to wait( ) should take place within a loop that checks the condition on which the thread is waiting. The following example shows this technique.

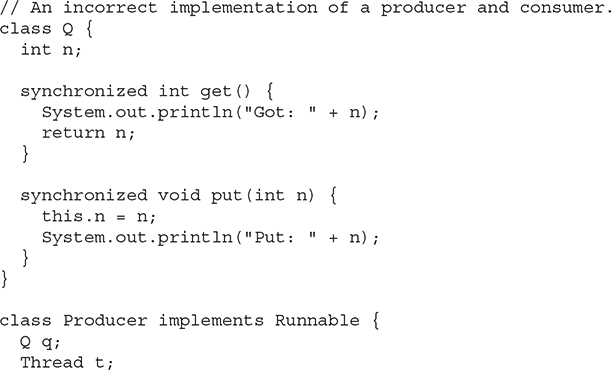

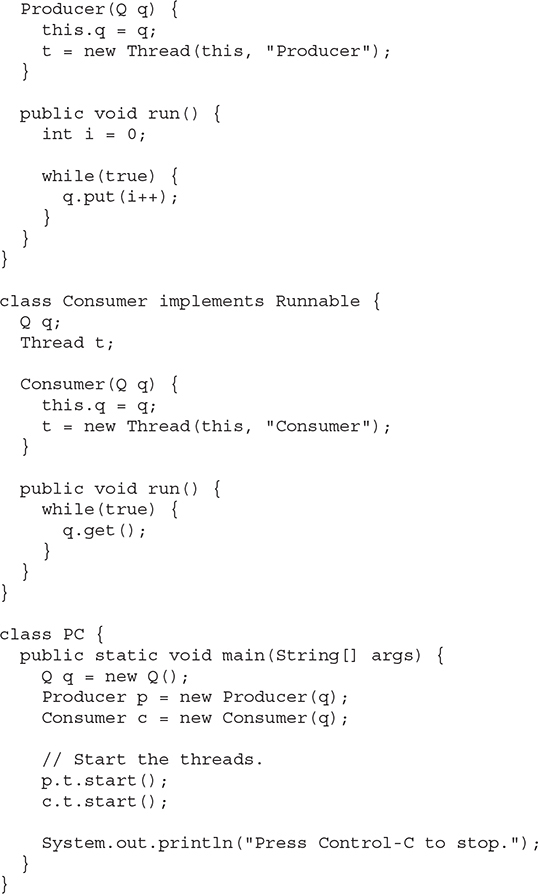

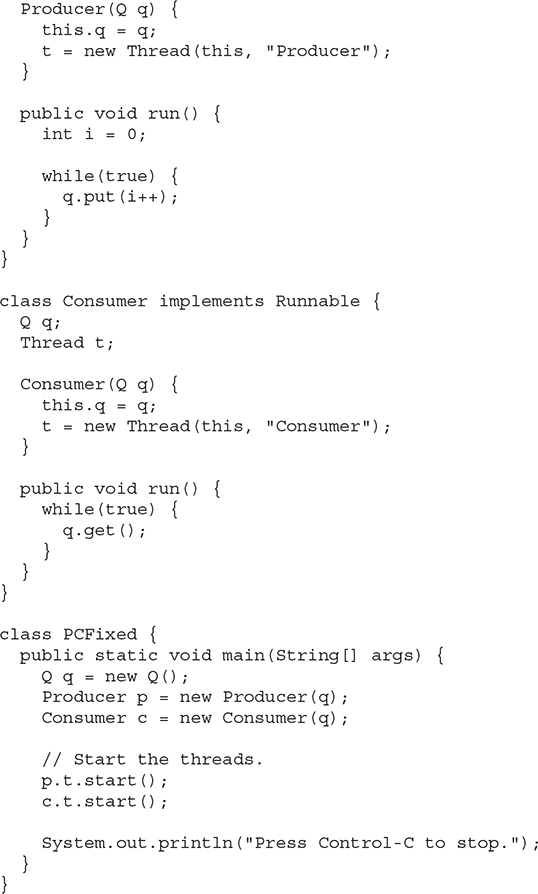

Let’s now work through an example that uses wait( ) and notify( ). To begin, consider the following sample program that incorrectly implements a simple form of the producer/consumer problem. It consists of four classes: Q, the queue that you’re trying to synchronize; Producer, the threaded object that is producing queue entries; Consumer, the threaded object that is consuming queue entries; and PC, the tiny class that creates the single Q, Producer, and Consumer.

