# Operators

Java provides a rich operator environment. Most of its operators can be divided into the following four groups: arithmetic, bitwise, relational, and logical. Java also defines some additional operators that handle certain special situations. This chapter describes all of Java’s operators except for the type comparison operator instanceof, which is examined in Chapter 13, and the arrow operator −>, which is described in Chapter 15.

# Arithmetic Operators

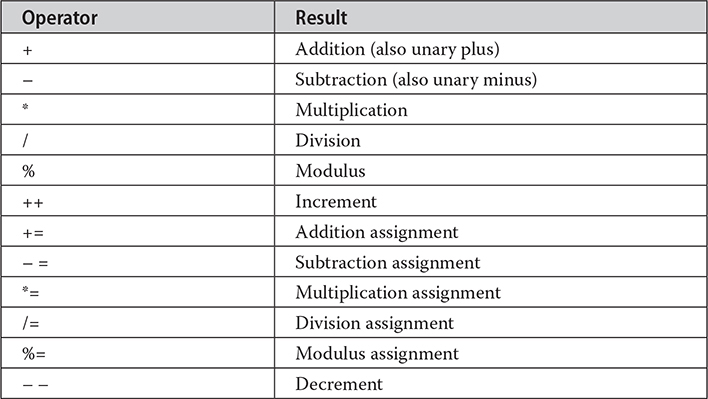

Arithmetic operators are used in mathematical expressions in the same way that they are used in algebra. The following table lists the arithmetic operators:

The operands of the arithmetic operators must be of a numeric type. You cannot use them on boolean types, but you can use them on char types, since the char type in Java is, essentially, a subset of int.

# The Basic Arithmetic Operators

The basic arithmetic operations—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—all behave as you would expect for all numeric types. The unary minus operator negates its single operand. The unary plus operator simply returns the value of its operand. Remember that when the division operator is applied to an integer type, there will be no fractional component attached to the result.

The following simple sample program demonstrates the arithmetic operators. It also illustrates the difference between floating-point division and integer division.

// Demonstrate the basic arithmetic operators.

class BasicMath {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// arithmetic using integers

System.out.println("Integer Arithmetic");

int a = 1 + 1;

int b = a * 3;

int c = b / 4;

int d = c - a;

int e = -d;

System.out.println("a = " + a);

System.out.println("b = " + b);

System.out.println("c = " + c);

System.out.println("d = " + d);

System.out.println("e = " + e);

// arithmetic using doubles

System.out.println("\nFloating Point Arithmetic");

double da = 1 + 1;

double db = da * 3;

double dc = db / 4;

double dd = dc - a;

double de = -dd;

System.out.println("da = " + da);

System.out.println("db = " + db);

System.out.println("dc = " + dc);

System.out.println("dd = " + dd);

System.out.println("de = " + de);

}

}

When you run this program, you will see the following output:

Integer Arithmetic

a = 2

b = 6

c = 1

d = -1

e = 1

Floating Point Arithmetic

da = 2.0

db = 6.0

dc = 1.5

dd = -05

de = 0.5

# The Modulus Operator

The modulus operator, %, returns the remainder of a division operation. It can be applied to floating-point types as well as integer types. The following sample program demonstrates the %:

// Demonstrate the % operator.

class Modulus {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 42;

double y = 42.25;

System.out.println("x mod 10 = " + x % 10);

System.out.println("y mod 10 = " + y % 10);

}

}

When you run this program, you will get the following output:

x mod 10 = 2

y mod 10 = 2.25

# Arithmetic Compound Assignment Operators

Java provides special operators that can be used to combine an arithmetic operation with an assignment. As you probably know, statements like the following are quite common in programming:

a = a + 4;

In Java, you can rewrite this statement as shown here:

a += 4;

This version uses the += compound assignment operator. Both statements perform the same action: they increase the value of a by 4.

Here is another example,

a = a % 2;

which can be expressed as

a %= 2;

In this case, the %= obtains the remainder of a /2 and puts that result back into a.