Although the put( ) and get( ) methods on Q are synchronized, nothing stops the producer from overrunning the consumer, nor will anything prevent the consumer from consuming the same queue value twice. Thus, you get the erroneous output shown here (the exact output will vary with processor speed and task load):

As you can see, after the producer put 1, the consumer started and got the same 1 five times in a row. Then, the producer resumed and produced 2 through 7 without letting the consumer have a chance to consume them.

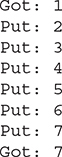

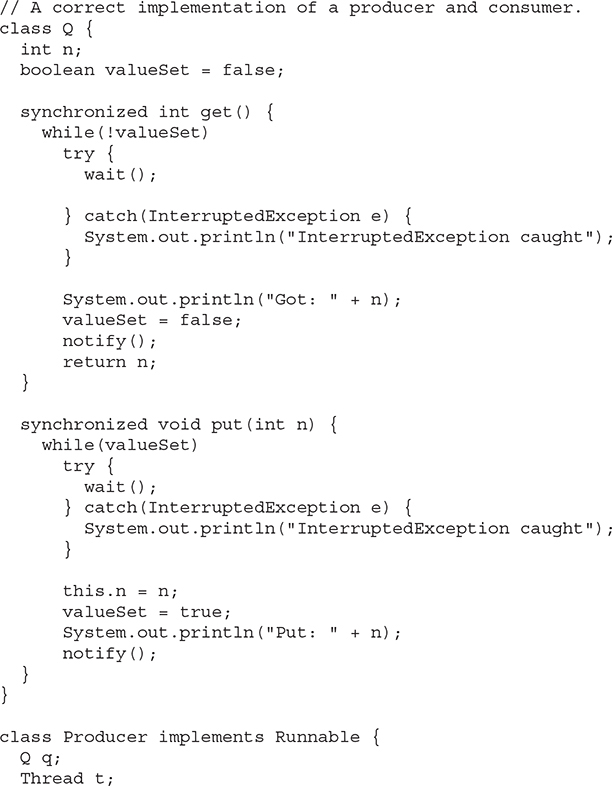

The proper way to write this program in Java is to use wait( ) and notify( ) to signal in both directions, as shown here:

Inside get( ), wait( ) is called. This causes its execution to suspend until Producer notifies you that some data is ready. When this happens, execution inside get( ) resumes. After the data has been obtained, get( ) calls notify( ). This tells Producer that it is okay to put more data in the queue. Inside put( ), wait( ) suspends execution until Consumer has removed the item from the queue. When execution resumes, the next item of data is put in the queue, and notify( ) is called. This tells Consumer that it should now remove it.

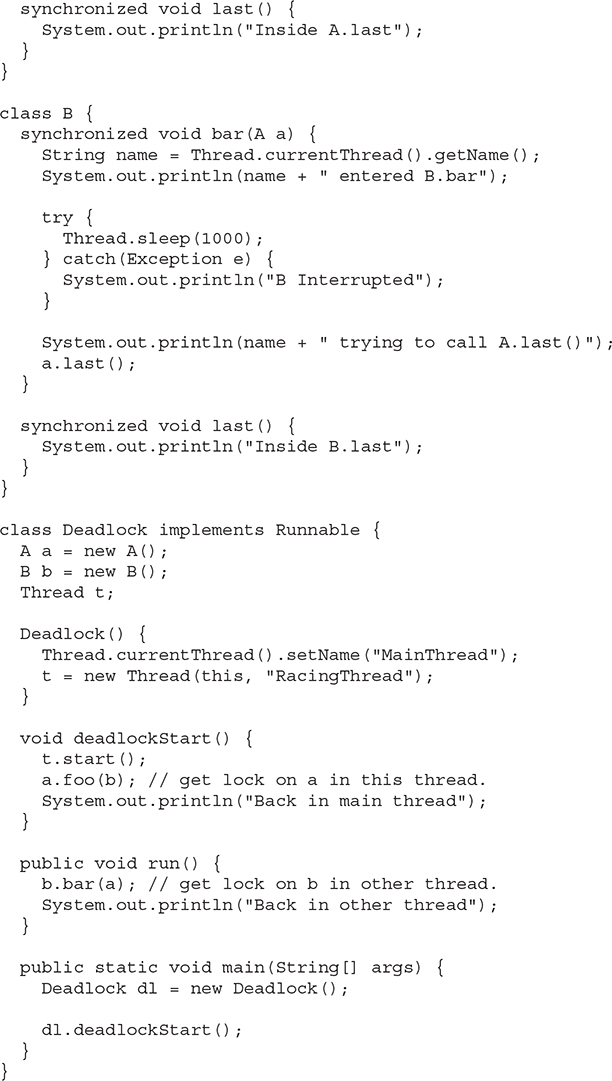

Here is some output from this program, which shows the clean synchronous behavior:

# Deadlock

A special type of error that you need to avoid that relates specifically to multitasking is deadlock, which occurs when two threads have a circular dependency on a pair of synchronized objects. For example, suppose one thread enters the monitor on object X and another thread enters the monitor on object Y. If the thread in X tries to call any synchronized method on Y, it will block as expected. However, if the thread in Y, in turn, tries to call any synchronized method on X, the thread waits forever, because to access X, it would have to release its own lock on Y so that the first thread could complete. Deadlock is a difficult error to debug for two reasons:

• In general, it occurs unpredictably, when the two threads time-slice in just the right way.