There are compound assignment operators for all of the arithmetic, binary operators. Thus, any statement of the form

var = var op expression;

can be rewritten as

var op= expression;

The compound assignment operators provide two benefits. First, they save you a bit of typing, because they are “shorthand” for their equivalent long forms. Second, in some cases they are more efficient than are their equivalent long forms. For these reasons, you will often see the compound assignment operators used in professionally written Java programs.

Here is a sample program that shows several op= assignments in action:

// Demonstrate several assignment operators.

class OpEquals {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c = 3;

a += 5;

b *= 4;

c += a * b;

c %= 6;

System.out.println("a = " + a);

System.out.println("b = " + b);

System.out.println("c = " + c);

}

}

The output of this program is shown here:

a = 6

b = 8

c = 3

# Increment and Decrement

The ++ and the – – are Java’s increment and decrement operators, respectively. They were introduced in Chapter 2. Here they will be discussed in detail. As you will see, they have some special properties that make them quite interesting. Let’s begin by reviewing precisely what the increment and decrement operators do.

The increment operator increases its operand by one. The decrement operator decreases its operand by one. For example, this statement:

x = x + 1;

can be rewritten like this by use of the increment operator:

x++;

Similarly, this statement:

x = x - 1;

is equivalent to

x--;

These operators are unique in that they can appear both in postfix form, where they follow the operand as just shown, and prefix form, where they precede the operand. In the foregoing examples, there is no difference between the prefix and postfix forms. However, when the increment and/or decrement operators are part of a larger expression, then a subtle, yet powerful, difference between these two forms appears. In the prefix form, the operand is incremented or decremented before the value is obtained for use in the expression. In postfix form, the previous value is obtained for use in the expression, and then the operand is modified. For example:

x = 42;

y = ++x;

In this case, y is set to 43 as you would expect, because the increment occurs before x is assigned to y. Thus, the line y = ++x; is the equivalent of these two statements:

x = x + 1;

y = x;

However, when written like this,

x = 42;

y = x++;

the value of x is obtained before the increment operator is executed, so the value of y is 42. Of course, in both cases x is set to 43. Here, the line y = x++; is the equivalent of these two statements:

y = x;

x = x + 1;

The following program demonstrates the increment operator:

// Demonstrate ++ and --.

class IncDec {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c;

int d;

c = ++b;

d = a++;

c++;

System.out.println("a = " + a);

System.out.println("b = " + b);

System.out.println("c = " + c);

System.out.println("d = " + d);

}

}

The output of this program follows:

a = 2

b = 3

c = 4

d = 1

# The Bitwise Operators

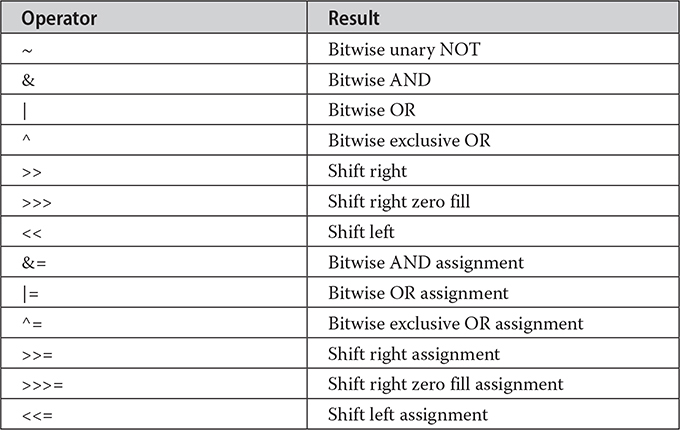

Java defines several bitwise operators that can be applied to the integer types: long, int, short, char, and byte. These operators act upon the individual bits of their operands. They are summarized in the following table:

Since the bitwise operators manipulate the bits within an integer, it is important to understand what effects such manipulations may have on a value. Specifically, it is useful to know how Java stores integer values and how it represents negative numbers. So, before continuing, let’s briefly review these two topics.