• It may involve more than two threads and two synchronized objects. (That is, deadlock can occur through a more convoluted sequence of events than just described.)

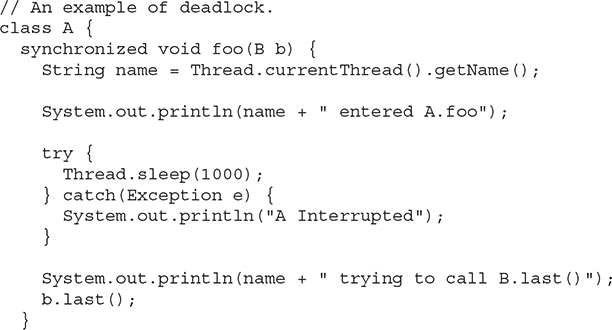

To understand deadlock fully, it is useful to see it in action. The next example creates two classes, A and B, with methods foo( ) and bar( ), respectively, which pause briefly before trying to call a method in the other class. The main class, named Deadlock, creates an A and a B instance, and then calls deadlockStart( ) to start a second thread that sets up the deadlock condition. The foo( ) and bar( ) methods use sleep( ) as a way to force the deadlock condition to occur.

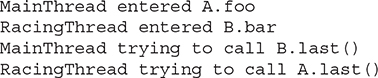

When you run this program, you will see the output shown here, although whether A.foo( ) or B.bar( ) executes first will vary based on the specific execution environment.

Because the program has deadlocked, you need to press CTRL-C to end the program. You can see a full thread and monitor cache dump by pressing CTRL-BREAK on a PC. You will see that RacingThread owns the monitor on b, while it is waiting for the monitor on a. At the same time, MainThread owns a and is waiting to get b. This program will never complete. As this example illustrates, if your multithreaded program locks up occasionally, deadlock is one of the first conditions that you should check for.

# Suspending, Resuming, and Stopping Threads

Sometimes, suspending execution of a thread is useful. For example, a separate thread can be used to display the time of day. If the user doesn’t want a clock, then its thread can be suspended. Whatever the case, suspending a thread is a simple matter. Once it’s suspended, restarting the thread is also a simple matter.

The mechanisms to suspend, stop, and resume threads differ between early versions of Java, such as Java 1.0, and more modern versions, beginning with Java 2. Prior to Java 2, a program used suspend( ), resume( ), and stop( ), which are methods defined by Thread, to pause, restart, and stop the execution of a thread, respectively. Although these methods seem to be a perfectly reasonable and convenient approach to managing the execution of threads, they must not be used for new Java programs. Here’s why. The suspend( ) method of the Thread class was deprecated by Java 2 several years ago, and will be removed in a future release. This was done because suspend( ) can sometimes cause serious system failures. Assume that a thread has obtained locks on critical data structures. If that thread is suspended at that point, those locks are not relinquished. Other threads that may be waiting for those resources can be deadlocked.

The resume( ) method is also deprecated. It does not cause problems, but it cannot be used without the suspend( ) method as its counterpart.

The stop( ) method of the Thread class, too, was deprecated by Java 2, and will be removed in a future release. This was done because this method can sometimes cause serious system failures. Assume that a thread is writing to a critically important data structure and has completed only part of its changes. If that thread is stopped at that point, that data structure might be left in a corrupted state. The trouble is that stop( ) causes any lock the calling thread holds to be released. Thus, the corrupted data might be used by another thread that is waiting on the same lock.

Because you can’t now use the suspend( ), resume( ), or stop( ) methods to control a thread, you might be thinking that no way exists to pause, restart, or terminate a thread. But, fortunately, this is not true. Instead, a thread must be designed so that the run( ) method periodically checks to determine whether that thread should suspend, resume, or stop its own execution. Typically, this is accomplished by establishing a flag variable that indicates the execution state of the thread. As long as this flag is set to “running,” the run( ) method must continue to let the thread execute. If this variable is set to “suspend,” the thread must pause. If it is set to “stop,” the thread must terminate. Of course, a variety of ways exist in which to write such code, but the central theme will be the same for all programs.