All of the integer types are represented by binary numbers of varying bit widths. For example, the byte value for 42 in binary is 00101010, where each position represents a power of two, starting with 20 at the rightmost bit. The next bit position to the left would be 21, or 2, continuing toward the left with 22, or 4, then 8, 16, 32, and so on. So 42 has 1 bits set at positions 1, 3, and 5 (counting from 0 at the right); thus, 42 is the sum of 21 + 23 + 25, which is 2 + 8 + 32.

All of the integer types (except char) are signed integers. This means that they can represent negative values as well as positive ones. Java uses an encoding known as two’s complement, which means that negative numbers are represented by inverting (changing 1’s to 0’s and vice versa) all of the bits in a value, then adding 1 to the result. For example, –42 is represented by inverting all of the bits in 42, or 00101010, which yields 11010101, then adding 1, which results in 11010110, or –42. To decode a negative number, first invert all of the bits, then add 1. For example, –42, or 11010110 inverted, yields 00101001, or 41, so when you add 1 you get 42.

The reason Java (and most other computer languages) uses two’s complement is easy to see when you consider the issue of zero crossing. Assuming a byte value, zero is represented by 00000000. In one’s complement, simply inverting all of the bits creates 11111111, which creates negative zero. The trouble is that negative zero is invalid in integer math. This problem is solved by using two’s complement to represent negative values. When using two’s complement, 1 is added to the complement, producing 100000000. This produces a 1 bit too far to the left to fit back into the byte value, resulting in the desired behavior, where –0 is the same as 0, and 11111111 is the encoding for –1. Although we used a byte value in the preceding example, the same basic principle applies to all of Java’s integer types.

Because Java uses two’s complement to store negative numbers—and because all integers are signed values in Java—applying the bitwise operators can easily produce unexpected results. For example, turning on the high-order bit will cause the resulting value to be interpreted as a negative number, whether this is what you intended or not. To avoid unpleasant surprises, just remember that the high-order bit determines the sign of an integer no matter how that high-order bit gets set.

# The Bitwise Logical Operators

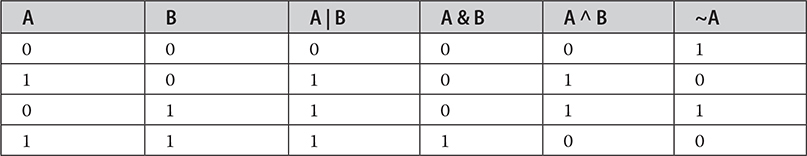

The bitwise logical operators are &, |, ^, and ~. The following table shows the outcome of each operation. In the discussion that follows, keep in mind that the bitwise operators are applied to each individual bit within each operand.

# The Bitwise NOT

Also called the bitwise complement, the unary NOT operator, ~, inverts all of the bits of its operand. For example, the number 42, which has the following bit pattern:

00101010

becomes

11010101

after the NOT operator is applied.

# The Bitwise AND

The AND operator, &, produces a 1 bit if both operands are also 1. A zero is produced in all other cases. Here is an example:

00101010 42

&00001111 15

---------

00001010 10

# The Bitwise OR

The OR operator, |, combines bits such that if either of the bits in the operands is a 1, then the resultant bit is a 1, as shown here:

00101010 42

|00001111 15

---------

00101111 47

# The Bitwise XOR

The XOR operator, ^, combines bits such that if exactly one operand is 1, then the result is 1. Otherwise, the result is zero. The following example shows the effect of the ^. This example also demonstrates a useful attribute of the XOR operation. Notice how the bit pattern of 42 is inverted wherever the second operand has a 1 bit. Wherever the second operand has a 0 bit, the first operand is unchanged. You will find this property useful when performing some types of bit manipulations.

00101010 42

^00001111 15

---------

00100101 37

# Using the Bitwise Logical Operators

The following program demonstrates the bitwise logical operators:

// Demonstrate the bitwise logical operators.

class BitLogic {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String[] binary = {

"0000", "0001", "0010", "0011", "0100", "0101", "0110", "0111",

"1000", "1001", "1010", "1011", "1100", "1101", "1110", "1111"

};

int a = 3; // 0 + 2 + 1 or 0011 in binary

int b = 6; // 4 + 2 + 0 or 0110 in binary

int c = a | b;

int d = a & b;

int e = a ^ b;

int f = (~a & b) | (a & ~b);

int g = ~a & 0x0f;

System.out.println(" a = " + binary[a]);

System.out.println(" b = " + binary[b]);

System.out.println(" a|b = " + binary[c]);

System.out.println(" a&b = " + binary[d]);

System.out.println(" a^b = " + binary[e]);

System.out.println("~a&b|a&~b = " + binary[f]);

System.out.println(" ~a = " + binary[g]);

}

}

In this example, a and b have bit patterns that present all four possibilities for two binary digits: 0-0, 0-1, 1-0, and 1-1. You can see how the | and & operate on each bit by the results in c and d. The values assigned to e and f are the same and illustrate how the ^ works. The string array named binary holds the human-readable, binary representation of the numbers 0 through 15. In this example, the array is indexed to show the binary representation of each result. The array is constructed such that the correct string representation of a binary value n is stored in binary[n]. The value of ~a is ANDed with 0x0f (0000 1111 in binary) in order to reduce its value to less than 16, so it can be printed by use of the binary array.

Here is the output from this program:

a = 0011

b = 0110

a|b = 0111

a&b = 0010

a^b = 0101

~a&b|a&~b = 0101

~a = 1100

# The Left Shift

The left shift operator, <<, shifts all of the bits in a value to the left a specified number of times. It has this general form:

value << num

Here, num specifies the number of positions to left-shift the value in value. That is, the << moves all of the bits in the specified value to the left by the number of bit positions specified by num. For each shift left, the high-order bit is shifted out (and lost), and a zero is brought in on the right. This means that when a left shift is applied to an int operand, bits are lost once they are shifted past bit position 31. If the operand is a long, then bits are lost after bit position 63.

Java’s automatic type promotions produce unexpected results when you are shifting byte and short values. As you know, byte and short values are promoted to int when an expression is evaluated. Furthermore, the result of such an expression is also an int. This means that the outcome of a left shift on a byte or short value will be an int, and the bits shifted left will not be lost until they shift past bit position 31. Furthermore, a negative byte or short value will be sign-extended when it is promoted to int. Thus, the high-order bits will be filled with 1’s. For these reasons, to perform a left shift on a byte or short implies that you must discard the high-order bytes of the int result. For example, if you left-shift a byte value, that value will first be promoted to int and then shifted. This means that you must discard the top three bytes of the result if what you want is the result of a shifted byte value. The easiest way to do this is to simply cast the result back into a byte. The following program demonstrates this concept:

// Left shifting a byte value.

class ByteShift {

public static void main(String[] args) {

byte a = 64, b;

int i;

i = a << 2;

b = (byte) (a << 2);

System.out.println("Original value of a: " + a);

System.out.println("i and b: " + i + " " + b);

}

}

The output generated by this program is shown here:

Original value of a: 64

i and b: 256 0

Since a is promoted to int for the purposes of evaluation, left-shifting the value 64 (0100 0000) twice results in i containing the value 256 (1 0000 0000). However, the value in b contains 0 because after the shift, the low-order byte is now zero. Its only 1 bit has been shifted out.

Since each left shift has the effect of doubling the original value, programmers frequently use this fact as an efficient alternative to multiplying by 2. But you need to watch out. If you shift a 1 bit into the high-order position (bit 31 or 63), the value will become negative. The following program illustrates this point:

// Left shifting as a quick way to multiply by 2.

class MultByTwo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int i;

int num = 0xFFFFFFE;

for (i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

num = num << 1;

System.out.println(num);

}

}

}

The program generates the following output:

536870908

1073741816

2147483632

-32

The starting value was carefully chosen so that after being shifted left 4 bit positions, it would produce –32. As you can see, when a 1 bit is shifted into bit 31, the number is interpreted as negative.