The following example illustrates how the wait( ) and notify( ) methods that are inherited from Object can be used to control the execution of a thread. Let us consider its operation. The NewThread class contains a boolean instance variable named suspendFlag, which is used to control the execution of the thread. It is initialized to false by the constructor. The run( ) method contains a synchronized statement block that checks suspendFlag. If that variable is true, the wait( ) method is invoked to suspend the execution of the thread. The mysuspend( ) method sets suspendFlag to true. The myresume( ) method sets suspendFlag to false and invokes notify( ) to wake up the thread. Finally, the main( ) method has been modified to invoke the mysuspend( ) and myresume( ) methods.

When you run the program, you will see the threads suspend and resume. Later in this book, you will see more examples that use the modern mechanism of thread control. Although this mechanism may not appear as simple to use as the old way, nevertheless, it is the way required to ensure that run-time errors don’t occur. It is the approach that must be used for all new code.

# Obtaining a Thread’s State

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, a thread can exist in a number of different states. You can obtain the current state of a thread by calling the getState( ) method defined by Thread. It is shown here:

Thread.State getState( )

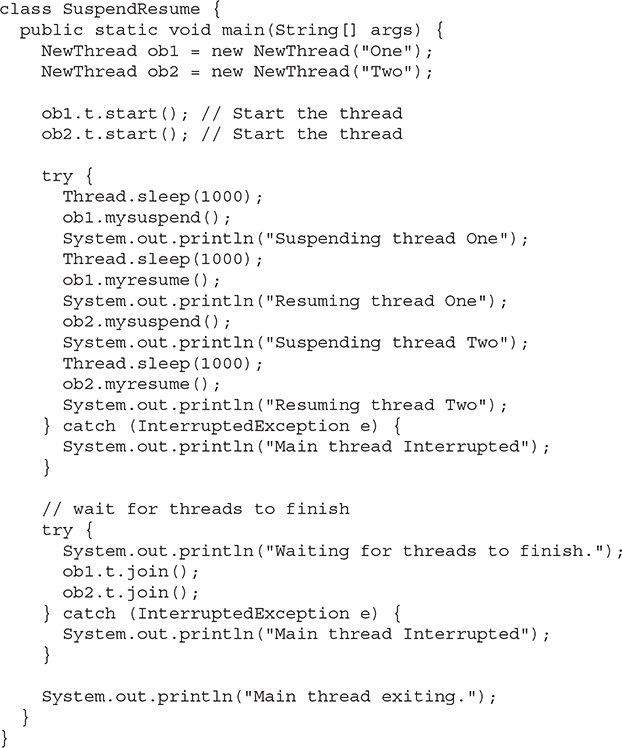

It returns a value of type Thread.State that indicates the state of the thread at the time at which the call was made. State is an enumeration defined by Thread. (An enumeration is a list of named constants. It is discussed in detail in Chapter 12.) Here are the values that can be returned by getState( ):

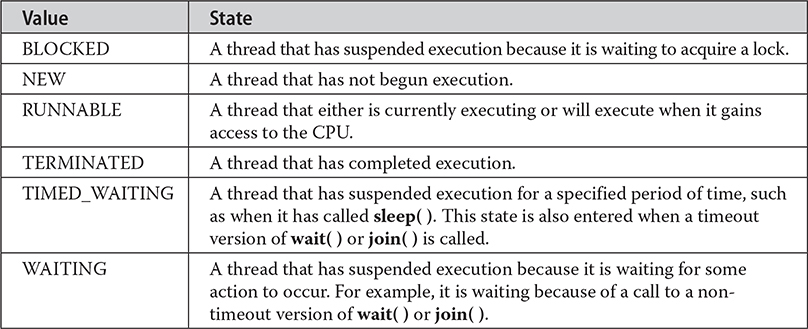

Figure 11-1 diagrams how the various thread states relate.

Figure 11-1 Thread states

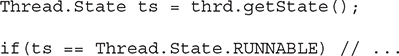

Given a Thread instance, you can use getState( ) to obtain the state of a thread. For example, the following sequence determines if a thread called thrd is in the RUNNABLE state at the time getState( ) is called:

It is important to understand that a thread’s state may change after the call to getState( ). Thus, depending on the circumstances, the state obtained by calling getState( ) may not reflect the actual state of the thread only a moment later. For this (and other) reasons, getState( ) is not intended to provide a means of synchronizing threads. It’s primarily used for debugging or for profiling a thread’s run-time characteristics.