# The Right Shift

The right shift operator, >>, shifts all of the bits in a value to the right a specified number of times. Its general form is shown here:

value >> num

Here, num specifies the number of positions to right-shift the value in value. That is, the >> moves all of the bits in the specified value to the right the number of bit positions specified by num.

The following code fragment shifts the value 32 to the right by two positions, resulting in a being set to 8:

int a = 32;

a = a >> 2; // a now contains 8

When a value has bits that are “shifted off,” those bits are lost. For example, the next code fragment shifts the value 35 to the right two positions, which causes the two low-order bits to be lost, resulting again in a being set to 8:

int a = 35;

a = a >> 2; // a now contains 8

Looking at the same operation in binary shows more clearly how this happens:

00100011 35

>>2

00001000 8

Each time you shift a value to the right, it divides that value by two—and discards any remainder. In some cases, you can take advantage of this for high-performance integer division by 2.

When you are shifting right, the top (leftmost) bits exposed by the right shift are filled in with the previous contents of the top bit. This is called sign extension and serves to preserve the sign of negative numbers when you shift them right. For example, –8 >> 1 is –4, which, in binary, is

11111000 -8

>>1

11111100 -4

It is interesting to note that if you shift –1 right, the result always remains –1, since sign extension keeps bringing in more ones in the high-order bits.

Sometimes it is not desirable to sign-extend values when you are shifting them to the right. For example, the following program converts a byte value to its hexadecimal string representation. Notice that the shifted value is masked by ANDing it with 0x0f to discard any sign-extended bits so that the value can be used as an index into the array of hexadecimal characters.

// Masking sign extension.

class HexByte {

static public void main(String[] args) {

char[] hex = {

'0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7',

'8', '9', 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f'

};

byte b = (byte) 0xf1;

System.out.println("b = 0x" + hex[(b >> 4) & 0x0f] + hex[b & 0x0f]);

}

}

Here is the output of this program:

b = 0xf1

# The Unsigned Right Shift

As you have just seen, the >> operator automatically fills the high-order bit with its previous contents each time a shift occurs. This preserves the sign of the value. However, sometimes this is undesirable. For example, if you are shifting something that does not represent a numeric value, you may not want sign extension to take place. This situation is common when you are working with pixel-based values and graphics. In these cases, you will generally want to shift a zero into the high-order bit no matter what its initial value was. This is known as an unsigned shift. To accomplish this, you will use Java’s unsigned, shift-right operator, >>>, which always shifts zeros into the high-order bit.

The following code fragment demonstrates the >>>. Here, a is set to –1, which sets all 32 bits to 1 in binary. This value is then shifted right 24 bits, filling the top 24 bits with zeros, ignoring normal sign extension. This sets a to 255.

int a = -1;

a = a >>> 24;

Here is the same operation in binary form to further illustrate what is happening:

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 -1 in binary as an int

>>>24

00000000 00000000 00000000 11111111 255 in binary as an int

The >>> operator is often not as useful as you might like, since it is only meaningful for 32- and 64-bit values. Remember, smaller values are automatically promoted to int in expressions. This means that sign extension occurs and that the shift will take place on a 32-bit rather than on an 8- or 16-bit value. That is, one might expect an unsigned right shift on a byte value to zero-fill beginning at bit 7. But this is not the case, since it is a 32-bit value that is actually being shifted. The following program demonstrates this effect:

// Unsigned shifting a byte value.

class ByteUShift {

static public void main(String[] args) {

char[] hex = {

'0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7',

'8', '9', 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f'

};

byte b = (byte) 0xf1;

byte c = (byte) (b >> 4);

byte d = (byte) (b >>> 4);

byte e = (byte) ((b & 0xff) >> 4);

System.out.println(" b = 0x"

+ hex[(b >> 4) & 0x0f] + hex[b & 0x0f]);

System.out.println(" b >> 4 = 0x"

+ hex[(c >> 4) & 0x0f] + hex[c & 0x0f]);

System.out.println(" b >>> 4 = 0x"

+ hex[(d >> 4) & 0x0f] + hex[d & 0x0f]);

System.out.println("(b & 0xff) >> 4 = 0x"

+ hex[(e >> 4) & 0x0f] + hex[e & 0x0f]);

}

}

The following output of this program shows how the >>> operator appears to do nothing when dealing with bytes. The variable b is set to an arbitrary negative byte value for this demonstration. Then c is assigned the byte value of b shifted right by four, which is 0xff because of the expected sign extension. Then d is assigned the byte value of b unsigned shifted right by four, which you might have expected to be 0x0f but is actually 0xff because of the sign extension that happened when b was promoted to int before the shift. The last expression sets e to the byte value of b masked to 8 bits using the AND operator, then shifted right by four, which produces the expected value of 0x0f. Notice that the unsigned shift right operator was not used for d, since the state of the sign bit after the AND was known.

b = 0xfl

b >> 4 = 0xff

b >>> 4 = 0xff

(b & 0xff) >> 4 = 0x0f

# Bitwise Operator Compound Assignments

All of the binary bitwise operators have a compound form similar to that of the algebraic operators, which combines the assignment with the bitwise operation. For example, the following two statements, which shift the value in a right by four bits, are equivalent:

a = a >> 4;

a >>= 4;

Likewise, the following two statements, which result in a being assigned the bitwise expression a OR b, are equivalent:

a = a | b;

a |= b;

The following program creates a few integer variables and then uses compound bitwise operator assignments to manipulate the variables:

class OpBitEquals {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c = 3;

a |= 4;

b >>= 1;

c <<= 1;

a ^= c;

System.out.println("a = " + a);

System.out.println("b = " + b);

System.out.println("c = " + c);

}

}

The output of this program is shown here:

a = 2

b = 1

c = 6

# Relational Operators

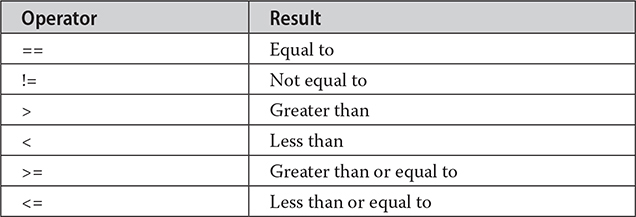

The relational operators determine the relationship that one operand has to the other. Specifically, they determine equality and ordering. The relational operators are shown here:

The outcome of these operations is a boolean value. The relational operators are most frequently used in the expressions that control the if statement and the various loop statements.

Any type in Java, including integers, floating-point numbers, characters, and Booleans can be compared using the equality test, ==, and the inequality test, !=. Notice that in Java equality is denoted with two equal signs, not one. (Remember: a single equal sign is the assignment operator.) Only numeric types can be compared using the ordering operators. That is, only integer, floating-point, and character operands may be compared to see which is greater or less than the other.

As stated, the result produced by a relational operator is a boolean value. For example, the following code fragment is perfectly valid:

int a = 4;

int b = 1;

boolean c = a < b;

In this case, the result of a<b (which is false) is stored in c.

If you are coming from a C/C++ background, please note the following. In C/C++, these types of statements are very common:

int done;

//...

if(!done)... // Valid in C/C++

if(done)... // but not in Java.

In Java, these statements must be written like this:

if(done == 0)... // This is Java-style

if(done != 0)...

The reason is that Java does not define true and false in the same way as C/C++. In C/C++, true is any nonzero value and false is zero. In Java, true and false are nonnumeric values that do not relate to zero or nonzero. Therefore, to test for zero or nonzero, you must explicitly employ one or more of the relational operators.