# Using a Factory Method to Create and Start a Thread

In some cases, it is not necessary to separate the creation of a thread from the start of its execution. In other words, sometimes it is convenient to create and start a thread at the same time. One way to do this is to use a static factory method. A factory method is a method that returns an object of a class. Typically, factory methods are static methods of a class. They are used for a variety of reasons, such as to set an object to some initial state prior to use, to configure a specific type of object, or in some cases to enable an object to be reused. As it relates to creating and starting a thread, a factory method will create the thread, call start( ) on the thread, and then return a reference to the thread. With this approach, you can create and start a thread through a single method call, thus streamlining your code.

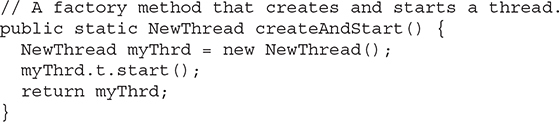

For example, assuming the ThreadDemo program shown near the start of this chapter, adding the following factory method to NewThread enables you to create and start a thread in a single step:

Using createAndStart( ), you can now replace the sequence

with

NewThread nt = NewThread.createAndStart();

Now the thread is created and started in one step.

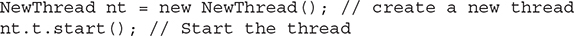

In cases in which you don’t need to keep a reference to the executing thread, you can sometimes create and start a thread with one line of code, without the use of a factory method. For example, again assuming the ThreadDemo program, the following creates and starts a NewThread thread:

new NewThread().t.start();

However, in real-world applications, you will usually need to keep a reference to the thread, so the factory method is often a good choice.

# Virtual Threads

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the Java platform implements Java threads as wrappers around the underlying OS’s native threads. In this model, when the OS runs out of threads, so does Java! For high-throughput, high-scale applications such as application servers, which generally like to use a new thread for each new incoming request, this can be a performance bottleneck as to the number of requests the server can handle at the same time. JDK 21 has introduced a new way to map Java threads onto OS threads in which many Java threads can share the same OS thread. This is called virtual threading. By scheduling work on the OS in a more flexible way, high-scale server applications can perform better because they can handle more concurrent requests gracefully. The number of virtual Java threads an application can create is no longer limited to the number of OS threads available to Java.

Fortunately, the programming model for using platform threads and virtual threads is the same except for how the Java threads are first created and managed when the JVM terminates. All the examples so far have created threads that are platform threads, since these are the kind of threads that work well for most applications. You can determine what kind of thread is in use by the Thread class method

boolean isVirtual( )

which is false for platform threads and true for virtual threads.

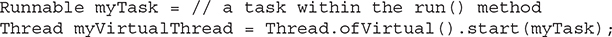

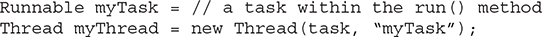

In order to create a virtual thread in Java, you can use the static Thread method ofVirtual( ), from which you can obtain a Thread.Builder object from which to create virtual threads. For example, the code

shows a Runnable task being run on a virtual thread. The virtual thread is an instance of the Java Thread class you already learned about in this chapter, and so it has the same life cycle and API methods for managing execution. It is important to note that if you want to use virtual threads, you have to explicitly choose this API to do so.

The companion to ofVirtual( ) is the static Thread method ofPlatform( ), which creates a Thread.Builder object from which you can create traditional platform threads. However, since platform threads are the default type of threads, the APIs that you have already seen create platform threads, such as

or the default no argument constructor of the Thread class.

While virtual threads “look like” platform threads for the most part, they differ in that they are not named by default (their name variable is the empty string) and the JVM does not wait for them to finish their work when it exits.

If a virtual thread is waiting, the Java platform can schedule its OS thread to be useful for another virtual thread that needs attention. In this way, the Java platform can use OS threads more efficiently for applications that have tasks spending significant time waiting on network connections or blocking I/O. For applications mostly doing continuous processing, like large algorithmic calculations, virtual threads will likely not bring much benefit. So virtual threads, while easy to use because they “look like” traditional threads, bring performance benefits only for certain types of applications and will likely require judicious use together with performance testing to realize their full potential.

# Using Multithreading

The key to utilizing Java’s multithreading features effectively is to think concurrently rather than serially. For example, when you have two subsystems within a program that can execute concurrently, make them individual threads. With the careful use of multithreading, you can create very efficient programs. A word of caution is in order, however: If you create too many threads, you can actually degrade the performance of your program rather than enhance it. Remember, some overhead is associated with context switching. If you create too many threads, more CPU time will be spent changing contexts than executing your program! One last point: To create compute-intensive applications that can automatically scale to make use of the available processors in a multicore system, consider using the Fork/Join Framework, which is described in Chapter 29.