# Boolean Logical Operators

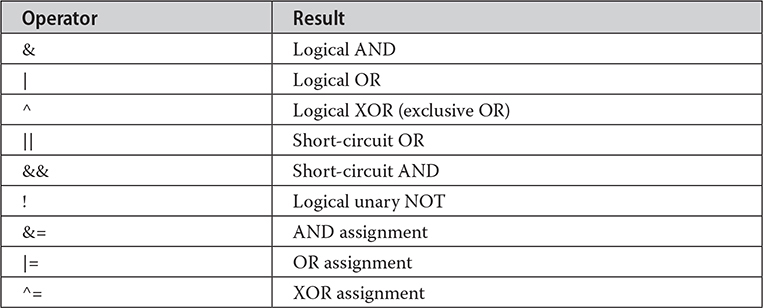

The Boolean logical operators shown here operate only on boolean operands. All of the binary logical operators combine two boolean values to form a resultant boolean value.

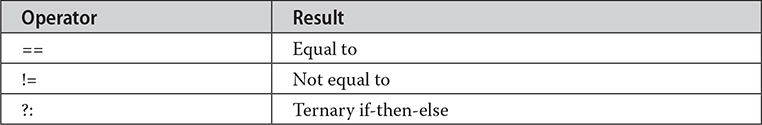

The logical Boolean operators, &, |, and ^, operate on boolean values in the same way that they operate on the bits of an integer. The logical ! operator inverts the Boolean state: !true == false and !false == true. The following table shows the effect of each logical operation:

Here is a program that is almost the same as the BitLogic example shown earlier, but it operates on boolean logical values instead of binary bits:

// Demonstrate the boolean logical operators.

class BoolLogic {

public static void main(String[] args) {

boolean a = true;

boolean b = false;

boolean c = a | b;

boolean d = a & b;

boolean e = a ^ b;

boolean f = (!a & b) | (a & !b);

boolean g = !a;

System.out.println(" a = " + a);

System.out.println(" b = " + b);

System.out.println(" a|b = " + c);

System.out.println(" a&b = " + d);

System.out.println(" a^b = " + e);

System.out.println("!a&b|a&!b = " + f);

System.out.println(" !a = " + g);

}

}

After running this program, you will see that the same logical rules apply to boolean values as they did to bits. As you can see from the following output, the string representation of a Java boolean value is one of the literal values true or false:

a = true

b = false

a|b = true

a&b = false

a^b = true

!a&b|a&!b = true

!a = false

# Short-Circuit Logical Operators

Java provides two interesting Boolean operators not found in some other computer languages. These are secondary versions of the Boolean AND and OR operators, and are commonly known as short-circuit logical operators. As you can see from the preceding table, the OR operator results in true when A is true, no matter what B is. Similarly, the AND operator results in false when A is false, no matter what B is. If you use the || and && forms rather than the | and & forms of these operators, Java will not bother to evaluate the right-hand operand when the outcome of the expression can be determined by the left operand alone. This is very useful when the right-hand operand depends on the value of the left one in order to function properly. For example, the following code fragment shows how you can take advantage of short-circuit logical evaluation to be sure that a division operation will be valid before evaluating it:

if (denom != 0 && num / denom > 10)

Since the short-circuit form of AND (&&) is used, there is no risk of causing a run-time exception when denom is zero. If this line of code were written using the single & version of AND, both sides would be evaluated, causing a run-time exception when denom is zero.

It is standard practice to use the short-circuit forms of AND and OR in cases involving Boolean logic, leaving the single-character versions exclusively for bitwise operations. However, there are exceptions to this rule. For example, consider the following statement:

if(c==1 & e++ < 100) d = 100;

Here, using a single & ensures that the increment operation will be applied to e whether c is equal to 1 or not.

NOTE The formal specification for Java refers to the short-circuit operators as the conditional-and and the conditional-or.

# The Assignment Operator

You have been using the assignment operator since Chapter 2. Now it is time to take a formal look at it. The assignment operator is the single equal sign, =. The assignment operator works in Java much as it does in any other computer language. It has this general form:

var = expression;

Here, the type of var must be compatible with the type of expression.

The assignment operator does have one interesting attribute that you may not be familiar with: it allows you to create a chain of assignments. For example, consider this fragment:

int x, y, z;

x = y = z = 100; // set x, y, and z to 100

This fragment sets the variables x, y, and z to 100 using a single statement. This works because the = is an operator that yields the value of the right-hand expression. Thus, the value of z = 100 is 100, which is then assigned to y, which in turn is assigned to x. Using a “chain of assignment” is an easy way to set a group of variables to a common value.

# The ? Operator

Java includes a special ternary (three-way) operator that can replace certain types of if-then-else statements. This operator is the ?. It can seem somewhat confusing at first, but the ? can be used very effectively once mastered. The ? has this general form:

expression1 ? expression2 : expression3

Here, expression1 can be any expression that evaluates to a boolean value. If expression1 is true, then expression2 is evaluated; otherwise, expression3 is evaluated. The result of the ? operation is that of the expression evaluated. Both expression2 and expression3 are required to return the same (or compatible) type, which can’t be void.

Here is an example of the way that the ? is employed:

ratio = denom == 0 ? 0 : num / denom;

When Java evaluates this assignment expression, it first looks at the expression to the left of the question mark. If denom equals zero, then the expression between the question mark and the colon is evaluated and used as the value of the entire ? expression. If denom does not equal zero, then the expression after the colon is evaluated and used for the value of the entire ? expression. The result produced by the ? operator is then assigned to ratio.

Here is a program that demonstrates the ? operator. It uses it to obtain the absolute value of a variable.

// Demonstrate ?.

class Ternary {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int i, k;

i = 10;

k = i < 0 ? -i : i; // get absolute value of i

System.out.print("Absolute value of ");

System.out.println(i + " is " + k);

i = -10;

k = i < 0 ? -i : i; // get absolute value of i

System.out.print("Absolute value of ");

System.out.println(i + " is " + k);

}

}

The output generated by the program is shown here:

Absolute value of 10 is 10

Absolute value of -10 is 10

# Operator Precedence

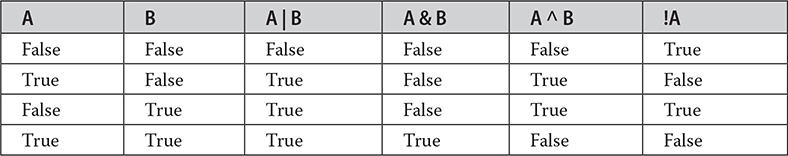

Table 4-1 shows the order of precedence for Java operators, from highest to lowest. Operators in the same row are equal in precedence. In binary operations, the order of evaluation is left to right (except for assignment, which evaluates right to left). Although they are technically separators, the [ ], ( ), and . can also act like operators. In that capacity, they would have the highest precedence. Also, notice the arrow operator (->). It is used in lambda expressions.

Table 4-1 The Precedence of the Java Operators

# Using Parentheses

Parentheses raise the precedence of the operations that are inside them. This is often necessary to obtain the result you desire. For example, consider the following expression:

a >> b + 3

This expression first adds 3 to b and then shifts a right by that result. That is, this expression can be rewritten using redundant parentheses like this:

a >> (b + 3)

However, if you want to first shift a right by b positions and then add 3 to that result, you will need to parenthesize the expression like this:

(a >> b) + 3

In addition to altering the normal precedence of an operator, parentheses can sometimes be used to help clarify the meaning of an expression. For anyone reading your code, a complicated expression can be difficult to understand. Adding redundant but clarifying parentheses to complex expressions can help prevent confusion later. For example, which of the following expressions is easier to read?

a | 4 + c >> b & 7

(a | (((4 + c) >> b) & 7))

One other point: parentheses (redundant or not) do not degrade the performance of your program. Therefore, adding parentheses to reduce ambiguity does not negatively affect your program.